This book made available by the Internet Archive.

In memory of Yang He Tsing and Bessie Cronbacb Lowenhaupt, women of storied courage

PREFACE

In 1971 media around the world picked up on the discovery of a Stone Age tribe in the southern Philippines. The Tasaday, it was said, were everything an urban audience wanted to hear about the good kind of primitives. They swung playfully around on vines, wore nothing but orchid leaves, and had no word for war. They were innocent and eager for protection from the international media and the Philippine state, in the person of Manuel Elizade, the director of the president's special commission on minorities. The Tasaday called Elizade a god. In 1974, Elizade closed their territory to visitors, to protect them from loggers and other exploiters from the modern world.

Perhaps it is not surprising that in the 1980s, after both Elizade and his patron President Marcos had fled the country in disgrace (Elizade was later to return), journalists arrived back in Tasaday country to expose the "hoax" of the Tasaday. The most radical claims argued that the Tasaday were paid actors who had been told to play at being primitives. Indeed, these claims forced a debate in which either the Tasaday were an archaic community that had been entirely isolated for thousands of years or they were cynical members of a rural proletariat forced to portray a contrived communal existence. Less remarked upon was the evidence that there might be a real Tasaday community but one not quite as pristine as Elizade and his media agents claimed; either the Tasaday were completely separate from the imagined "us" of modernity or else they weren't interesting enough to talk about.'

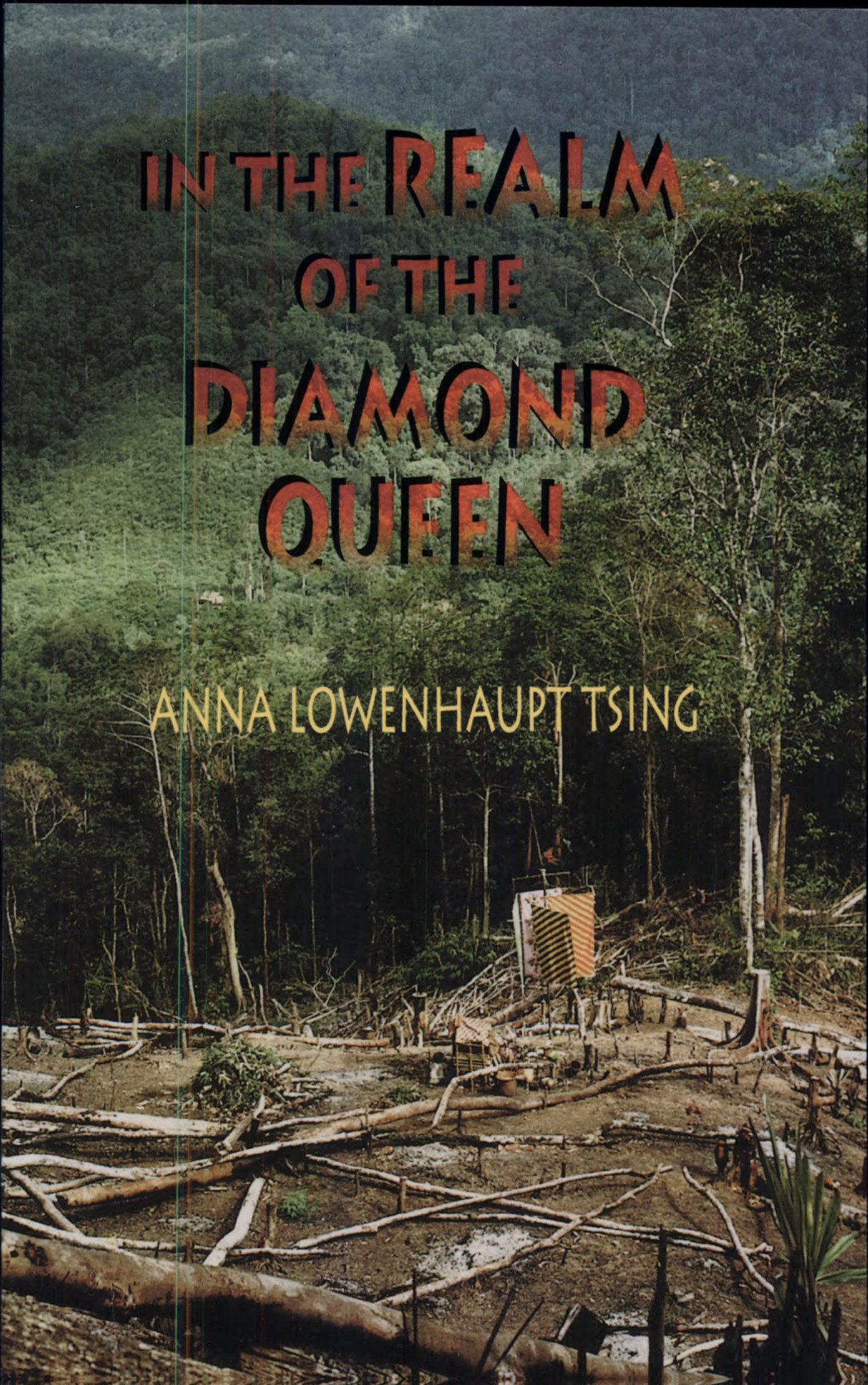

By 1990, media attention had turned to another rainforest people of Southeast Asia: the Penan hunter-gatherers of the forests of Sarawak, East Malaysia, the northern part of the island of Borneo. Media attention

x Preface

was sparked by Penan protests against logging; this time, the media fought state policy rather than being directed by it. From the start, local activists, from the village to the national level, were involved. The logging protests were at least loosely coordinated by the work of Sahabat Alam Malaysia, the Malaysian Friends of the Earth. Yet the news the media carried looked much like the original Tasaday story: The Penan were gentle innocents of the forest; until logging began, they lived encapsulated in their own timeless, archaic world. Ignoring the sophistication of Penan and other Sarawak activists, films and articles focused on the story of Bruno Mansur, a Swiss adventurer who had gone back to nature with the Penan. In two feature-length films, Mansur was depicted as the only conduit for outside knowledge about the isolated and shy Penan. Mansur, like Elizade, would be the champion of the tribes. 1

The story of the Penanlike that of the Tasaday before themwas carefully orchestrated to offer urban audiences something they could understand. Media writers and ecology activists alike figured that only by invoking the abyss between the primitive and the modern would they have a story to tell. Since primitives, as a dying breed, are no longer thought to be dangerous, the story has provoked sympathy, curiosity, and romance. If the Penan were depicted as "modern" people living in an out-of-the-way place, urban audiences would suspect that Penan were merely shabbier, less educated and privileged versions of themselves. One could feel sympathetic, but there would be nothing interesting to learn from the Penan and thus no reason to single them out for special attention. Perhaps a few activists worry about the Tasaday parallel: If the Penan were "exposed" as more cosmopolitan than some of their portrayals imply, would they lose international support and thus all possibility of a Penan forest biosphere reserve? But no alternatives have emerged. Thus, those who, with all good intentions, represent the Penan to the world ignore the dangers of the Tasaday precedent and, with some awkwardness, construct a threatened Eden in the rainforest.

What these stories of the Tasaday and the Penan suggest to me is the poverty of an urban imagination which systematically has denied the possibilities of difference within the modern world and thus looked to relatively isolated people to represent its only adversary, its dying Other. The point of this book is to develop a different set of conceptual tools for thinking about out-of-the-way placesand, in particular, about Southeast Asian rainforest dwellers. Like the Tasaday and the Penan, the Mera-tus Dayaks of southeast Kalimantan (Indonesian Borneo) are neither my nor anybody's "contemporary ancestors." They share with anyone who

Preface xi

might read this book a world of expanding capitalisms, ever-militarizing nation-states, and contested cultural politics. They also speak from perspectives that are distinctive from those of urban Indonesians, or non-Indonesians, but these are distinctions forged in dialogue, not in archaic isolation. I use the concept of marginality to begin discussion of such distinctive and unequal subject positions within common fields of power and knowledge.

To describe Meratus Dayaks as an embryo-like Other across an abyss of time and civilization would be to ignore their current political and cultural dilemmas. Yet it is difficult to speak harshly of the romance of the primitive, because it is a discourse of hope for many Europeans and North Americans, as well as a growing number of urban Indonesians concerned about deteriorating social and natural environments. Many people that I care about and respect know the primitive as the dream space of possibility against the numbing monotony of regulated life and the advancing terrors of ecological destruction, corporate insatiability, and military annihilation. Perhaps it seems hard-hearted on my part to work so hard to disturb these fragile dreams. I can only argue that there is also possibility and promise in the directions 1 suggest in this book. My sense of promise derives from attention to the cultural richness of the cosmopolitan worldand to the possibilities for play and parody as difference is continually constructed and deconstructed. This attention derives from an alertness I acquired in working with the Meratus Dayak woman I call Uma Adang; our encounters frame this book. Nor is this attention just another detached, ironic deconstruction of the play of categories. There is also curiosity herea refusal to be numbed by terror in a terrifying world. The book is a self-conscious exploration of the possibilities of living with curiosity amidst ongoing violence.

I first travelled to the Meratus Mountains of South Kalimantan, Indonesia, in September 1^79 and stayed through August 1981. I visited the same people and places again over several months in 1986. Much of the mountain area offers a densely forested and rough terrain occasionally dotted with fields and houses and crisscrossed with trails whose paths may change after a night of rain. This is a difficult, confusing terrain for administrators and tourists, and its maps continue to present conflicting detail concerning vegetation, settlement, and district borders. In this book I argue that the imagined constraints of travelling over this terrain, together with the necessity and pervasiveness of travel, form a technology of regional integration that holds in place a set of discussions constituting