Clarion Books

215 Park Avenue South

New York, New York 10003

Copyright 2015 by Catherine Reef

All rights reserved. For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Clarion Books is an imprint of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company.

www.hmhco.com

Map illustrations and front cover image 2015 by Kristine A. Lombardi

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Reef, Catherine.

Noah Webster : man of many words / Catherine Reef.

pages cm

Summary: A biography on Noah Webster, a controversial political activist, the primary shaper of the American language, and author of the Blue-Backed Spellers and the famous dictionary that bears his name. Illustrated with black-and-white archival images.Provided by publisher.

ISBN 978-0-544-12983-2 (hardback)

1. Webster, Noah, 17581843Juvenile literature. 2. LexicographersUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. 3. EducatorsUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. I. Title.

PE64.W5R44 2015

423.092dc23

[B]

2014027803

eISBN 978-0-544-13344-0

v1.0815

For John S. Reef, an astute observer of language

Life is short, and every hour should be employed to good purposes.

Noah Webster

Beginning

noun. that which is first.

N OAH WEBSTER dressed by starlight. Black trousers, black stockings, black coathe wore the stern clothes of a proper New Englander. He was six feet tall, a sturdy oak of a man. Yet he walked gently through the sleeping house. He entered his second-floor study and closed the door just as the first, weak rays of sunlight filtered through the window. The comet that was visible in the night sky, the great comet of 1807, was fading with the dawn.

Webster picked up his spectacles from the circular table that served as his desk and put them on his face. He rubbed his strong hands together, burnishing them against Novembers chill. He had spent many hours in this room, sealed off from the happy sounds of family life. I am not formed for society, he once wrote. The reflections of my own mind were better companions, he said. He irritated others, and he knew it. Even men who had never met Webster called him an incurable lunatic and a spiteful viper.

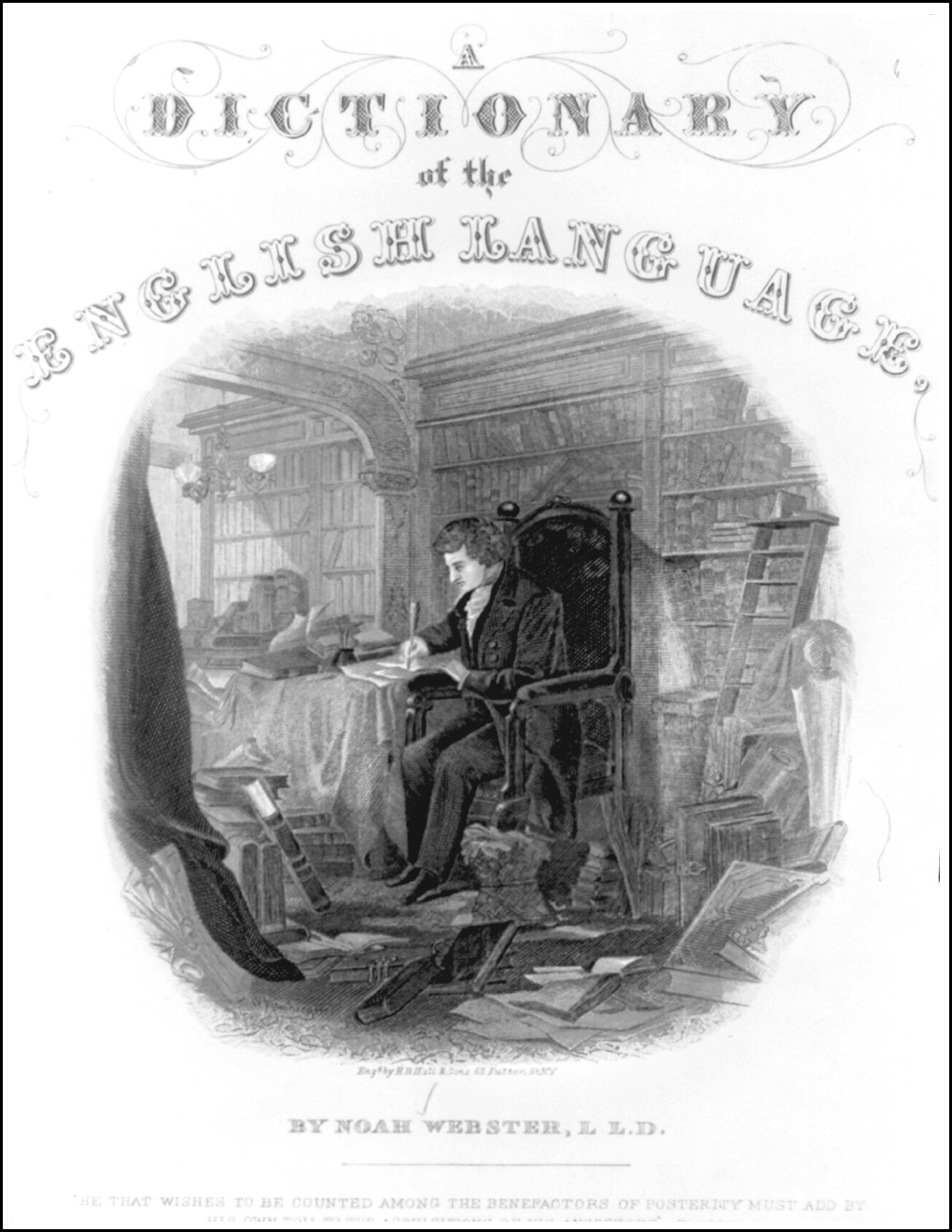

Noah Webster sits at a table, surrounded by his beloved books, in this illustration from an 1879 edition of his dictionary.

What had he done to make these people so upset? He had written. Noah Webster had stirred up controversy by writing books and articles about politics and language.

He had called for a strong federal government when the United States was a brand-new nation unsure of its future. People were deeply divided on the issue, with many insisting that power belonged not to a central government, but to each of the thirteen states. America is an independent empire, and ought to assume a national character, Webster wrote. So long as any individual state has power to defeat the measures of the other twelve, our pretended union is but a name, and our confederation, a cobweb. He urged his fellow citizens to think of themselves as Americans rather than as Virginians, New Yorkers, Pennsylvanians, or residents of his own state, Connecticut.

Webster claimed that English, as spoken and written in the United States, could be a force that brought people together. It is the business of Americans, he stated, to diffuse an uniformity and purity of language,to add superiour dignity to this infant Empire and to human nature. He wanted the language to embrace purely American words, such as skunk and moccasin. He hoped, too, to streamline spelling, to have Americans write wagon and not waggon, and theater rather than theatre. American English was different from British English, Webster insisted, and it ought to be a source of national pride. These notions hardly seem strange today, but when he published his ideas in the 1780s, Webster exposed himself to ridicule. His critics asked one another, What will this oddity of literaturethink of next?

People laughed, but Webster never doubted himself. On this morning, at age forty-nine, he was beginning the greatest project of his life, one his critics called folly. He planned to write a dictionary, the largest and most comprehensive dictionary of the English language ever compiled. It would be an American dictionary, based on his strong opinions, which were the product of many years of thought. He opened a clean notebook, lifted his quill pen, and wrote: A is the first letter of the Alphabet in most of the known languages of the earth....

CHAPTER 1

A Boy Who Dreamed of Books and Words

T HE LETTER A is one kind of beginning; birth is another. Noah Webster, Jr., was born in the West Division of Hartford, Connecticut, in his familys farmhouse, on October 16, 1758. Like his brothers and sisters, Noah was born in the best room, the one that served as a parlor during the day and his parents bedchamber at night. This room was furnished simply, with straight-backed chairs and a four-poster bed. A massive stone fireplace offered heat, and a black Bible sat on the writing desk, ready to be consulted. The Websters sought its guidance for even the simplest duties of daily life.

Noahs mother, Mercy Steele Webster, had a great-great-grandfather who sailed to Plymouth Colony on the Mayflower in search of religious freedom. Like all farm women, Mercy Webster worked hard, making cloth, sewing and mending clothes, cooking and preserving food, gardening, and sweeping out the house. Somehow she had time to school the children in spelling and arithmetic. She read to them and taught them to play the flute. Beauty touched her soul, and she cried easily if she happened on a heartfelt phrase in a book or heard a well-loved melody. She passed along her loves to Noah. As a young man, he would turn to his books and flute whenever he felt low. In his diary he marveled that the sound of a little hollow tube of wood should dispel in a few moments, or at least alleviate, the heaviest cares of life!

Mercy Webster led the family in singing psalms every night. As good colonial parents, the Websters made their home a godly setting, to start the children on the path to salvation. Mercys husband, Noah Webster, Sr., had little formal schooling, but he was a bright man whose mind was open to new ideas. He was a founder of the local First Book Society, an early version of a public library. He served as a church deacon and justice of the peace.

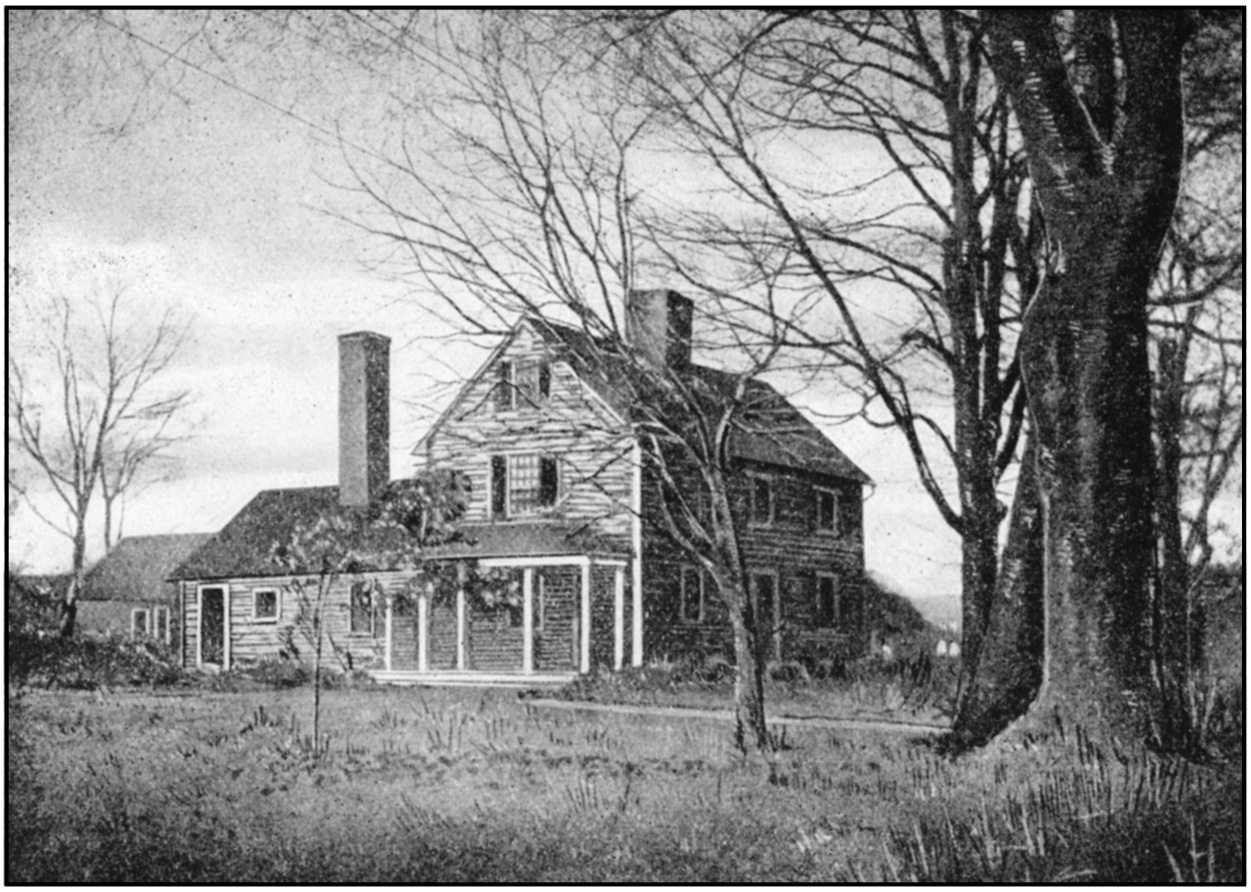

Noah Websters childhood home, shown here in a picture from 1912, was restored in the 1960s and opened as a museum.

Hartford in the 1750s was one of Connecticuts two capitals; New Haven was the other. Hartford was a growing town, where twenty or more shops lined the main street, selling everything from sugar, tea, and flour to gunpowder, nails, and axes. Some merchants were so eager for profits that they built shops on top of Hartfords old burial ground, which had been set aside as a graveyard in 1640. Others moved their businesses closer and closer to the road. In 1758, the year Noah was born, Hartfords leaders halted this inching forward by ordering property owners in the center of town to put in brick sidewalks.