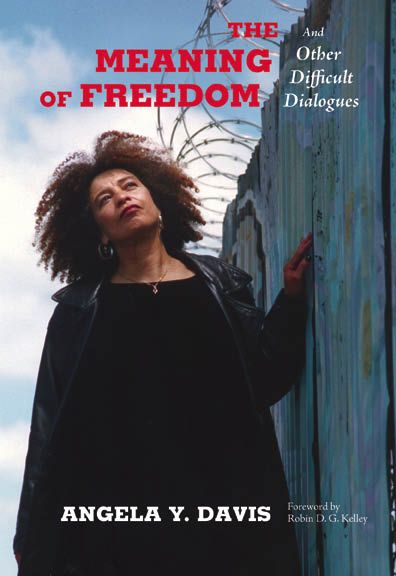

Angela Y. Davis

Foreword by Robin D. G. Kelley

Copyright 2012 by Angela Y. Davis

Foreword 2012 by Robin D. G. Kelley

All Rights Reserved.

Davis, Angela Y. (Angela Yvonne), 1944

The meaning of freedom / by Angela Y. Davis ; with a foreword by Robin D. G. Kelley.

p. cm. (Open media series)

1. United StatesSocial conditions1980- 2. United StatesPolitics and government1989- 3. Liberty. 4. Racism. 5. Civil rights. I. Title. II. Series.

261 Columbus Avenue, San Francisco, CA 94133.

Foreword

By Robin D. G. Kelley

What is the meaning of freedom? Angela Daviss entire life, work, and activism has been dedicated to examining this fundamental question and to abolishing all forms of subjugation that have denied oppressed people freedom. It is not too much to call her one of the worlds leading philosophers of freedom. She stands against the liberal tradition of political philosophy, the tradition derived from Hobbes and others that understands freedom as the right of the individual to do what he wishes without fetters or impediments, as long as it is lawful under the state. This negative liberty or freedom places a premium on the right to own property, to accumulate wealth, to defend property by arms, to mobility, expression, and political participation. Daviss conception of freedom is far more expansive and radicalcollective freedom; the freedom to earn a livelihood and live a healthy, fully realized life; freedom from violence; sexual freedom; social justice; abolition of all forms of bondage and incarceration; freedom from exploitation; freedom of movement; freedom as movement, as a collective striving for real democracy. For Davis, freedom is not a thing granted by the state in the form of law or proclamation or policy; freedom is struggled for, it is hard-fought and transformative, it is a participatory process that demands new ways of thinking and being. Thus it is only fitting that she is among the few major contemporary thinkers who takes seriously Karl Marxs 1845 injunction that The philosophers have only interpreted the world, in various ways. The point, however, is to change it.

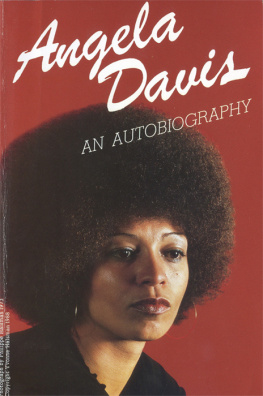

Angela Davis was born and raised in apartheid Birmingham, Alabama, under conditions of extreme and blatant unfreedom. She grew up in the 1940s and 50s, when black middle-class homes were being firebombed regularly by white supremacists with the blessings and encouragement of police chief Eugene Bull Connor, and when black opposition to racism eventually brought the city to a standstill. She was nurtured by activist parents whose best friends were members of the Communist Party, and she came of age amidst a community in struggle. By the time she enrolled in New York Citys Elisabeth Irwin High School (nicknamed the Little Red School House for its left-leaning philosophy) in 1959, she had already contemplated the meaning of freedom and understood that the question was no mere academic exercise. The quest for freedom drew her to radical philosopher Herbert Marcuse, with whom she studied at Brandeis University. It drew her to the writings of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, and Jean-Paul Sartre, and to France, where she studied abroad. During her stay in Paris, Davis developed an even more global perspective on the quest for freedom by witnessing the French racism against North Africans and the Algerian struggle for liberation. And, sadly, it was in France, in September of 1963, that she learned of the bombing of Birminghams 16th Street Baptist Church and the murder of her childhood acquaintances, Denise McNair, Addie Mae Collins, Carole Robertson, and Cynthia Wesley. Their deaths wedded her to a life of struggle. She knew then, contrary to Jean-Paul Sartres assertions, that there was no freedom in death. Freedom is the right to live, the necessity to struggle.

Davis continued her studies dedicated to producing engaged scholarship. With Marcuses support and encouragement , Davis pursued her doctorate in philosophy at Johann Wolfgang Goethe University in Frankfurt, Germany, with the intention of studying with Theodor Adorno, but by this time Adorno had little interest in engaged scholarship. (Her model at Goethe University was a young professor named Oskar Negt, who never shrank from political engagement and actively participated in the Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund [SDS].) West Germany was too far from the sites of engagement that most mattered to Davis, so after two years she returned to the states to resume her doctoral studies under Marcuses direction at the University of California, San Diego.

The year was 1967, and it seemed as if every aggrieved groupyouth, women, people of coloridentified with liberation struggle. Freedom was in the air, and Davis threw herself mind and body into the movement. The rest of the story is quite familiar: her path from the Black Panthers to UCLA and her tangle with Governor Ronald Reagan, to Soledad Prison and the subsequent campaign that forever associated her name with Freedom. As an incarcerated political prisoner, she became the center of an international movement whose supporters pinned their own freedom to Daviss, concluding that to Free Angela was a blow to the blatant acts of state violence and unfreedom that crushed protests at the Democratic National Convention in 1968, that murdered Salvador Allende in Chile, that justified the dropping of napalm and herbicides on villages as far away as Vietnam and Mozambique. And like so many incarcerated revolutionary intellectuals, such as Antonio Gramsci, Malcolm X, Assata Shakur, George Jackson, and Mumia Abu-Jamal, she produced some of the most poignant, critical reflections on freedom and liberation from her jail cell.

Daviss trial, subsequent acquittal, and struggle to find work in the face of ongoing political repression have only reinforced her commitment to engaged scholarship, her explorations of the meaning of freedom, and her radical abolitionist politics. Even if one is not familiar with her leadership in the Communist Party USA, her role in the founding of the Committees of Correspondence, Agenda 2000, and Critical Resistance, or her prolific body of scholarshipfrom her collection Women, Race, and Class on the politics of reproduction, domestic violence, rape, and women and capitalism; her stunning Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday on the politics of black womens expressive culture; to her more recent manifestoes calling for the end of the prison-industrial complex, Are Prisons Obsolete? and Abolition Democracy the speeches published here prove the point.

Delivered between 1994 and 2009, these public talks reveal Davis further developing her critique of the carceral state, offering fresh analyses of racism, gender, sexuality, global capitalism, and neoliberalism, responding to various crises of the last two decades, and always inviting her audiences to imagine a radically different future. They demonstrate the degree to which she remains a dedicated dialectical thinker. Davis has never promoted a political line, nor have her ideas stood still. As the world changes and power relations shift from a post-Soviet, post-apartheid, post-Bush world to the mythical post-racial one, she challenges us to critically interrogate our history, to deal with the social, political, cultural, and economic dynamics of the moment, and to pay attention to where people are. In the 1990s, she challenged parochialism and creeping conservatism in black movements; told us to pay attention to hip hop and the sigh of youth struggling to find voice; and warned us against nostalgia for the good old days of the 1960s when, allegedly, resistance movements had more leverage and enemies were easier to recognize. And she consistently takes on the prison-industrial complex. Davis frequently returns to the relationship between the formation of prisons and the demand for cheap labor under capitalism, and their unbroken lineage with the history and institution of slavery in the United States. Her powerful critiques of Foucault and other theorists/historians of the birth of the prison reveal the centrality of race in the process of creating a carceral state in the West. The critical question for Davis centers on how black people have been criminalized and how this ideology has determined black peoples denial of basic citizenship rights. Since most leading theorists of prisons focus on issues such as reform, punishment, discipline, and labor under capitalism, discussions of the production of imprisoned bodies often play down or