Also by Joel Richard Paul

Unlikely Allies: How a Merchant, a Playwright, and a Spy Saved the American Revolution

Without Precedent: Chief Justice John Marshall and His Times

RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2022 by Joel Richard Paul

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

Riverhead and the R colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Paul, Joel Richard, author.

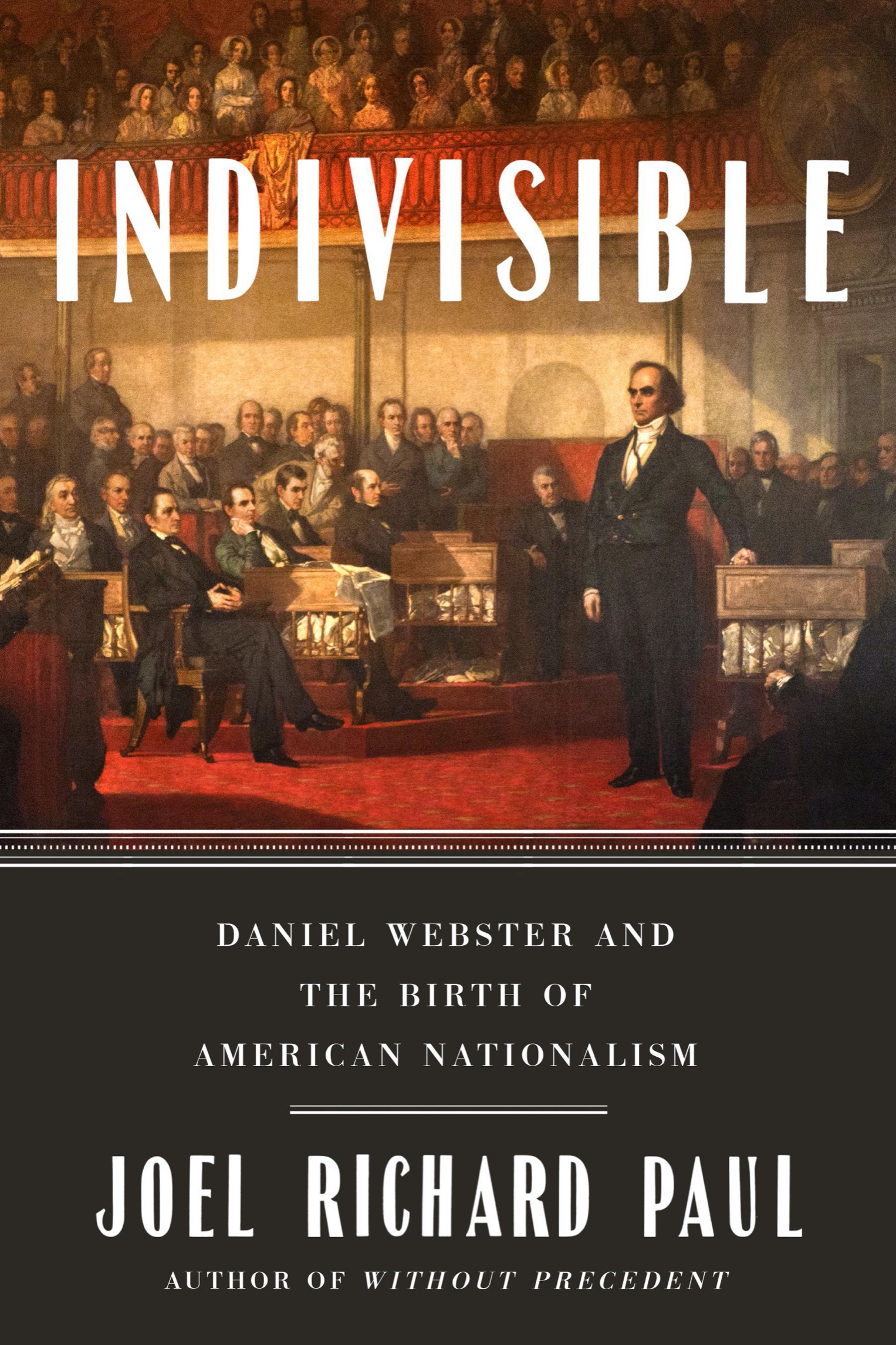

Title: Indivisible : Daniel Webster and the birth of American nationalism / Joel Richard Paul.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2022003812 (print) | LCCN 2022003813 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593189047 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593189061 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: NationalismUnited States. | United StatesPolitics and government17831865. | Webster, Daniel, 17821852.

Classification: LCC E302.1 P38 2022 (print) | LCC E302.1 (ebook) | DDC 973.5092dc23/eng/20220216

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022003812

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022003813

Cover design: Tyriq Moore

Cover art: Websters Reply to Haynes (oil on canvas, 1851), George Peter Alexander Healy, Boston, Massachusetts / Courtesy of the Boston Art Commission

Book design by Cassandra Garruzzo Mueller, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

pid_prh_6.0_141524367_c0_r0

For Jane Shulman, who dared me

Contents

Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable.

Daniel Webster

Introduction

In the beginning we were many, not one: a fractious scrabble of European immigrants, enslaved Africans, and apprehensive Native Americans. Americans were strangers in a wilderness. We were not united in rebellion against a foreign monarch. Most Americans either opposed the revolution or were undecided. We were not one nation, and the least self-evident truth in our Declaration of Independence was the words United States. It was a convenient fiction. How that fiction became reality is the subject of this book.

The political scientist Benedict Anderson described a nation as an imagined community where strangers recognize each other as somehow related and distinct from others whether by geography, language, culture, or race. Nationalism, in its broadest sense, is a matter of perception and a measure of our loyalty to our country, our allegiance to its laws and form of government, our willingness to make sacrifices to support it, and our sense of a common destinythe affinity we feel for each other as citizens.

Citizens derive a sense of security from belonging to a community defined by nationalism. National identity confers a moral right, if not quite a legal right, to self-determination, and modern states gain legitimacy from nationalist aspirations. But when nationalism ripens into an ideology it quickly sours. Nationalist ideologies often manifest themselves as expressions of racial, ethnic, or religious superiority. Nationalist ideologies often lead to intolerance, nativism, and calls for racial purity and genocide. The French philosopher and nineteenth-century historian Ernest Renan argued that race, religion, ethnicity, and language were inadequate bases for establishing a nation, and that any great nation should have a diversity of races, faiths, and ethnicities. To build a nation, Renan explained, it is necessary not merely that people remember a glorious past, but also that they forget what once divided them.

Before the American Revolution, North Americans saw themselves as colonists of their respective colonies. Many proudly identified themselves as British subjects. It would take more than a generation to scrub clean their Britishness. Teatime was, for many, a ritual that expressed both their affinity for Britain and their class. Southern planters sent their sons to the finest British universities. It was British culture that civilized them and set them apart from African slaves and the native inhabitants of North America. Anglophilia was not about nostalgia for life as a British subject; it was an expression of the desire to live like British aristocracy, freed from the drudgery of menial labor. For southern planters, the slave economy made that possible.

For decades after the American Revolution, Americans still self-consciously measured their civilization against Britains. When a European compared Americans favorably with Englishmen, it was widely noted. One Englishman remarked that he had expected to find a people very little civilized, compared with Europeans, but to his astonishment he found that the people were kind and hospitable; that the manners of the higher classes were nearly as polished as could be found in any European country. Another European discovered that Americans were so much better educated, so much better informed, and possess so much better manners... that it is absolutely ludicrous to compare the people of Great Britain with them in those respects. And he marveled that even the servants are far superior to British servants.

Yet Americans suffered from an inferiority complex. The French foreign minister, Charles Maurice de Talleyrand, who took refuge in America from the revolution at home, noticed many Americans who wanted to pass for an Englishman, but never an Englishman who wished to pass for an American.

British nationalism had only recently appeared in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Americans identified with their village, their state, and their region, rather than with the vague theoretical entity known as the United States. Most Americans lived their entire lives in the narrow confines of their state, rarely venturing more than a days journey of about fifty miles in any direction. They had no knowledge of what Americans looked like in other parts of the continent.

When the president of South Carolina College, Dr. Thomas Cooper, was asked by a foreign visitor about his nationality, Cooper replied, If you ask if I am an American, my answer is No, sir, I am a South Carolinian.

The western frontier both unified and divided nineteenth-century Americans. The capacity of this limitless land to absorb millions of settlers opened new opportunities. The West offered Americans a fresh start, freed from the confines of their places of origin. It also opened a rift between the North and South over the displacement of Native Americans and the expansion of slavery.

It was not a foregone conclusion that the Union would form a nation. The centrifugal force of regionalism seemed all too likely to overtake the much weaker pull of nationalism. At the dawn of the nineteenth century Massachusetts author and congressman Fisher Ames worried that the size and diversity of the country, the competing interests of the states, and the demagogic appeal of Jeffersons Republican Party threatened the countrys future. Our country is too big for union, too sordid for patriotism, too democratic for liberty.