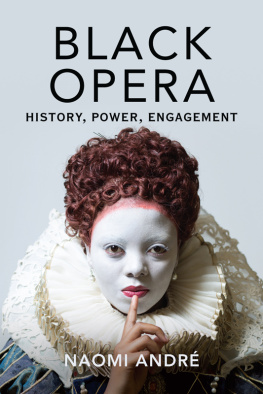

Black Opera

Black Opera

History, Power, Engagement

NAOMI ANDR

Publication of this book is supported by the Manfred Bukofzer Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation.

Portions of have been adapted from Winnie, Opera, and South African Artistic Nationhood, African Studies , no. 1 (2016), 2016 by Taylor & Francis. Reprinted by permission.

2018 by the Board of Trustees

of the University of Illinois

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Andr, Naomi Adele, author.

Title: Black opera: history, power, engagement / Naomi Andr.

Description: Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017056072| ISBN 9780252041921 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252083570 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780252050619 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : Blacks in opera. | Opera.

Classification: LCC ML 1700 . A 53 2018 | DDC 782.1089/96dc23 lc record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017056072

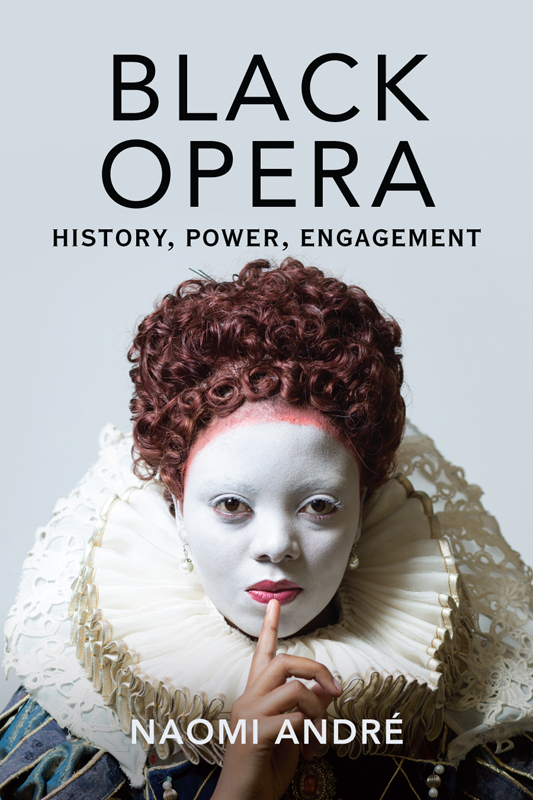

Cover illustration: Courtesy of Cape Town Opera, photographer Bernard Bruwer

Contents

Acknowledgments

This project has benefited from generous support from my home institution, the University of Michigan, and the guidance of many people. I was fortunate to receive funding from the UM African Studies Center (the wonderful African Heritage Initiative), the Institute for Research on Women and Gender, a Humanities Faculty Fellowship, and the LSA Associate Professor Support Fund. I was further aided by additional support from Womens Studies, the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies, and the Residential College. A special thanks goes to the Women of Color in the Academy Project for their writing groups and retreats as well as their warm collegiality.

I have been fortunate to have colleagues and friends who have given me very helpful feedback as I have moved through the process of pulling this project together from many diverse experiences and ideas. I am grateful for the extremely valuable comments I have received from people who have read portions of the manuscript at various stages: Evelyn Asultany, David Burkham, Suzanne Camino, Evan Chambers, William Cheng, Mariah Fink, Jennifer Myers, Marti Newland, Josh Rabinowitz, Kira Thurman, and Michael Uy. Many thanks to Mark Clague and his dynamite seminar on Porgy and Bess (fall 2017) for reading over and commenting on the various stages, including identifying courageous readers who generously gave me critical advice and helped me clarify and strengthen the presentation of my ideas and assembling a wonderful production team (many thanks especially to Jennifer Clark and Julie Gay).

A growing group of scholars who have become friends and supporters over the years in our mutual quest to flesh out sources and shape a historiography of black composers, to practice new formations of intersectional analyses, and to pioneer directions in music scholarship: these dear people include Ellie Hisama, Tammy Kernodle, Karen Bryan, Gwynne Kuhner Brown, Kira Thurman, and Alison Kinney. Thank you for being beacons in the groves of underexplored repertories and populations.

I am fortunate and thankful to belong to a diverse, rich intellectual community in multiple disciplines within the University of Michigan, across the United States, and in South Africa. Most locally in Ann Arbor are Sandra Gunning, Amal Fadlalla, Edie Lewis, Kelly Askew, Cynthia Burton, Terri Conley, Helen Fox, Susan Walton, Beth Genne, Rebecca Schwartz-Bishir, Ruth Tsoffar, Tiana Marquez, Sarah Fenstermaker, Elinor Linn, and Marc Gerstein. More broadly are April James, Nancy Clark, Marnie Schroer, the Callahan family (especially Michael, Susan, and Treana), Donato Somma, and Innocentia Jabulisile Mhlambi. There is a very special group of people who have known me for at least a couple of decades and are particularly marvelous in remembering things about me that help me navigate the sensational as well as the tough times: Caroline Gaither, Rachel Andrews and Kathy Battles, Wendy Giman, and Leone and Ken Litt.

Fueling this project were a few special local hangouts: Zingermans Coffee Company and the Mighty Good Coffee at Arbor Hills. I also want to express happiness for having Piper, Zeus, and Danny as faithful writing companions.

My deep appreciation goes to Don for his care and support in holding things together on the home front and being a thoughtful listening ear. I also want to mention my love and joy for being Safiyas mom and for having her wonderfully earthshaking presence in my life.

Black Opera

Engaged Opera

Throughout this book I present a way of thinking, interpreting, and writing about music in performance that incorporates how race, gender, sexuality, and nation help shape the analysis of opera today. My focus is on how these works, regardless of whether they were written in the distant or recent past, resonate with the issues and experiences of people today: those in the audience and wider contemporary publics. Most musicological analysis, including opera studies, has done its best to reconstruct a viable historical context from what we know of the past to help us understand how we might think about this work in the present. Some of that energy fueled the desire to reconstruct historically informed performance practice, for example, recreating how Mozart might have first seen and heard his operas (such as the instruments used, the ornamentation improvised, and the materials for the costumes and set designs). This book departs from the solitary goal of understanding how music might have had meaning in the past. While the past is relevant to a general understanding, my larger emphasis is on how these operas have meaning for current audiences. By audiences I am referring both to the actual people in the concert hall as well as potential audience members among those who do not attend classical (in the general sense) concerts because such venues seem too elitist or outside of their grasp. I am interested in what audiences today see and the connections they can draw to recent and current historical events; this method of inquiry incorporates the shared lived experiences of everyone involved: the performers and the public. Such an approach that brings together opera in a historical context and focuses on how it resonates in the present day points to a type of analysis I call an engaged musicology .

Black Otello

I start with two true stories about Verdis 1887 opera Otello as it was performed early in the second decade of the twenty-first century. These events provide a context for the impetus of this study. The first happened in the fall of 2012; the second is from the summerfall 2015.

In the fall of 2012 I took one of my black South African colleagues to a performance of Verdis Otello in the Metropolitan Operas Live in HD series. My colleague was a visiting scholar from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, and we were part of a small team embarking on a research project that was examining the current opera scene in South Africa. This colleague was in the middle of a six-month stay here at the University of Michigan, and one of my pleasures was going to live opera performances together at the School of Music, Theatre and Dance at the university, and in Detroit at the Michigan Opera Theatre. The Metropolitan Operas Live in HD broadcasts involved a type of hybrid live experience as we watched the Saturday matinee performance of the Metropolitan Opera in real time, live streaming to a local movie theater.