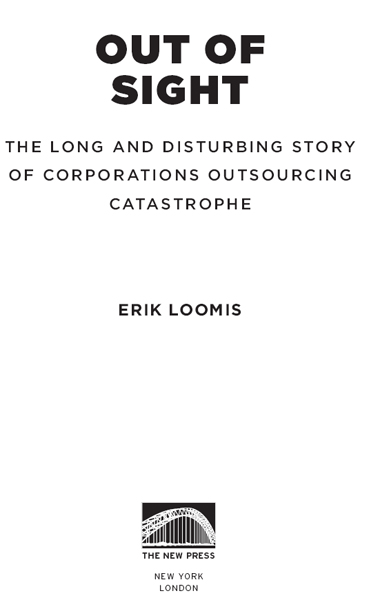

OUT OF SIGHT

For Katie

2015 by Erik Loomis

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2015

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Loomis, Erik.

Out of sight : the long and disturbing story of corporations outsourcing catastrophe / Erik Loomis.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-62097-077-5 (e-book) 1. Contracting out--Moral and ethical aspects--United States. 2. Manufactures--Contracting out--United States. 3. Industrial relations--United States. 4. Labor--United States. 5. Labor--Developing countries. 6. Industrial safety--Developing countries. 7. Employee rights--Developing countries. I. Title.

HD2368.U6L66 2015

338.6--dc23

2014039758

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by Bookbright Media

This book was set in Minion Pro and Gotham

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

There are so many people to thank when writing any book. I want to express my appreciation for my editor Jed Bickman and the rest of the staff at The New Press for their great help and support in putting together this project. They have been nothing but professional throughout this process, and its an honor to be published by a press that has distributed so many seminal books that have created positive social change.

This book synthesizes a tremendous amount of literature, both scholarly and journalistic. I hold everyone whose work I cited in this book in great esteem. Thank you for your hard work and dedication to your craft of gathering the information we need to build a more just society.

I would very much like to thank my colleagues in the history department at the University of Rhode Island for their support as well: Timothy George, Robert Widell, Bridget Buxton, Alan Verskin, Rosie Pegueros, Rae Ferguson, Miriam Reumann, James Ward, Eve Sterne, Rod Mather, Joelle Rollo-Koster, Michael Honhart, and Marie Schwartz. It is rare for a historian to have the opportunity to bridge the past and present in such a public forum, and I have received nothing but support from my colleagues in this endeavor.

A very special thanks goes to my colleagues at the blog Lawyers, Guns, & Money for allowing me to work out these ideas in our collective public forum: Robert Farley, Scott Lemieux, David Watkins, Paul Campos, David Brockington, Bethany Spencer, David Noon, Steven Attewell, and Scott Eric Kaufman. I also thank LGMs commenting community for its support of my good ideas and its pushback against my bad ideas. In an era where the nastiness of anonymous Internet commenting threatens the entire enterprise of online communities, LGM has proven an exception.

My dissertation adviser and longtime writing mentor Virginia Scharff also deserves a great deal of credit for this project. Her work on my writing over many years gave me the tools to articulate the thoughts in this project.

I have also received a tremendous amount of support over the past several years from the Internets labor and left-leaning communities, including journalists, labor organizers, and historians. This has included encouragement for my writing, the opening of venues for my work, and support in hard times. There are really too many people to thank, but I want specifically to mention Sarah Jaffe for her constant advocacy for my work and her excellent editing of many articles of mine she commissioned; Mike Elk for welcoming me into the labor journalist community; and Brett Banditelli for his knowledge, Class War Kitteh, and labor history tours of Pennsylvania. Ryan Edgington provided insightful comments on a draft of chapter four that were extremely helpful.

A debt I cannot repay is that I owe Lindsay Beyerstein, who began the process that led to this book.

My family has always been incredibly supportive of all my endeavors. Many thanks and much love to my brother, Daryl Loomis; my sister and brother-in-law, Kris and Carlie DiOrio; and my in-laws Bill and Cassie McIntyre, Kevin and Claire McIntyre, Sean and Megan McIntyre, Bill McIntyre, and Siobhan and Mike Bubel and all their children. Most of these people were exposed to cranky author syndrome for the first time and took it in good humor.

As for my parents, their support and pride in me could not be matched by anyone in the world. Ray and Linda Loomis always sacrificed to make sure I had what I needed to go from the timber mill town of Springfield, Oregon, to the halls of academia. Better parents would be hard to imagine.

Finally and as always, my wife, Kathleen McIntyre, has given me more love and devotion than I can possibly deserve.

Now capital has wings... capital can deal with twenty labor markets at once and pick and choose among them. Labor is fixed in one place. So power has shifted.

Robert Johnson, New York financier, circa 1993

O n the morning of March 25, 1911, around five hundred workers started another day at the Triangle Shirtwaist Company in New York City, as they did six days a week. Mostly young Jewish and Italian immigrant women, the workers could not have guessed that many of them would die that afternoon. Max Blanck and Isaac Harris owned the factory, making shirtwaistsa popular garment for women of the eraon the eighth, ninth, and tenth floors of the Asch Building, just off Washington Square Park in Greenwich Village. Like other apparel manufacturers, Blanck and Harris did not market clothing. Instead, they took orders from designers and department stores under contracts that allowed sellers maximum flexibility in a rapidly changing fashion world without responsibility for the workers. So long as Blanck and Harris made the clothes for the agreed cost, the stores asked no questions.

Clothing sweatshops could burst in flame at any time. Bosses crammed workers into tiny spaces and piled flammable cloth

We think we remember Triangle today for the unique horror of its massive death count. But in fact we remember it because it spawned national outrage that led to long-term change in workplace safety. The fire itself was not an aberration for the time. Millions of American workers in the early twentieth century risked their lives daily by going to work. Coal miners died by the thousands from mine explosions and cave-ins. The Cherry Mine fire in Illinois in 1909 killed 259 workers. The Darr Mine explosion in Pennsylvania in 1907 killed 239. Meatpackers perished from electrocutions, meat hooks knocking them in the head, and tuberculosis. Falling trees crushed loggers, and timber mill workers lost limbs and lives after getting caught in saws and machines. Just a few months before the Triangle Fire, on November 26, 1910, a textile factory in Newark, New Jersey, caught fire and killed twenty-six workers. Each incident made newspaper headlines, but none of these disasters spawned national

Next page