T.K. Oommen is Chair, Schumacher Centre, and Ford Foundation Chair, Non-traditional Society at Delhi Policy Group, New Delhi. He retired in October 2002 from the Centre for the Study of Social Systems, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi, where he worked for over 30 years. During his distinguished career he has served as President, Indian Sociological Society (199899); President, International Sociological Association (199094); and Secretary-General of the XI World Congress of Sociology (1986). He has been a Visiting Professor at the Department of Sociology, University of California at Berkeley; Visiting Fellow at the Maison des Sciences de lHomme, Paris; Visiting Professor at the Wissenschaftszentrum, Berlin; Visiting Fellow at the Research School of Social Sciences, Australian National University, Canberra; Senior Fellow, Institute of Advanced Studies, Budapest; and Senior Fellow, Institute of Advanced Studies, Uppsala, Sweden.

Professor Oommen is the recipient of all the three Indian awards available to sociologists: The V.K.R.V. Rao prize in Sociology (1981), the G.S. Ghurye prize in Sociology and Social Anthropology (1985), and the Swami Pranavananda Award for Sociology (1997). He has written and/or edited 19 books so far, including Nation, Civil Society and Social Movements: Essays in Political Sociology (2004); Citizenship and National Identity: From Colonialism to Globalism (1997); Alien Concepts and South Asian Reality (1995); Citizenship, Nationality and Ethnicity (1997); The Christian Clergy in India (2000); and Equality, Identity and Pluralism (2002).

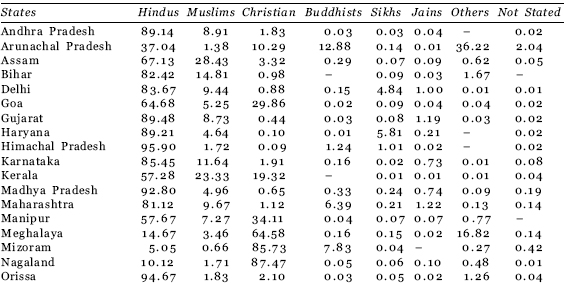

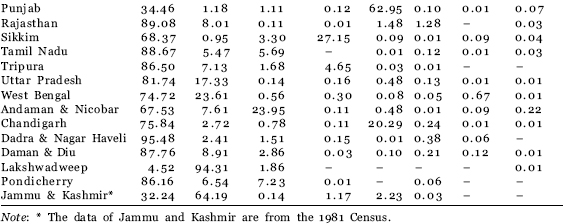

Table 1

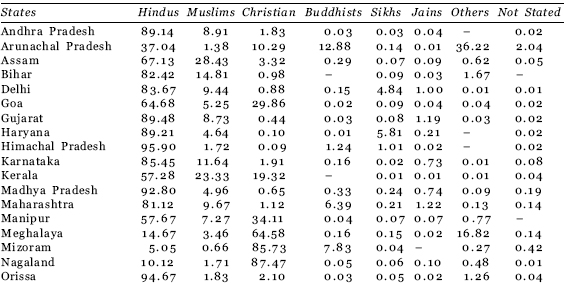

Distribution of Religions in India: States and Union Territories (1991)

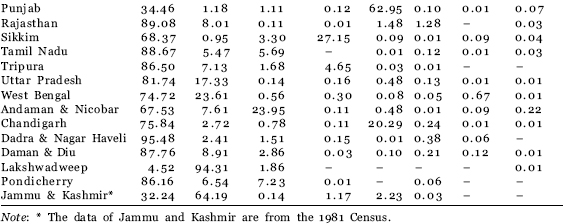

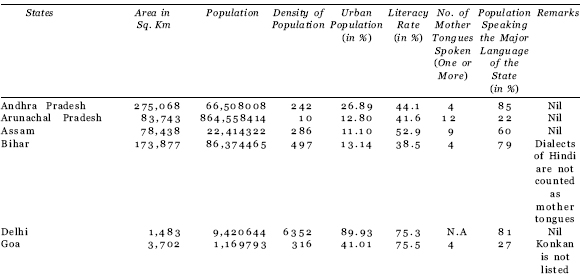

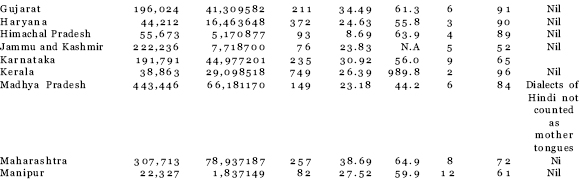

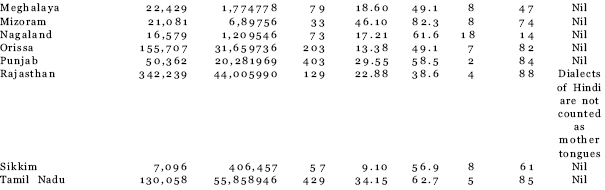

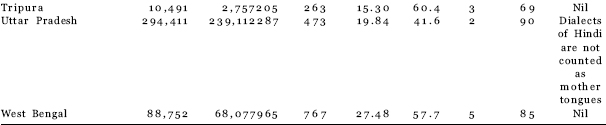

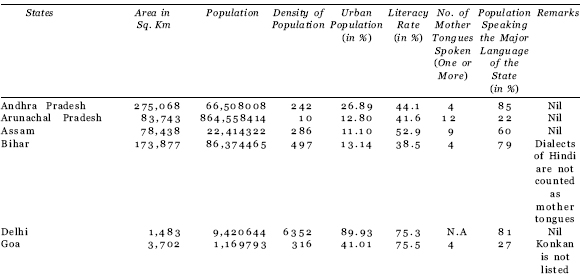

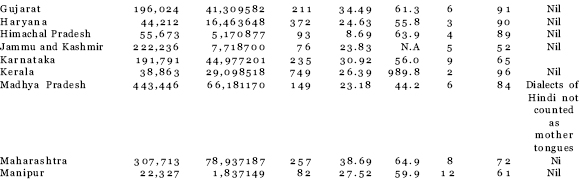

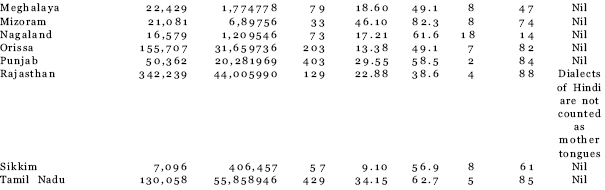

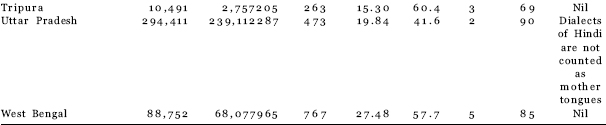

Table 2

Some Features of States in India (1991)

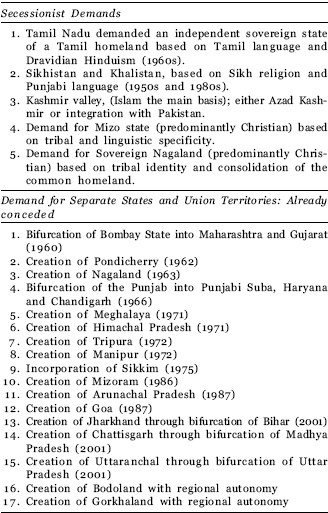

Table 3

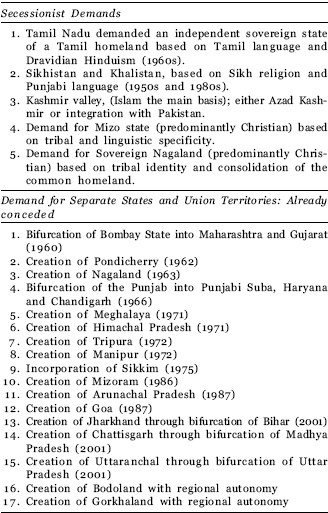

Secessionist and Separatist Demands in Independent India

Table 4

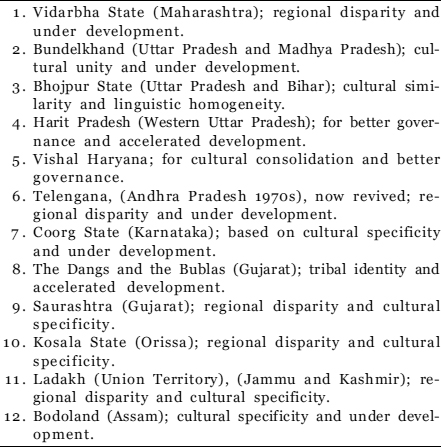

Reasons for Ongoing Demands for Separate States/Union Territories

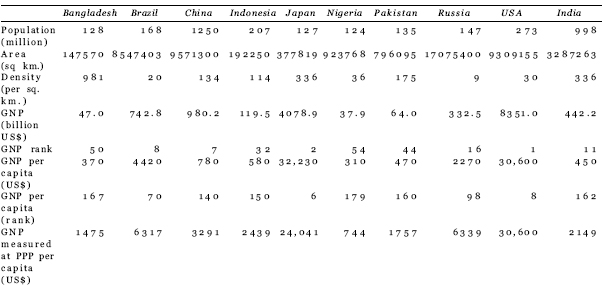

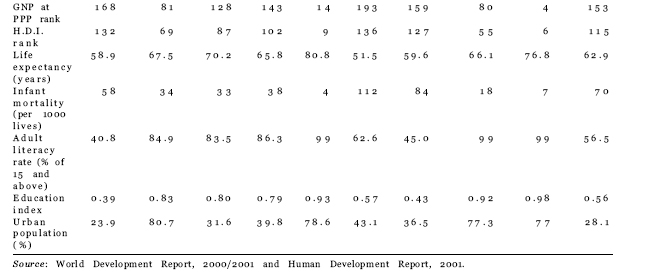

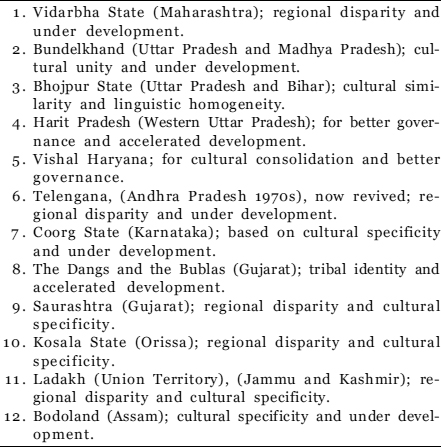

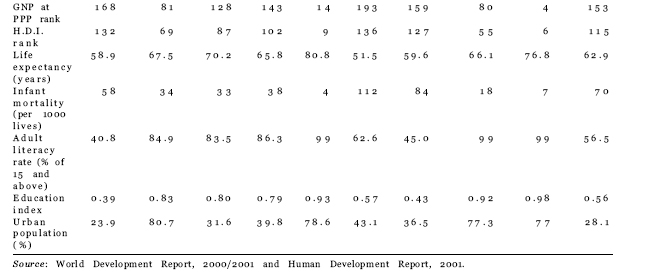

Table 5

100 Million-Plus Countries: Some Socio-economic Features (1999)

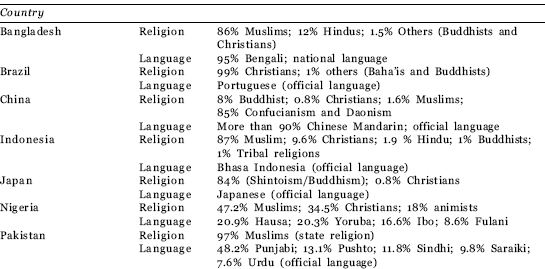

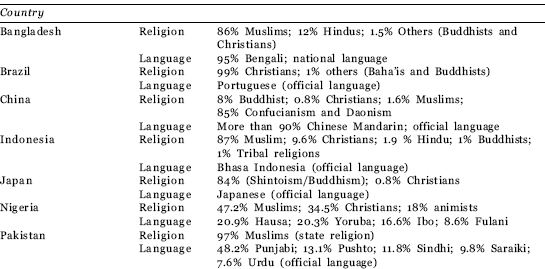

Table 6

Religion and Language Variations in 100 Million-Plus Countries

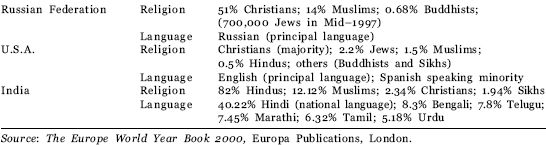

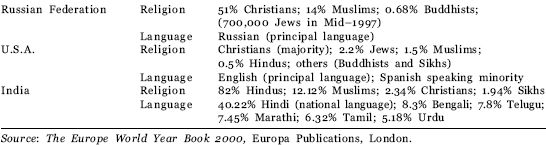

Table 7

Indias Neighbours: Geo-Political Picture

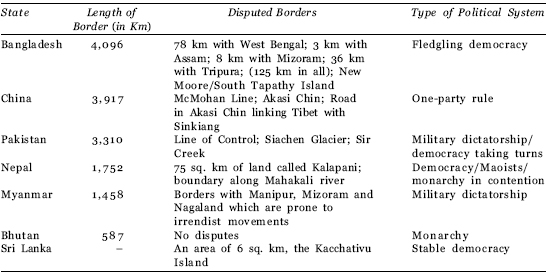

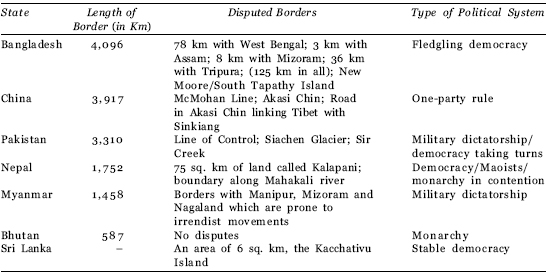

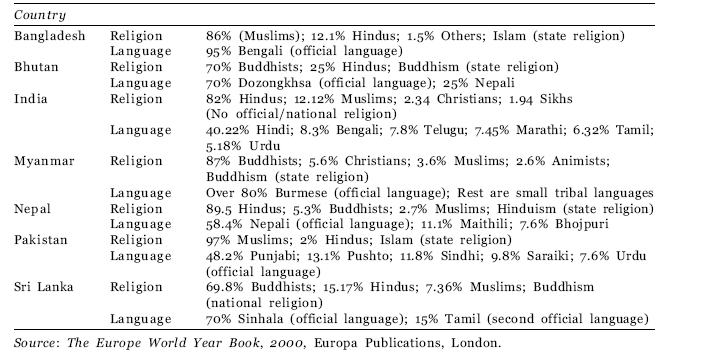

Table 8

Religion and Language Variations in South Asian Countries

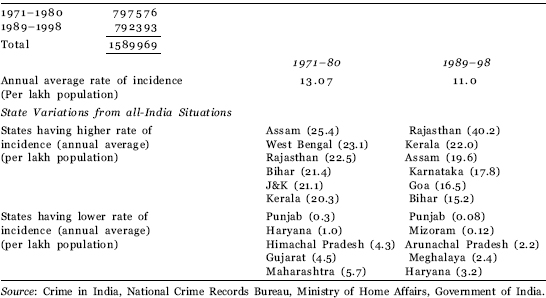

Table 9

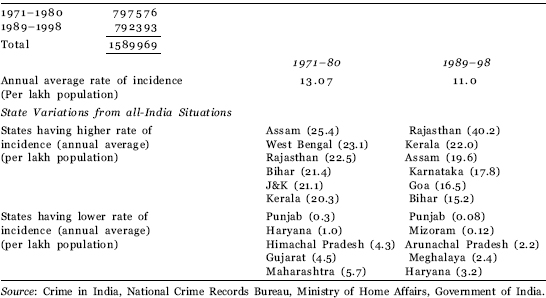

All-India and State Incidence of Communal Riots

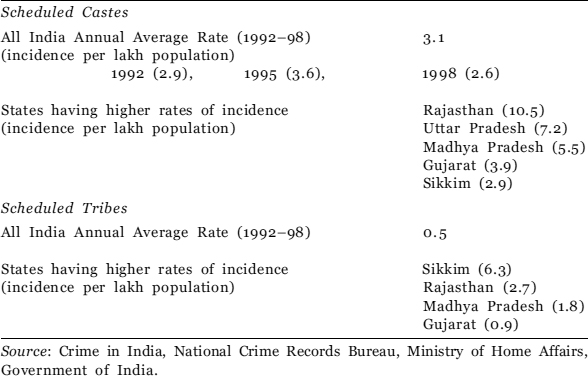

Table 10

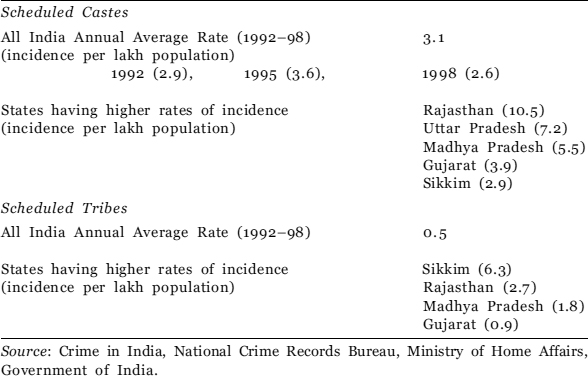

Atrocities Against Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes

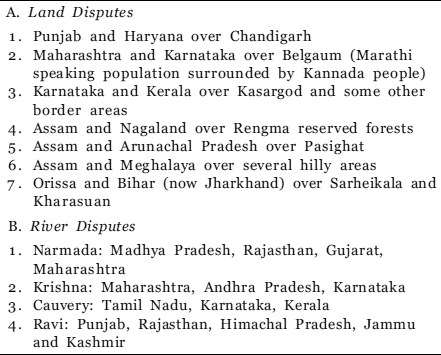

Table 11

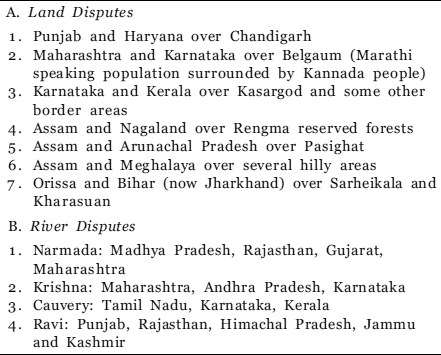

Inter-State Disputes

T o speak of onesixth of humanity for the span of a century within an hour is a stupendous task. To cope with this Herculean task I shall invoke five entry points (i) rural-urban interaction; (ii) tribe-caste-religion nexus; (iii) linguistic re-organisation, and the identity of subaltern nations; (iv) state-civil society interface; and (v) dynamics of change in the family and among youth and women. While these entry points have their own specific trajectories, they are also inter-connected.

I

India no longer lives in her villages, and the challenges posed by urbanisation are many. In 1901 the urban population of India was only 10.85 per cent of the total. It reached 17.3 per cent in 1951. By 1991 it had increased to 25.7 per cent and it was estimated to be 29 per cent by 2001. That is, in the 20th century the urban Indian population grew three-fold. What is more, the present trend indicates that the number of big towns is likely to increase manifold: in 1951 there were five million-plus cities but by 1991 they numbered 23. Finally, the population of urban India is estimated to reach 291 million by 2001, which will be more than the total population of every country in the world, save China.

While pre-industrial urbanisation has existed in all ancient civilisations as an organic part of the rural hinterland, industrial urbanisation has led to a radical rupture between the rural and urban worlds not only in terms of the quality of life in these worlds, but also in terms of the disparity between them. In the case of India this was noted by William Digby, the colonial administrator in 1901: There are two Indiasthe India of the Presidency, of the Chief Provincial cities, of the railway systems, of the hill stations. There are two countries: Anglostanand Hindustan. This trend continued in independent India, the current nomenclature being Bharat (rural) and India (urban). However, the divide between Bharat and India is not as neat and tidy as it is made out to be.

A divide exists within urban and rural settlements. Further, in urban settlements the contrast between the crowded areas without basic amenities in which the majority of urban people live, and the affluent areas which the urban elite inhabit, is stark. Middle-class colonies with moderate facilities come in between.