Chapter 1

Lines of resistance

Histories and movements

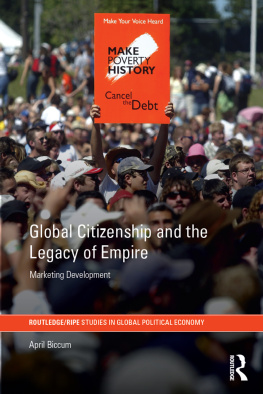

It has been one of the staples of Western historiography to emphasize the imperial process as one focused exclusively on Western activity. That activity can be represented as benign (improving the natives, aiding the Third World), or, at the other extreme, as oppressive (colonial expropriation, economic exploitation, etc.), but in either case it is the West which is deemed to be the dynamic element in the relationship. The possibility that indigenous people might be active agents in the making (if not the writing) of their own histories was something which was rarely if ever entertained by Western writers, and then usually in highly negative terms. One reason for this was that a principal mode of indigenous agency was resistance to Western control, while the typical Western response (historiographical, rather than political or military) was to pretend that it had not happened or was not worth mentioning, or, if that failed, to construe it as out and out treachery (the Indian Mutiny of 1857) or an explosion of atavistic barbarity (the Mau Mau uprising in the 1950s). If the historiographical approach was quietly to obliterate resistance by not including it in the historical record, then this was perhaps no more than the counterpart of the political and military approach, whose aim was literally to obliterate it. In the post-colonial period it has become a matter of some importance not only to recover the histories of native insurgency, but also to analyze them at a theoretical level.

Tracing histories of resistance is obviously far beyond the scope of a chapter such as this. Equally, there are many important figures and other geographical regions whose strong claims to inclusion we have had to ignore. Rather, what we aim to do is to present briefly the ideas of a few of the major thinkers, to suggest some of the important connections (and differences) between them, and thereby to give a sense of the way in which resistance to imperialism in its colonial and neo-colonial moments has thought and organized around shared topics as well as very context-specific ones. A sense of the combinatory possibilities of resistance is important: for instance, in Gandhis use of moral and spiritual arguments to launch very physical (if non-violent) resistance to British colonial rule, or Nggs use of materialist economic arguments to mount a largely (though not exclusively) textual attack on the neo-colonial form of imperialism. Combination is also evident - as the heading to the second section of this chapter indicates - in the fact that the figures involved were or are political organizers, revolutionary leaders and creative writers, as well as analysts of resistance. It is necessary to retain this sense of combination and complexity, since although there would be a definite utility in identifying groups or individuals by key concepts - saying, for example, that the Subaltern Studies Group focus on peasant or non-nationalist resistance, or that the Caribbean writers studied here privilege mythology and textual resistance - there is a danger in reducing multifaceted activities to a single encapsulating phrase.

Resistance has neither been the work merely of a disorganized rabble (colonial ideology in its dismissive mode), nor that of some vast conspiracy (colonial ideology in its paranoid mode). There have, however, been connections: ideological, tactical and what one might term inspirational. At the inspirational level, one liberation struggle can spark off another: the Vietnamese victory over the French in 1954 was one of the catalysts for the start of the Algerian War of Independence, while the struggle in Guinea-Bissau led by Amilcar Cabral against the Portuguese inspired the May Revolution led by air force officers in Portugal which brought down the Fascist government of Antonio Salazar. At the tactical level, forms of resistance from other countries have been studied and copied, adapted or rejected according to need. (It is worth noting in passing that if resistance has been something of a forgotten subject, then it, too, has its forgotten areas: for instance, it is only relatively recently that attention has been paid to the mundane, non-heroic forms of resistance, as opposed to the more visible or glorious rebellions.) At the ideological or theoretical level, resistance has drawn upon the works of writers from other times and places, and it is on this area that the present chapter will concentrate.

While history as detailed narrative may be excluded from the chapter, history as precedent, as problem, as provocation, is very much present in the work of the different individuals and groups. History is present also in that while detailed events may be lacking, the chapter aims to indicate something of the continuities and breaks from the colonial to the post-colonial period: the fact that Fanon or Gandhi may continue to inspire; the possibility that the post-colonial period requires different modes of resistance or categories of analysis. One of the things which the chapter makes clear is that there is no single phenomenon which one could identify as resistance theory. Rather, theories are capable of being developed specifically for the purposes of resistance or, perhaps especially in a nativist context, theories which were not obviously resistant may be adapted and mobilized for insurgent ends.

Having declared the impossibility of tracing the histories of resistance here, it is still necessary to provide some historical contextualization for the discussions of the writers, focusing on two main areas: the Indian subcontinent and what, following Paul Gilroy, one might usefully call the Black Atlantic. The different emphasis in the contextualizing reflects the different paths and possibilities of resistance in the two areas.

India

As the imperial jewel in the crown, India represented the greatest expenditure of effort at the ideological level by the British. They had the greatest investment in presenting the imperial presence and practices in India in the most favourable light, and it is no coincidence that the example of resistance-as-unwarranted-treachery should come from India. The apparent singularity of 1857, its supposed exceptional status, is also no coincidence, representing as it does a formidable process of historical amnesia and excision of centuries of resistance to the British. In fact, far from being aberrant, 1857 could be regarded as simply the latest and most dangerous in a long series of rebellions, since there had been more than forty major uprisings and possibly hundreds of smaller ones over the course of the preceding century, while the brutal crushing of the rebellion did not bring all resistance to an end.

The variety of forms adopted, the continent-wide spread of outbreaks, the persistence of groups and individuals involved, make Indian resistance remarkable. Ranging from armed rebellion to the non-violent forms of Gandhian satyagraha , it involved at different times all levels of society, from the aristocracy to peasant and tribal groups; its character and aims might be politically progressive or reactionary; its methods could be legal and co-operative, or oppositional and illegal; its dominant ideology might be religious or secular, reformist or revolutionary. Some rebellions were brief and fierce; others, like the Sanyasi uprising in Bengal in the late eighteenth century, lasted for almost forty years.

From the late nineteenth century a number of factors decisively altered the character and direction of resistance in India. These included: the formation of the Indian National Congress in 1885 as a focus for agitation at the national (rather than local or regional) level, and the concomitant development of theories of national independence; the articulation of critiques of imperialism as economically exploitative and socially oppressive (to counter British ideology which portrayed it as enlightened and beneficial); and the development, especially under Gandhis leadership, of strategies which undermined both the moral legitimacy of British rule and areas of political control or economic profitability. In general, though, Congress as a movement was a product of modernity, a bid to enter the realm of the independent nation-state, and to achieve this through the creation of a movement which in Gramscian terminology was fully national-popular (despite British efforts to portray it as a disaffected or disappointed middle-class minority). This was reflected in the steady growth of Congress as a broad-based movement fighting on many fronts, while other forms of resistance which lacked a popular base, such as the revolutionary terrorists in Bengal, came and went relatively rapidly (though the latter did introduce the modern approach of political assassination as terror tactic, and helped to undermine the idea that British control was invincible).