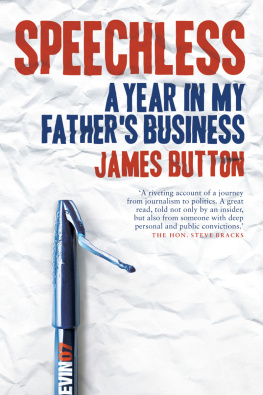

Authors Note

T his book is the result of a childhood in a political family, a working life in journalism, and a mid-career invitation to write speeches for a Labor Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd.

My father, John Button, was a federal minister who had spent a lot of my childhood years away in Canberra. The commentary that followed his death in April 2008, reminded me of his role in helping to run the country during both the Hawke and Keating governments. Now I had a chance to see how it all worked.

From December 2008, I spent sixteen months working in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. During that time the Rudd government faced two huge challenges: the global financial crisis and climate change. The Prime Minister needed to pull the governments response to these problems into a larger story about his government and himself. He needed to distil the essence of his policies and program into spare, compelling speech that connected with ordinary people.

I was inspired to try to help Kevin Rudd tell the story of his governmentand of the countrythrough speechwriting. It did not work out as I had hoped, but I had an extraordinary experience, and gained something I had not expected to: an insight into the public service.

As a speechwritera job poised somewhere between dreams and deliveryI learnt about the practical problems of communicating with a sceptical media and the switched-off public. As a passing Canberra insider, I saw how aspects of both Rudds leadership and the complexities of public policy making were unknown to most of the country. As the son of a former politician, I thought a lot about the impact politics had on him, and on our family. In July 2010, three months after leaving my job and shortly after the fall of Rudd as Prime Minister, I decided to put these experiences into a book.

There are writers whose fierce allegiance is to the story. Tell it all. I admire those writers but I am not one of them. In Canberra I observed other ethical codes at work: loyalty, collegiality, respect for the ministerial office and the secrecy that allows sensitive decisions to be made with confidence. I have tried to navigate these different conceptions of honour, without sacrificing the story.

In one sense, any book that draws on inside information is an ethical breach. Beyond the public services strong prohibitions against disclosure, there is always a time to speak, and a time to be silent. I wrote this book because I feel that an important issue is at stake. Our politics seems thin and barren. Ordinary people are increasingly uncomprehending and disengaged. A friend in his sixties who has followed politics intently, all his life, says he no longer does because it is too dispiriting and dull.

But this view, however understandable and widely felt, does not do justice to the many people I met in Canberra. They are trying to do good things, and often managing to do so, yet sometimes failing for reasons far more complicated and human than the usual explanations that emerge. On the inside, the stories of politics and government are as fascinating and vital as ever. We must find better ways to tell them.

Chapter 1

Would You Want to Die Wondering?

A t the age of ten I ran for election to the Swan Hill Excursion Committee of Hawthorn West Primary School in Melbourne. I was keen to get on this committee. The students voted; Miss OMara counted the papers. Of thirty students, I got thirty votes. That was my downfall.

Miss OMara turned to me, her voice very cold: You voted for yourself, didnt you?

Yes, I piped, I did.

You ought to be ashamed of yourself, she said. Youre off the committee. Go to the back of the room.

I took a desk in the corner and buried my hot face in a book. I was ashamed all right, humiliated. But I was also bewildered. If it was fine to want to be on the committee, why was it wrong to vote to make it happen? Would Gough Whitlam not vote for himself for PM? I came from a political family. I knew the deal. To get ahead, you had to get the numbers.

A year later my parents sent me to a private school, Melbourne Grammar, where many boys had metal smiles and all called me Button. It was a jolt at first, but my young teacher, Steven Shann, was perhaps the most inspiring I ever had. He threw out regular lessons and turned the classroom into a miniature city, with a newspaper, law courts, businesses, a stock exchange, political parties and a parliament that debated issues of the day. I was editor of the 6-S Weekly, my first job in journalism. I was also a judge, and Leader of the Opposition. But it wasnt enough for me.

Elections for Prime Minister were held every two weeks. Near the end of the year, I noted with alarm that only one election remained. My window was closing. I moved a motion in Parliament that two elections be held in the last two weeksto give more kids a go at being PM, I said.

The MPs were not fooled. One told Parliament: Buttons only doing this so he can be Prime Minister.

Nothing of the sort, I protested.

It was everything of the sort. My motion failed. In the election the students smelt a candidate who was a little too hungry for the job, and voted for the other guy. I came second. My political career was over. I was eleven years old.

*

Thirty-six years later, in December 2008, I got a phone call. The measured, authoritative, friendly voice belonged to Terry Moran, head of the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet (or PM&C). Moran had a public servants delicacy but his drift was clear: the Prime Ministers speeches were not going well. Moran said he needed a writer to work with him to help him simplify and lift his prose. He also needed someone to help him shape his narrative and that of the government. A clear writer, engaged with politics and policy, capable of elegant prose and, ideally, with a sense of humour. I dont know how you are with humour, Moran said.

I didnt know either. I didnt know the first thing about speechwriting. For twenty-three years I had been a journalist. Morans unexpected offer was both troubling and tempting.

I havent read your book, Moran continued.

Thats because I havent written it, I said, embarrassed. For three years I had been Europe correspondent for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald. Now I was fiddling with a book based on the London bombings, the French riots, the Danish cartoons and other events I had reported on that raised questions about immigration, national identity and the place of Islam in the West. I knew something about these subjects but to make the book more topical I was trying to relate them to Australia, without much success.

I was also reluctant to go back to my old job at The Age. I didnt want to be another ex-correspondent on the features desk, pining for the glory days overseas. Morans call came at the right time.

But why was I right for the job? The worlds of journalism and politics are so interconnected and intimate, yet so far apart. I felt Moran probing for a bridge, too, when he said: I think the Prime Minister might find a pleasing symmetry in your working for him.

I assumed he was referring to my father, John Button, who had been Industry Minister in the governments of Bob Hawke and Paul Keating. Would Rudd really care about that, I wondered. He had not come to my fathers state funeral in April. This had been interpreted in the media as evidence that Rudd was not a true Labor figure, as this had been a true Labor event. But neither I nor anyone in my immediate family had really minded. He had only known my dad a little.