Buffalo Bills Wild West Warriors

A Photographic History by Gertrude Ksebier

Michelle Delaney

Contents

Dedicated to

the late Eugene Ostroff,

longtime Smithsonian curator of photography,

and my parents,

Barbara and the late Michael J. Titanic

TWENTY YEARS AGO, AS A GRADUATE STUDENT IN AMERICAN

Studies at the George Washington University, I was first introduced to the vast collections of the Smithsonian Institutions National Museum of American History (NMAH). Following a series of volunteer and internship positions, I was hired for a position in the Division of Photographic History. Even as a novice in the field of photography, I was quick to absorb the outstanding nature of this unique century-old collection incorporating the history of the science, technology, and art of photography from its beginnings in 1839 to the present.

It has always been my expectation to research, publish, and exhibit the Native American portraits of the Museums Gertrude Ksebier collection. The Smithsonians holdings represent one of the finest collections of her work. As the leading American portrait photographer of her time, Ksebiers role in the establishment of photography as a fine art in this country cannot be understated. As a founding member of the Photo-Secession in 1902, she worked with photographers Alfred Stieglitz and Edward Steichen to reach broader audiences and inspire photographers across the nation, and in Europe, to the possibilities of pictorialism, or art photography.

The Smithsonian holds more than 100 of Ksebiers original platinum photographs (portraits) of the Sioux Indian performers with Buffalo Bills Wild West. Previous articles and book research have never yielded a comprehensive discussion or presentation of these images. I hope this book will serve as an important reference tool for those interested in the history of American photography, Native Americans, Buffalo Bill Cody, and the real and mythic Wild West.

My research efforts have benefited greatly from the assistance and guidance of the following curators, librarians, and archivists: Linda Clark and Ann Marie Donoghue, McCracken Research Library, Buffalo Bill Historical Center, Cody, Wyoming; Verna Curtis, Department of Prints and Photographs, Library of Congress, Washington, DC; Mia Fineman, Department of Photographs, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY; Simon Bieling, Department of Photographs, Museum of Modern Art, New York, NY; Stephen Pinson, Department of Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library, New York, NY; staff of the Manuscript Division, New York Public Library, New York, NY; Marsha Morton, Pratt Institute, Brooklyn, NY; L. Rebecca Johnson Melvin, Gertrude Ksebier Papers, University of Delaware Library, Newark, DE; and Janet Broske, University Gallery, University of Delaware, Newark, DE.

Fellow staff at the Smithsonian have generously supported my book project and research. They include many of my colleagues at the National Museum of American History and from across the Institution: Shannon Perich, Photographic History Collection; Jim Gardner, Office of Curatorial Affairs; David Allison, Division of Information Technology and Communications; Joan Boudreau and Helena Wright, Graphic Arts Collection; Nancy Brooks, editor, Office of Museum Management Services; Vanessa Broussard, David Haberstich, Craig Orr, Kay Peterson, and Susan Strange, Archives Center; Bonnie Lilienfeld, Fath Ruffins, Rayna Green, and Steve Velasquez, Home and Community Life Collection; Dwight Bowers Blocker and Stacey Kluck, Division of Music, Sports and Entertainment; Ann Shumard and Frank Goodyear, Department of Photographs, National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution; Eleanor Harvey, Smithsonian American Art Museum; Joanna Cohan Scherer, Handbook of North American Indians, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution; Daisy Njoku and Vyrtis Thomas, National Anthropological Archives, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution; Chris Cottrill, Mike Hardy, Jim Roan, and Stephanie Thomas of the Smithsonian Libraries; and my extraordinary Smithsonian interns Meg Angelakos, Tim Bauer, Kate Diggle, Samia Elia, Heather Heckler, Katie Morris, and Vanessa Pares. I am also grateful to the many members of the NMAH Collections Committee for their support of the project.

A few scholars have generously mentored me throughout various stages of research: Paula Fleming, retired archivist and specialist in Native American photography at the Smithsonians National Anthropological Archives; Joy Kasson, author and professor of American studies and English at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill; and Barbara L. Michaels, photo historian and author of the only comprehensive Ksebier biography.

Smithsonian photographers John Jones and John Dillaber, and David Sterling of Sterling Prepress all labored diligently, dedicating countless hours to producing the best digital reproductions of the Ksebier photographs for this publication.

HarperCollins editor Donna Sanzone and her colleagues have continually provided enthusiasm and invaluable guidance for this project from their first glance at Ksebiers original prints.

To my family and close friends, I thank you for your patience and encouragement, especially my husband, Paul, and sons, Paulie and Connor, who have helped me to balance work, research, and family fun, including one great trip to the Wild West!

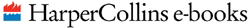

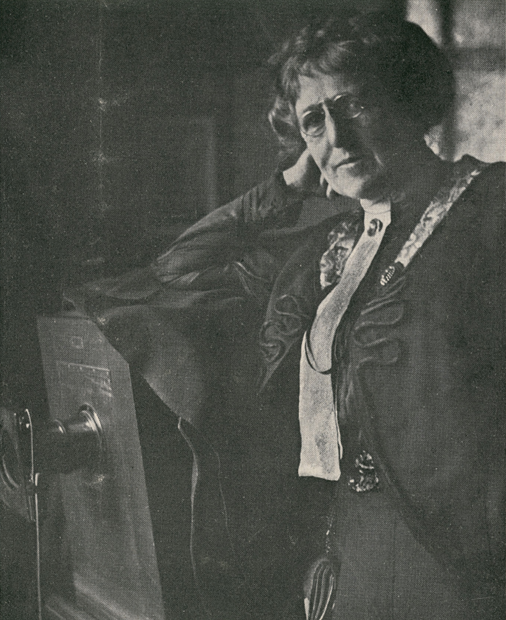

1. Gertrude Ksebier in her studio by W. and G. Parrish, St. Louis, MO, circa 1910, reproduced in the Bulletin of Photography, June 8, 1910.

IN 1898, NEW YORK PHOTOGRAPHER GERTRUDE KSEBIER (18521934) EMBARKED ON A DEEPLY PERSONAL PROJECT, CREATING A SET OF PRINTS THAT RANK AMONG THE MOST COMPELLING OF HER CELEBRATED BODY OF WORK. KSEBIER WAS

on the threshold of a career that would establish her as both the leading portraitist of her time and an extraordinary art photographer. Her new undertaking was inspired by viewing the grand parade of Buffalo Bills Wild West troupe en route to Madison Square Garden for several weeks of performances. Ksebier had spent her childhood on the Great Plains, and retained many vivid, happy memories of living near, and playing with, Native American children. She quickly sent a letter to William Buffalo Bill Cody (18461917), requesting permission to photograph Sioux Indians traveling with the show. Within a matter of weeks, Ksebier began a unique and special project photographing the Indiansmen, women, and childrenformally and informally. Friendships developed, and her photography of these Native Americans continued for more than a decade.

Ksebier pursued this priceless opportunity to document the fast-vanishing life and customs of the Western tribes. Unlike many other photographers working to photograph Native Americans at the turn of the centuryespecially Edward Curtisshe initiated a studio project aimed at representing Indian performers as individuals in a time of transition. Her reputation as a pictorialist, or art photographer, may have been discussed with Cody, further encouraging the portrait sessions. Within several years, Ksebier was to establish herself as the leading portrait photographer in the United States and one of the few Americans accepted into the prestigious international photographic salons of Europe.

Cody and Ksebier were similar in their abiding respect for Native Americans and their culture. This set them apart dramatically from most Americans who retained a more romantic concept of vanishing Indians, fostered by government and news sources, which helped to sustain the notion of Indians as wild savages. At different points in their respective lives, each had maintained meaningful relationships with Plains Indians. Although there is no evidence that Cody and Ksebier ever spent time together, there are many commonalities linking their independent interests in Native Americans, their heritage and their potential place in twentieth-century American society. Cody used his influence with United States government officials in Washington, D.C., to secure Indian performers for his Wild West show. Vastly popular with the general public, the Show Indians were freed from the restraints of the government reservations and allowed to travel the United States and Europe. Their performances included reenactments of famous battles, horse races, and tribal dances. Of course, Cody benefited financially from his long-standing relationship with the Dakota Sioux Indians and various other tribes.