Public Outrage and Protest

Other Books in the At Issue Series

Americas Infrastructure

Celebrities in Politics

Ethical Pet Ownership

Male Privilege

The Opioid Crisis

Political Corruption

Presentism

The Role of Religion in Public Policy

Troll Factories

Vaping

Wrongful Conviction and Exoneration

Published in 2020 by Greenhaven Publishing, LLC

353 3rd Avenue, Suite 255, New York, NY 10010

Copyright 2020 by Greenhaven Publishing, LLC

First Edition

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form

without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer.

Articles in Greenhaven Publishing anthologies are often edited for length to meet page requirements. In addition, original titles of these works are changed to clearly present the main thesis and to explicitly indicate the authors opinion. Every effort is made to ensure that Greenhaven Publishing accurately reflects the original intent of the authors. Every effort has been made to trace the owners of the copyrighted material.

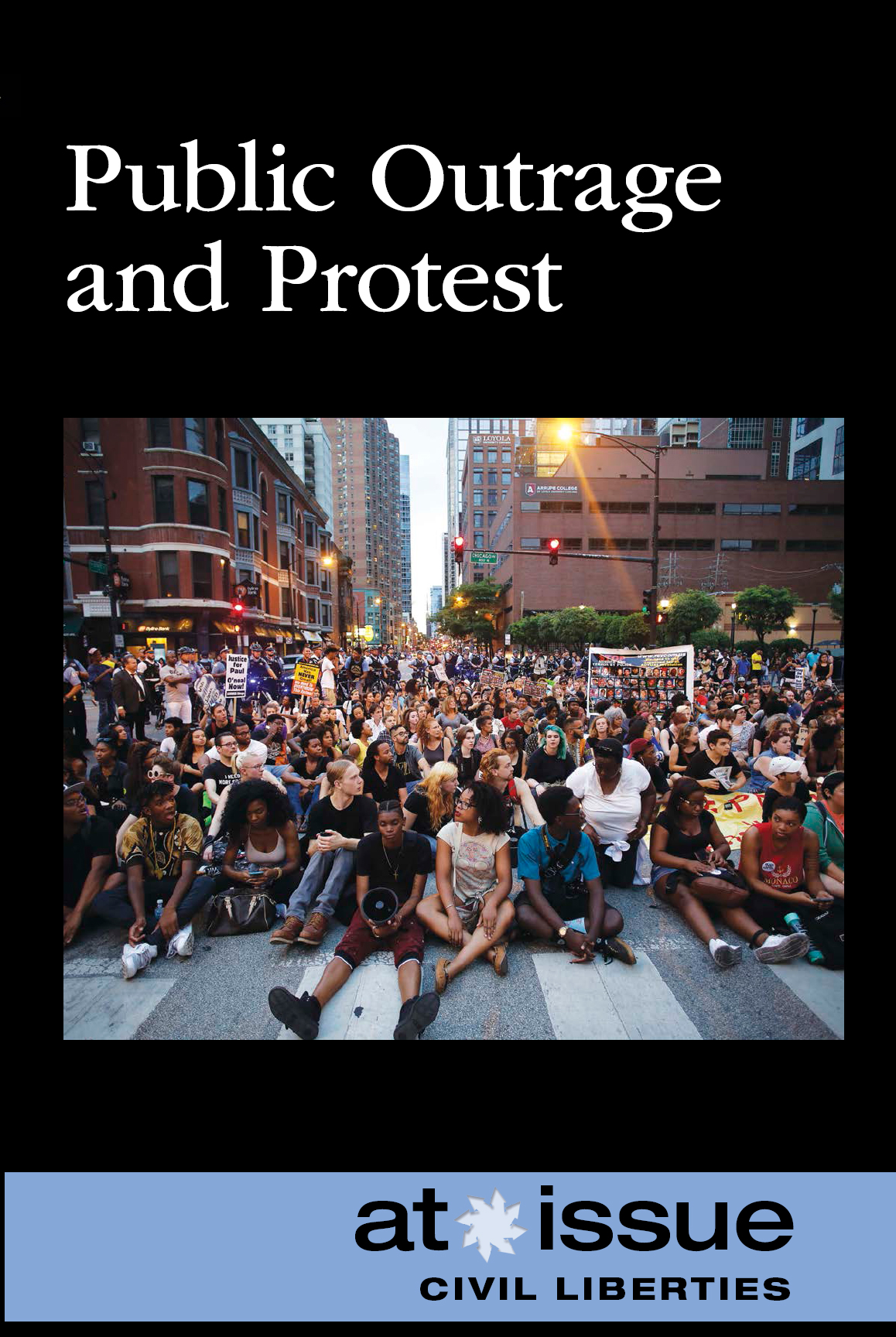

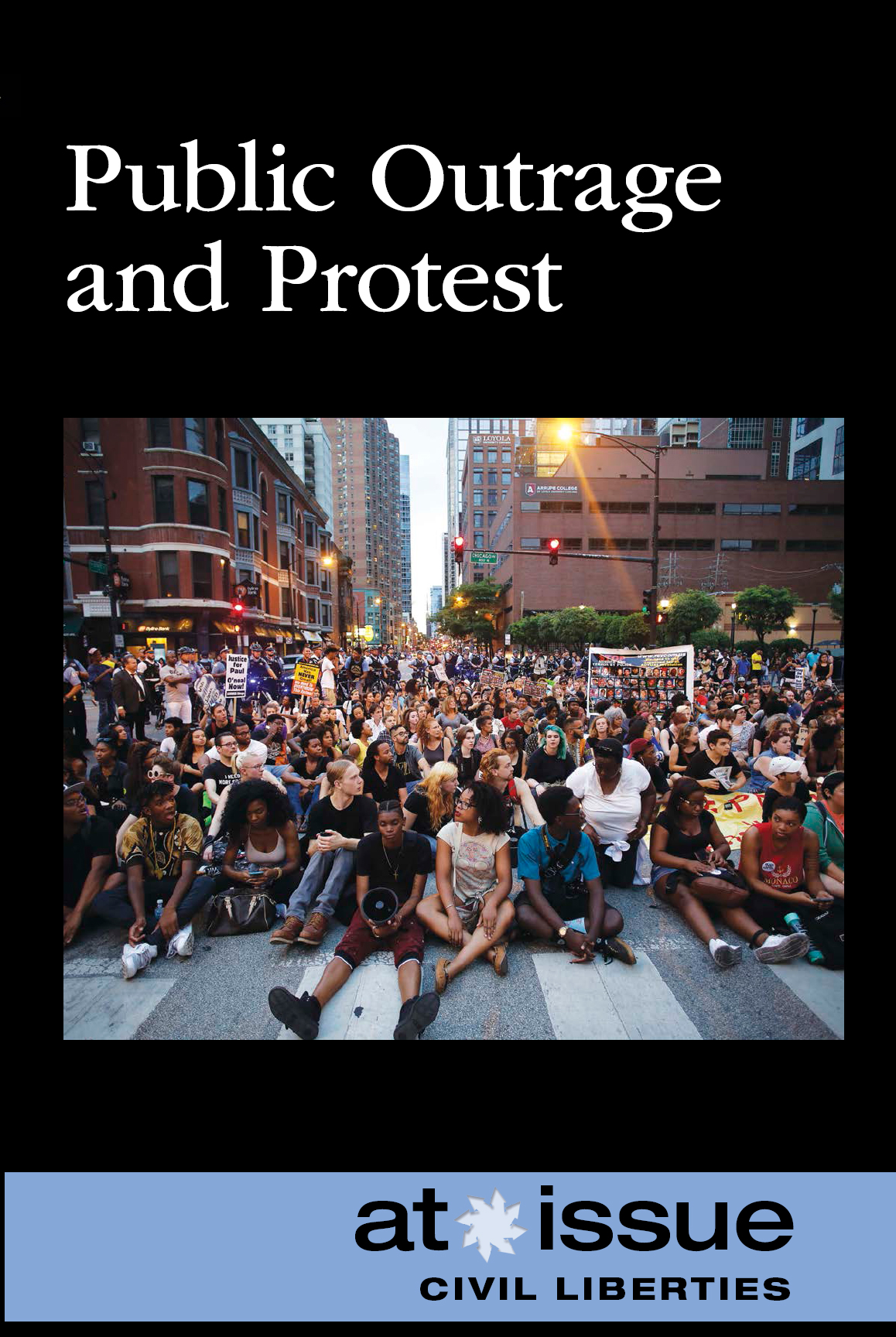

Cover image: Joshua Lott/Getty Images

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data

Names: Doyle, Eamon, 1988-editor.

Title: Public outrage and protest / Eamon Doyle, book editor.

Description: First edition. | New York: Greenhaven Publishing, 2020. | Series: At issue | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Audience: Grade 9 to 12.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018058990| ISBN 9781534505278 (library bound) | ISBN 9781534505285 (pbk.)

Subjects: LCSH: Political violenceUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | Protest movementsUnited StatesJuvenile literature. | Political cultureUnited StatesJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC HN90.V5 P83 2020 | DDC 303.6dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018058990

Manufactured in the United States of America

Website: http://greenhavenpublishing.com

Contents

Corey Dade

Kenya Downs

Yemisi Akinbobola

Jonathan Haidt

Jeffrey M. Berry and Sarah Sobieraj

Ashwini Tambe

Dave Davies

Dan La Botz

Eric Westervelt

Andrew Gumbel

Jamilah King

William H. Westermeyer

Timothy Summers

Mat dos Santos

Alan Greenblatt

Dean Baker

Introduction

O ne of the many unique features of democratic society is the presence of legitimate protest and public political dissent. In the context of traditional or authoritarian forms of government, such behavior is typically forbidden (either by law or edict) and likely to be met with repressive force. But in a democracy, citizens are theoretically free to express dissent and opposition to elected officials and the agencies of government, and to do so in public without fear of reprisal from law enforcement. The benefits of such an arrangement are largely self-evident; when citizens are able to express themselves freely in addition to the formal power they wield in the electoral process, it will theoretically encourage those in power to pursue policies that promote happiness and well-being as conceived by their constituents.

For its part, the United States has a long tradition of spirited public demonstration, a tradition that has included moments of inspiring positivity as well as of violence and hatred. This reflects one of the basic trade-offs of democratic governance: that freedom (of speech and demonstration) is often disruptive and can easily become dangerous when emotions run high and large numbers of people are involved. In the 1960s, the Vietnam War and the civil rights movement provoked major, large-scale protests across the country, including the riots outside the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968 and the incident at Kent State University in which four student protesters were shot and killed by members the National Guard. For a time, historians would point to the era as a sort of high-water mark of outrage and political unrest in the United States.

But over the last twenty-five years, the political atmosphere in the United States has become increasingly polarized and acrimonious, prompting more frequent and intense expressions of public outrage. Examples of this trend include the Tea Party demonstrations in the early years of former President Obamas administration as well as the numerous liberal demonstrations in opposition to President Trump and his policies. It appears in many ways as though we have returned to (or perhaps even surpassed) the level of national angst that Americans lived through in the 1960s.

Changes in the media environment have played a major role in laying the groundwork for this renewed tide of national outrage in the United States. Jeffrey M. Berry and Sarah Sobieraj, both professors at Tufts University who collaborate frequently on research related to modern political sociology, outline the medias role in these changes:

The ascent of outrage says more about changing media technologies and regulatory guidelines and the broader culture than it does about the political views of most citizens. Various changes have coalesced to make scream politics a lucrative, sound business strategy. Media regulation has been reduced, freeing outlets to say almost anything. Cable television multiplies outlets competing to grab eyeballs and ears in their own niches. And political life has become intensely personally focused. Together, these shifts encourage media strategies unimaginable even 20years ago, when outlets used pleasant and inoffensive content to appeal to the broadest possible audiences. Nowadays, controversial, attentiongrabbing content helps to draw an audience in a cluttered media landscape characterized by seemingly limitless options.

The chain of events and social transformation that Berry and Sobieraj describe shows that the way people receive information has a profound impact on the way that they translate that information into political preferences and action. This clearly has major implications for political and policy professionals as they seek to understand voter preferences and the temperature of the electorate in general. But, ultimately, protest and outrage represent something broader and deeper than the events or the tenor of any one historical era or policy issue.

Democracy is built on the concept of government by consent and public figures, whose power depends on the results of elections. In the broad history of human civilization, democracy stands out against the backdrop of cruelty and suffering that other forms of government and social organization (tribal societies, feudal systems, dictatorships) have caused. In this context we can see protest as a vehicle for individuals to protect themselves from the vicissitudes of human power structures. Elected officials understand that widespread outrage and public protest are an indication that their position may be in jeopardy. It helps them to understand how policies are affecting their constituents and how their constituents feel about it. In other words, protest is a channel through which citizens can exert influence separately from the normal electoral process in a context from which conflict is unlikely to disappear.

This is partly the result of the fact that we live in a large, diverse, pluralistic society and partly the result of competitive social dynamics that emerge around free market economies. But it also has to do with evolutionary psychology and basic aspects of human nature. In an essay titled The Age of Outrage, the moral psychologist Jonathan Haidt outlines his theory on the inevitability of social and political angst, a theory he developed in his awardwinning and highly controversial book

Next page