Acknowledgments

I should not be listed as the sole author of this book, for its ideas reflect various forms of collaboration over the last six years with activists, scholars, prisoners, and cultural workers who have tried to reveal and contest the impact of the prison industrial complex on the lives of peoplewithin and outside prisonsthroughout the world. The organizing committee for the 1998 Berkeley conference, Critical Resistance: Beyond the Prison Industrial Complex, included Bo (rita d. brown), Ellen Barry, Jennifer Beach, Rose Braz, Julie Browne, Cynthia Chandler, Kamari Clarke, Leslie DiBenedetto Skopek, Gita Drury, Rayne Galbraith, Ruthie Gilmore, Naneen Karraker, Terry Kupers, Rachel Lederman, Joyce Miller, Dorsey Nunn, Dylan Rodriguez, Eli Rosenblatt, Jane Segal, Cassandra Shaylor, Andrea Smith, Nancy Stoller, Julia Sudbury, Robin Templeton, and Suran Thrift. In the long process of coordinating plans for this conference, which attracted over three thousand people, we worked through a number of the questions that I raise in this book. I thank the members of that committee, including those who used the conference as a foundation to build the organization Critical Resistance. In 2000, I was a member of a University of California Humanities Research Institute Resident Research Group and had the opportunity to participate in regular discussions on many of these issues. I thank the members of the groupGina Dent, Ruth Gilmore, Avery Gordon, David Goldberg, Nancy Schepper Hughes, and Sandy Barringerfor their invaluable insights. Cassandra Shaylor and I coauthored a report to the 2001 World Conference Against Racism on women of color and the prison industrial complexa number of whose ideas have made their way into this book. I have also drawn from a number of other recent articles I have published in various collections. Over the last five years Gina Dent and I have made numerous presentations together, published together, and engaged in protracted conversations on what it means to do scholarly and activist work that can encourage us all to imagine a world without prisons. I thank her for reading the manuscript and I am deeply appreciative of her intellectual and emotional support. Finally, I thank Greg Ruggiero, the editor of this series, for his patience and encouragement.

About the Author

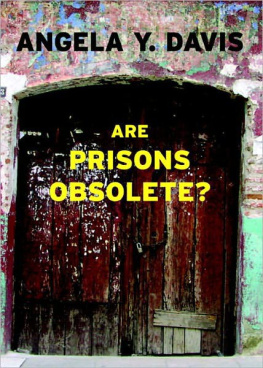

ANGELA YVONNE DAVIS is a professor of history of consciousness at the University of California, Santa Cruz. Over the last thirty years, she has been active in numerous organizations challenging prison-related repression. Her advocacy on behalf of political prisoners led to three capital charges, sixteen months in jail awaiting trial, and a highly publicized campaign then acquittal in 1972. In 1973, the National Committee to Free Angela Davis and All Political Prisoners, along with the Attica Brothers, the American Indian Movement and other organizations founded the National Alliance Against Racist and Political Repression, of which she remained co-chairperson for many years. In 1998, she was one of the twenty-five organizers of the historic Berkeley conference Critical Resistance: Beyond the Prison Industrial Complex and since that time has served as convener of a research group bearing the same name under the auspices of the University of California Humanities Research Institute. Angela is author of many books, including Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude Ma Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday. Her new book, forthcoming from Random House, is Prisons and Democracy.

Resources

CRITICAL RESISTANCE: BEYOND THE

PRISON-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX

www.criticalresistance.org

National Office:

1904 Franklin Street, Suite 504

Oakland, CA 94612

Phone: (510) 444-0484

Fax: (510) 444-2177

crnational@criticalresistance.org

NORTHEAST REGIONAL OFFICE

460 W. 128th Street

New York, NY 10027

Phone: (917) 493-9795

Fax: (917) 493-9798

crne@criticalresistance.org

SOUTHERN REGIONAL OFFICE

P.O. Box 791213

New Orleans, LA 70179

Phone: (504) 837-5348 or toll free (866) 579-0885

crsouth@criticalresistance.org

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH PRISON PROJECT

350 5th Avenue, 34th Floor

New York, NY 10118-3299

Phone: (212) 290-4700

Fax: (212) 736-1300

hrwnyc@hrw.org

www.hrw.org

INCITE! WOMEN OF COLOR AGAINST VIOLENCE

P.O. Box 6861

Minneapolis, MN 55406-0861

Phone: (415) 553-3837

incite-national@yahoo.com

www.incite-national.org/

JUSTICE NOW (JUSTICE NETWORK ON WOMEN)

1322 Webster Street, Suite 210

Oakland, CA 94612

Phone: (510) 839-7654

Fax: (510) 839-7615

cynthia@jnow.org, cassandra@jnow.org

www.jnow.org

THE NATIONAL CENTER ON INSTITUTIONS

AND ALTERNATIVES (NCIA)

3125 Mt. Vernon Avenue

Alexandria, VA 22305

Phone: (703) 684-0373

Fax: (703) 549-4077

info@ncianet.org

www.ncianet.org/ncia; www.sentencing.org

PRISON ACTIVIST RESOURCE CENTER

P.O. Box 339

Berkeley, CA 94701

Phone: (510) 893-4648

Fax: (510) 893-4607

parc@prisonactivist.org

www.prisonactivist.org

PRISON LEGAL NEWS

2400 NW 80th Street, PMB #148

Seattle, WA 98117

Phone: (206) 781-6524

www.prisonlegalnews.org

PRISON MORATORIUM PROJECT

388 Atlantic Avenue, 3rd Floor

Brooklyn, NY 11217

Phone: (718) 260-8805

Fax: (212) 727-8616

pmp@nomoreprisons.org

www.nomoreprisons.org

THE SENTENCING PROJECT

514-10th Street NW #1000

Washington, DC 20004

Phone: (202) 628-0871

Fax: (202) 628-1091

www.sentencingproject.org

IntroductionPrison Reform or Prison Abolition?

In most parts of the world, it is taken for granted that whoever is convicted of a serious crime will be sent to prison. In some countriesincluding the United Stateswhere capital punishment has not yet been abolished, a small but significant number of people are sentenced to death for what are considered especially grave crimes. Many people are familiar with the campaign to abolish the death penalty. In fact, it has already been abolished in most countries. Even the staunchest advocates of capital punishment acknowledge the fact that the death penalty faces serious challenges. Few people find life without the death penalty difficult to imagine.

On the other hand, the prison is considered an inevitable and permanent feature of our social lives. Most people are quite surprised to hear that the prison abolition movement also has a long historyone that dates back to the historical appearance of the prison as the main form of punishment. In fact, the most natural reaction is to assume that prison activistseven those who consciously refer to themselves as antiprison activistsare simply trying to ameliorate prison conditions or perhaps to reform the prison in more fundamental ways. In most circles prison abolition is simply unthinkable and implausible. Prison abolitionists are dismissed as utopians and idealists whose ideas are at best unrealistic and impracticable, and, at worst, mystifying and foolish. This is a measure of how difficult it is to envision a social order that does not rely on the threat of sequestering people in dreadful places designed to separate them from their communities and families. The prison is considered so natural that it is extremely hard to imagine life without it.

It is my hope that this book will encourage readers to question their own assumptions about the prison. Many people have already reached the conclusion that the death penalty is an outmoded form of punishment that violates basic principles of human rights. It is time, I believe, to encourage similar conversations about the prison. During my own career as an antiprison activist I have seen the population of U.S. prisons increase with such rapidity that many people in black, Latino, and Native American communities now have a far greater chance of going to prison than of getting a decent education. When many young people decide to join the military service in order to avoid the inevitability of a stint in prison, it should cause us to wonder whether we should not try to introduce better alternatives.