HOW TO READ A PROTEST

THE ART OF ORGANIZING AND RESISTANCE

L.A. KAUFFMAN

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu.

University of California Press

Oakland, California

2018 by L.A. Kauffman

Designer: Lia Tjandra

Compositor: Lia Tjandra and IDS Infotech Limited

Printer: Maple Press

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Kauffman, L.A., author.

Title: How to read a protest : the art of organizing and resistance / L.A. Kauffman.

Description: Oakland, California : University of California Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2018019777 (print) | LCCN 2018024177 (ebook) | ISBN 9780520972209 (e-book) | ISBN 9780520301528 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH : Protest movementsUnited StatesHistory20th century. | Protest movementsUnited StatesHistory21st century.

Classification: LCC HM 883 (ebook) | LCC HM 883 . K 38 2018 (print) | DDC 303.48/409730904dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018019777

Manufactured in the United States of America

26 25 24 23 22 21 20 19 18

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

To N. and D.

CONTENTS

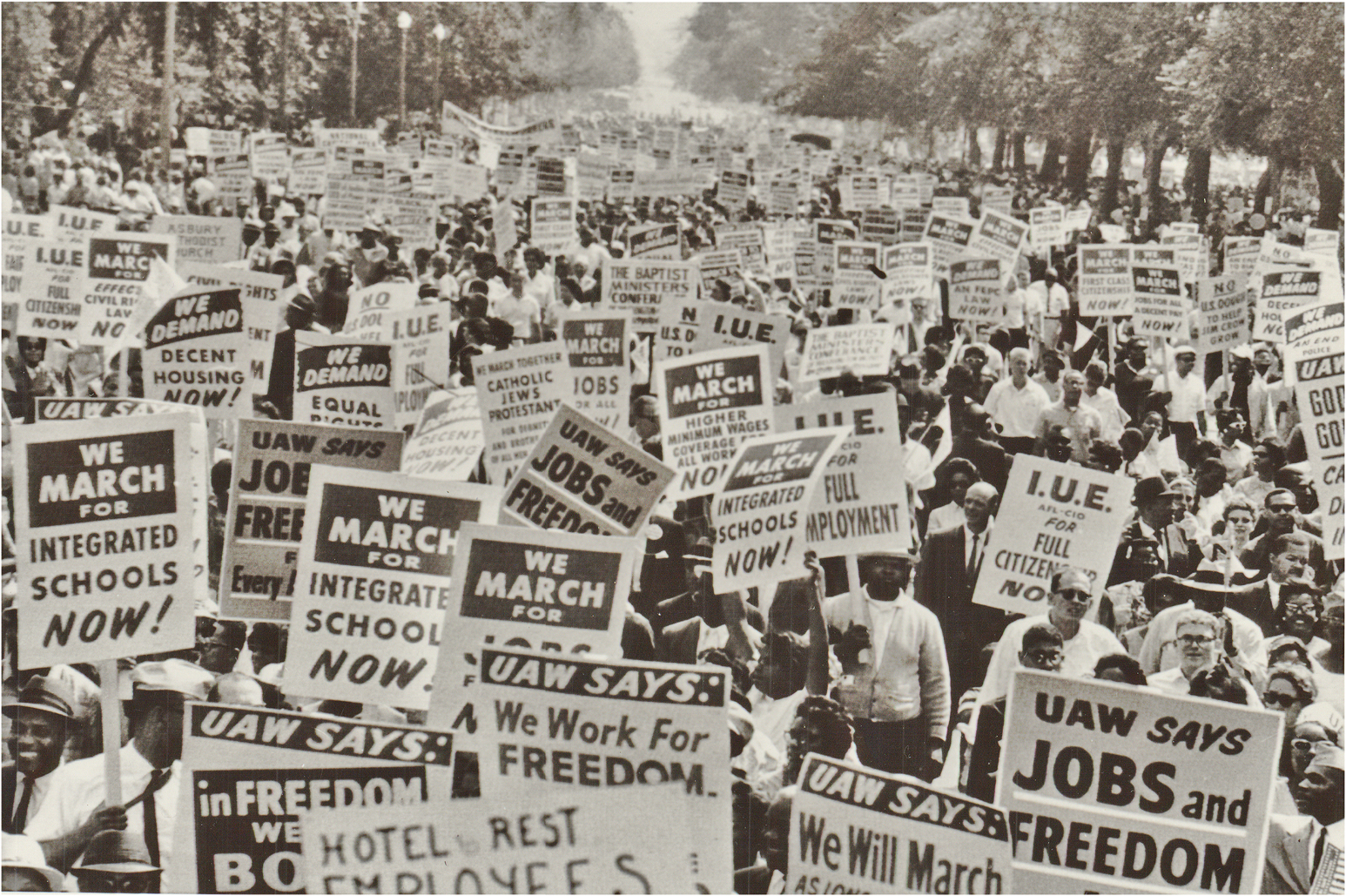

Marchers fill Constitution Avenue during the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

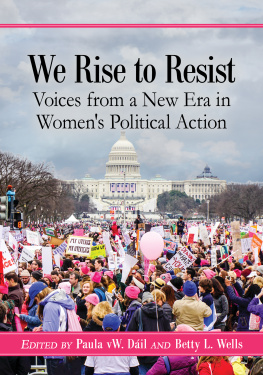

A crowd of marchers on Pennsylvania Avenue during the 2017 Womens March on Washington. Photo by Mario Tama

HOW TO READ A PROTEST

Protests workjust not, perhaps, the way you think.

When youre in the midst of a demonstration, especially a very large one, the sense of collective power is stirring and immediate. Theres a great feeling of purpose and unity when you stand with a huge crowd of other people who share your outrage over an injustice and your eagerness for action. Joining a protest, whatever the cause, gives you the direct bodily experience of being part of something larger than yourself. In a literal and immediate way, you add your heart and your voice to a movement.

But afterward, you might wonder if thats all there is. You march, and it feels good to march, but did the marching matter? And if it did, what exact difference did it make? Do protests change policy? Do they change minds? Or do they just let off steam? Millions of Americans have taken to the streets in recent times, breaking previous records for protest participation, but theres widespread skepticism around demonstrationsa suspicion that protests are purely expressive, a venting of frustration with no quantifiable effect, and that the real work of reform happens through established channels of influence like elections and lobbying. Every time theres a major wave of protests in the United States, a flurry of think pieces follows, questioning whether demonstrations accomplish anything that can be measured. We celebrate past protests that we think did have lasting impact, from the stately 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom to the unruly 1969 Stonewall riots that kicked off the modern LGBTQ movement, but theres often a gestural quality to the acclaim, a broad sense that these actions helped create change, but no detailed accounting of exactly how and why.

Some protests, of course, have no more enduring effect than a gust of wind. There are failures as well as successes in any area of human endeavor, and with protests, the odds are against you from the start. By definition, people demonstrate when normal channels are blocked or unresponsive, when institutions allow injustice to flourish, when the powerful act with impunity. Protests are what political scientist and anthropologist James C. Scott famously called weapons of the weak, used by those who lack the power to achieve their goals through official means. The ultimate measure of a movements success may be if it can move from protest to power, from an outside critique to inside influence, but history moves slowly and unevenly. Structures of power are entrenched and resilient, and injustices go deep. The work of movements is filled with setbacks, reversals, and defeats, and victories are often partial or fragile or both. You may need many years of changing attitudes before you can begin to change policy. You may lose for a very long time before you begin to win. If power conceded without demands, protests would never be necessary.

Protests come in many forms, and happen on wildly varying scales, from a single individual kneeling on a football field to a million people marching through the streets of a major city. There are as many kinds of protests as there are tools in a well-stocked toolbox, and part of the difficulty in coming to terms with what protests do is that they dont all work in the same way. A silent vigil, say, and a freeway blockade are as different in character and effect as a sanding block and a sledgehammer. A vigil is a bid for public sympathy, an appeal to the heart and to common ground. A blockade is intentionally polarizing and controversial; in creating a logistical crisis, it seeks to create a political one, forcing those in power to respond. Successful movements tend to use many different tactics, of which protests are only the most visible, and skilled organizers will use protests of different kinds at different moments in an unfolding campaign.

The most iconic form of protest in America is the mass march, exemplified by the legendary 1963 event where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. delivered his I Have a Dream speech. Mass protests may be the hardest of all to evaluate, even as theyve become recurring fixtures of American political life. At first glance, they all look similar, with huge crowds converging on the nations capital or some other major city to take a public stand. But they are not all alike. Mass protests have been organized very differently over time, and their function has varied and evolved as part of a long series of shifts in the nature of movements and activism in America. Sometimes, a huge demonstration can function like the capstone to a movement, as happened with the 1963 march, which is widely viewed as representing what a successful protest can be. On other occasions, mass protests can channel vast anger with seemingly no effect on the course of events, as happened on the eve of the Iraq War in 2003. In the hope of deterring President George W. Bush from waging a war on false pretenses, millions around the globe poured into the streets for what remains the single largest day of protest in world history; the massive outcry, however, failed to stop the Bush administrations rush to war. And, in rare and remarkable instances, a mass mobilization can help galvanize and energize a sprawling new movement, as the 2017 Womens Marches did with the resistance to Trump. These nationwide marches were organized differently from any major protests in American history, and the bottom-up, women-led way they came together gave them a powerful and unprecedented movement-building impact. If you want to understand what protests do and when and how they work, you first have to understand their character: You need to know how to read a protest.