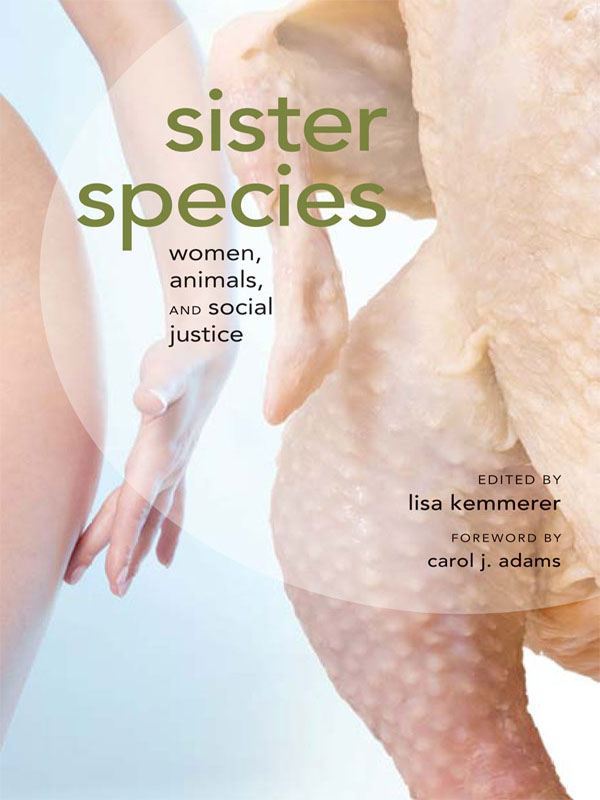

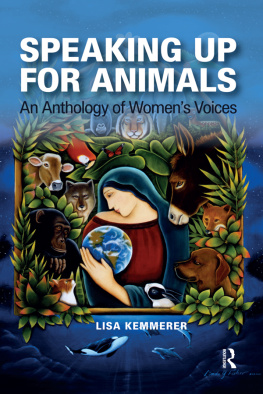

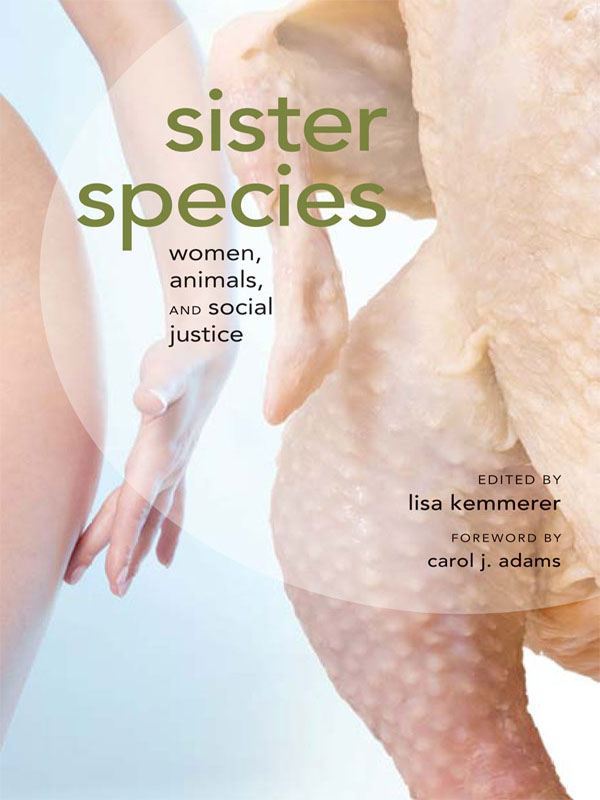

sister species

2011 Lisa Kemmerer

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

1 2 3 4 5 C P 5 4 3 2 1

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Sister species : women, animals and social justice / edited by Lisa A. Kemmerer; foreword by Carol J. Adams.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-252-03617-0 (cloth : alk paper)

ISBN 978-0-252-07811-8 (pbk. : alk paper)

1. Animal welfare. 2. Animal rights. 3. Ethics.

I. Kemmerer, Lisa.

HV4708.S57 2011

179.3dc22 2010050885

dedicated to

those who work across intersections of violencewho put their lived (though perhaps untheorized) knowledge of interlocking oppressions into practice to bring deep-seated change: vegans staffing rape crisis lines, feminists engaged in open rescue, those tending little home sanctuaries while working day jobs to heal battered children, those who speak out against racism while tending shelters for the homeless, and any number of other determined activists who are helping to end oppressions on more than one front.

foreword

carol j. adams

h ow do women, especially feminists, discover the call to be involved in stopping animal suffering and why does it become so profoundly important in the shaping of their activism? How have women influenced the animal advocacy movement even though this influence is not as acknowledged as it might be?

This book provides stories from women involved in animal advocacy that answers these questions. Through their stories, the women establish that the suffering of animals is an important concern for human beings; that womens involvement in animal advocacy is consistent with other traditions of womens social advocacy; and that there are connections among forms of oppression and these connections require that we include animals in our advocacy.

The question is sometimes posed: why do women work for animals instead of women and other disenfranchised humans? The question simplifies a complex dynamic. These compelling stories, in evoking the particular nature of each of the authors work and life, reveal the complexity. By gathering these diverse essays together, Lisa Kemmerer shows us that the either/or approach to social change (work for disenfranchised humans or work for animals) is false. One answer to the question why animals? is that feminism led us here. The here where we find ourselves, at least most of us, does not simplify through opposition (us or them, women or animals). These essayists demonstrate what countless feminist-vegan writers and activists have known for many years now. Activism for justice isnt easily divisible into human and nonhuman.

At this point, with more than thirty-five years of feminist writing and activism that explicitly includes animals,than 60 percent (at the minimum) of animal activistsand women doing the majority of activism, personal stories that tell the how and why of womens involvement are important.

But these personal essays dont just offer insights into why and how women work on behalf of animals. Through their stories, these writers give us the opportunity to learn more about what is happening to animals.

In The Sexual Politics of Meat, I propose that in Western cultures built on the oppression of animals, animals are absent referents. They disappear as individuals or subjects to become someones objectto be bred, exhibited, hunted, devoured. Information about the transformation of a subject into an object is upsetting, discouraging, and depressing; this information can inspire feelings of rage, hostility, anger. This knowledge and these feelings can also be transformed into activism. Read and see how.

One important aspect of these essays is that they show how awareness leads to activism. Awareness does not exist on its own, without its companion, activism.

In terms of my feminist-vegan theory, awareness of the structure of the absent referent and the lives it destroys motivates activists to challenge it, to restore what (actually who) has been made absent. Awareness and engagement exist together. I like the way these personal essays illustrate this point. Many of them reveal a relational ethics that situates the I who speaks as well as the subject this I encounters. They show the refusal of the political structuring of human supremacy; we learn about the process by which an object is restored to subject status.

We all know by this point how the political structures personal lives; what these essays reveal is how we can illumine the political by personal stories. These personal essays anchor the difficult information of animals lives under humans and they offer us a way into thinking about and relating to animals.

There is anger and passion here. How could it be otherwise?

This anger and passion is confusing to people who remain firmly anthropocentric. They ask, Why are you angry about what is happening to animals and not what is happening to humans? (They presume we arent.) Or they ask, why we are doing this rather than feeding the homeless or helping battered women? And we loop back to where we began, with an either/or perspective that thinks we must always be choosing one over the other. This teleological presumption that humans are the fulfillment of evolution (superior to all the other animals), this human exceptionalism, requires that animal activists defend their choices. Of course, I have found that it is only human exceptionalists who believe you cant be doing both. I dont think animal activists need to defend why they have decided to focus in the way they have on animal issues, but illuminating how they came to what they are doing may help those who are put on edge or made slightly defensive when they realize that our activism implicates them. When they realize there are choices to be made, and some of those choices are ones they need to make, will animals remain objects in their lives or not?

As I say in Living Among Meat Eaters, people who benefit from the object status of animals think change is hard. Not changing is even harder. They just havent discovered this yet.

Another thing human exceptionalists often do is to stereotype animal activists by race and class. In this book youll see why this truly is a fundamental error; an error that reveals itself to be a project of anthropocentrism. Stereotyping animal activists arises from biases and misperceptions; it is not representative of animal activism at all. Not only is ethnic and racial diversity represented in this book, but also tactical diversityfrom campaigns originating with the Humane Society of the United States to direct action, from founding a sanctuary to pioneering for animals in higher education, from activism that sexualizes women to activism that critiques activists who sexualize women.

As a result of this diversity, let me advise you not to take anything that any one of these women says as an absolute representation of animal activism. Their differences from one another in situation, tactics, and philosophy not only illustrate the diversity of the movement, they also show that there isnt one way or one voice.

If you assembled us all in a room, there would be energetic discussions and disagreements: about language choice, about the theoretical framing of animal oppression, about tactical decisions, about the use of women in animal activism and the symbolism of womens bodies. It probably wouldnt be cacophonous, but it would be lively (like this anthology). It would reflect the diversity that is central to the purpose of this anthology: To decenter any notion that we can identify just who an animal activist type is.

Next page

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.