Contents

Guide

Pages

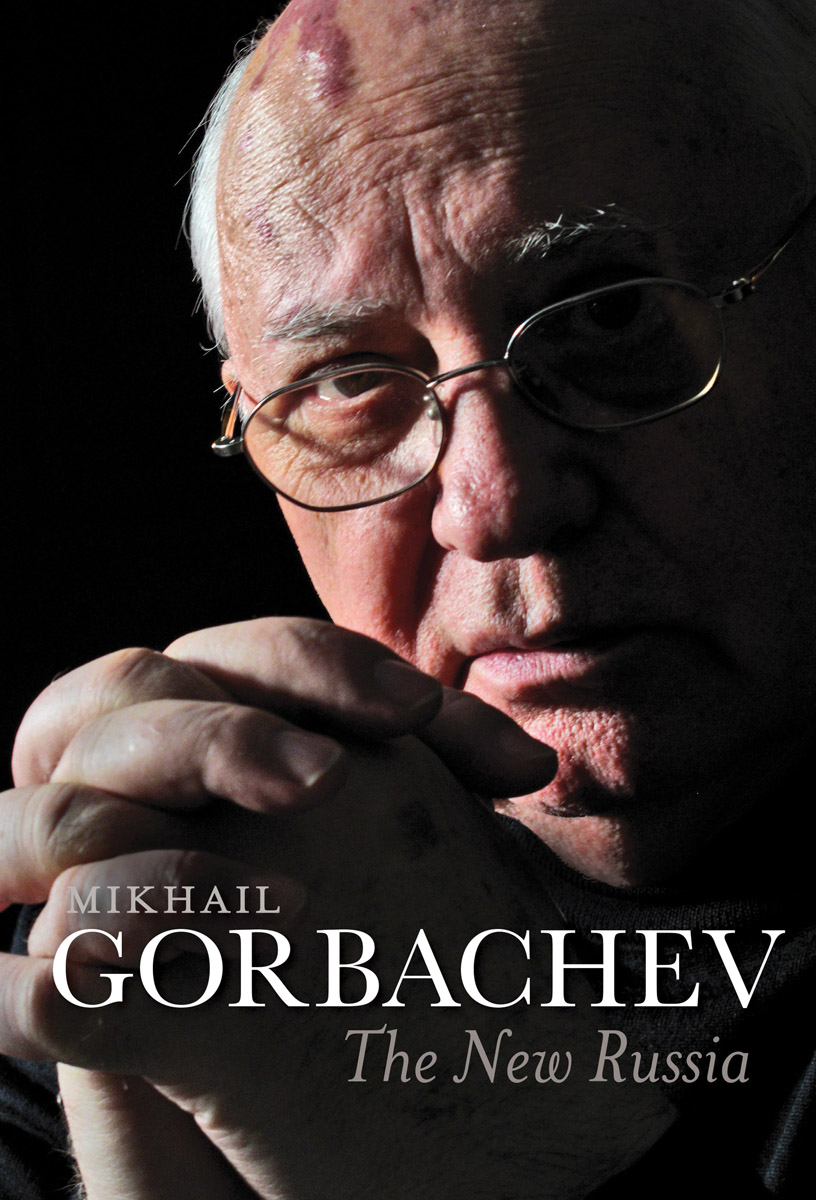

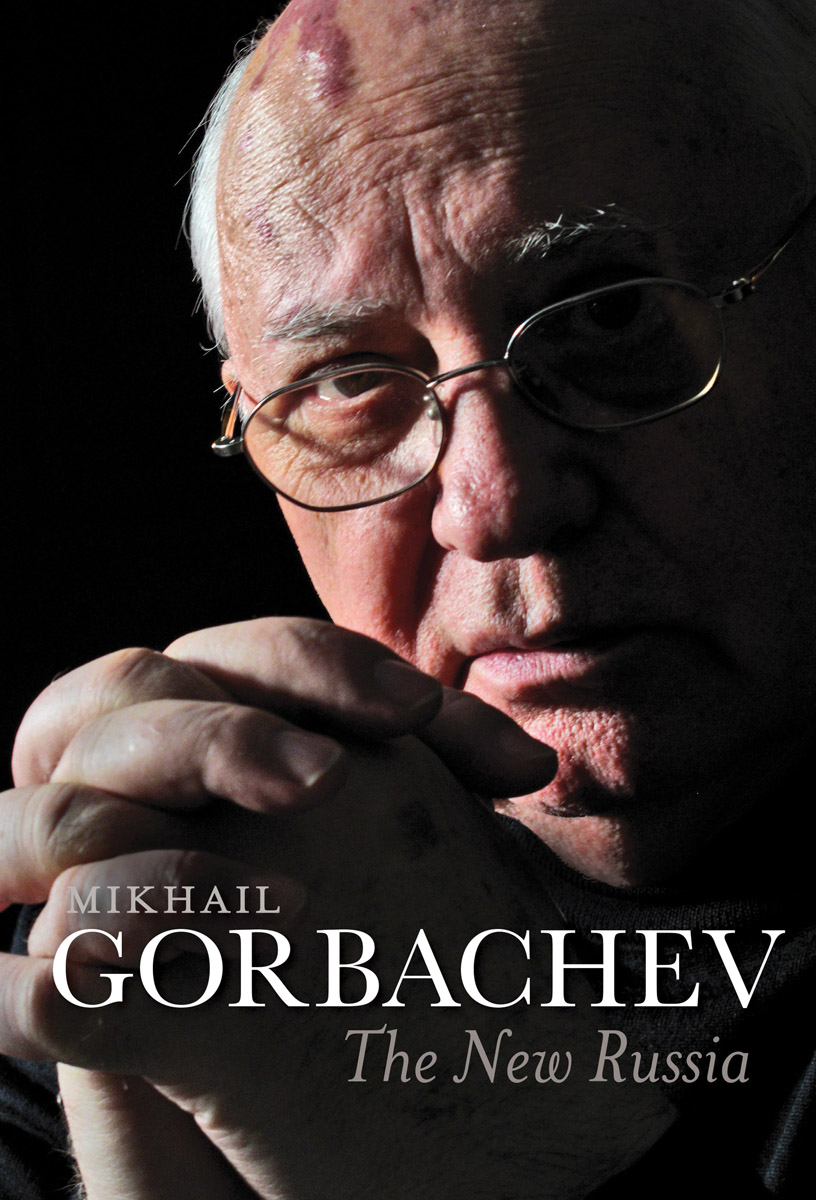

The New Russia

Mikhail Gorbachev

Translated by Arch Tait

polity

First published in Russian as /Posle Kremlya, Mikhail Sergeyevich Gorbachev, 2015 This English edition Polity Press, 2016

All images The Gorbachev Foundation, 2016

Polity Press

65 Bridge Street

Cambridge CB2 1UR, UK

Polity Press

350 Main Street

Malden, MA 02148, USA

All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purpose of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN-13: 978-1-5095-0391-9

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, 1931- author.

Title: The new Russia / Mikhail Gorbachev.

Other titles: Posle Kremlya. English

Description: English edition. | Cambridge, UK : Polity, 2016. | First published in Russian as Posle Kremlya, Moskva : Ves Mir, 2014. | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015042490 (print) | LCCN 2015049601 (ebook) | ISBN 9781509503872

(hardback) | ISBN 9781509503902 (Mobi) | ISBN 9781509503919 (Epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, 1931- | Gorbachev, Mikhail Sergeevich, 1931---Political and social views. | Presidents--Soviet Union--Biography. | Ex-presidents--Soviet Union--Biography. | Kommunisticheska, a parti, a Sovetskogo So, uza--Biography. | Perestroika--History. | Soviet Union--Politics and government--1985-1991. | Russia (Federation)--Politics and government--1991- | Social change--Russia (Federation)--History. | Political culture--Russia (Federation)--History. | BISAC: POLITICAL SCIENCE / International Relations / General.

Classification: LCC DK290.3.G67 G67213 2016 (print) | LCC DK290.3.G67 (ebook) | DDC 947.085/4092--dc23

LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015042490

The publisher has used its best endeavours to ensure that the URLs for external websites referred to in this book are correct and active at the time of going to press. However, the publisher has no responsibility for the websites and can make no guarantee that a site will remain live or that the content is or will remain appropriate.

Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition.

For further information on Polity, visit our website: politybooks.com

Preface: Perestroika and the Future

This is a book about the relevance of the past. Reflecting on what happened to Russia and Russians at the end of the last and beginning of this century, and what awaits Russia in the future, you inevitably come back to the years of Perestroika. Today, more than two decades separate us from that time, but it is probably still too early to attempt any final assessment. Chou En-Lai is said to have replied to President Richard Nixons question of how he assessed the French Revolution: It is too soon to judge. He may have been right, yet much can already be seen more clearly.

Today there is again a great sense in Russia of a need for change. Society cannot feel satisfied with the current situation. The attempts at reform undertaken in the past two decades have not been seen through to the end. Of course, we cannot say there have been no changes in peoples lives, but many of their hopes have been disappointed and there has been no genuine renewal of life in the interests of the majority of our citizens.

A dead-end political situation, economic stagnation, a build-up of unresolved social problems, violation of the rights and dignity of citizens: all this is only too reminiscent of the state of the country before Perestroika, and people are not happy. Although it has proved possible to temporarily stifle the protest movement that began in December 2011, it is impossible to suppose that those presently in power are unaware of citizens discontent.

It is no longer possible to say, as we have been doing for very many years, that Russia needs time, that changes of this magnitude cannot be rushed. That is perfectly true, and I have often used that argument in my speeches and in conversations with foreign politicians. Now, however, the process of transition has been going on for two and a half decades, and with every year that passes the argument becomes less convincing.

How should we respond to this state of affairs? What should we do? I am concerned that many are looking for the answer in the wrong direction. They believe it can be found by abandoning the democratic achievements of the Perestroika period. There are attempts to rehabilitate authoritarianism and return to its techniques of administrative pressure and tightening the screws. They extol conservatism and try to turn it into a state ideology, claiming that is more in tune with our traditions and Russias cultural code.

In President Putins speeches we hear him quoting conservative Russian philosophers like Ivan Ilyin and Konstantin Leontiev. They cannot be detached from the times in which they lived and contemplated, and we are living in the twenty-first century, a century of new technologies and new challenges. Conservative ideology has no answer to these. Traditional, conservative values do, along with others, have their place in society. But where have conservative policies taken us in the history of Russia? They have led, as a rule, to stagnation followed by upheaval. Sometimes the years of stagnation have been relatively prosperous, living off reforms carried through earlier and favourable external factors. Sooner or later, however, that energy runs out, the external factors change.

The present Russian regime need have no delusions that conservatism is a panacea for our problems, lulling themselves with the belief that for the sake of peace and quiet people will agree to put up with stagnation. They are wrong. I am increasingly convinced that all they are doing is playing for time, clinging to power for its own sake, clutching at the benefits that a minority is able to extract from the current state of affairs.

But people are not blind and their patience is not limitless. They have demonstrated in protest on Bolotnaya Square and Sakharov Prospekt, demanding change. If there is none, the protests will not just be repeated but will become more radical. This would be dangerous and must be avoided. Russia really does not need more turmoil; she needs change, change that opens the way to a genuine renewal of society and improvement in peoples lives.

The road will not be straightforward, but in the Perestroika years we did what was most difficult by breaking free of the totalitarian past. At that time and later, we were to live through many moments of high drama, but I am certain that was not in vain.

My message to Russia and the world is a message of hope.

Trying To Bury Me

On 8 August 2013 the newswires of many agencies and media reported: Mikhail Gorbachev, the first and last Soviet president, has died, according to a message on the Twitter account of RIA Novosti. He was 82 years old. There is as yet no official confirmation of this information.

The phone rang. It was Andrey Karplyuk. He reports now for the ITAR-TASS news agency but used to work for Interfax, and we have kept in touch for several years now.

Mikhail Sergeyevich, I phone you quite often, but this call is not altogether routine. I sensed he was smiling. What I mean is, the reason is a bit unusual.