James Button weaves painful family history into his year spent in Canberra as a frustrated speechwriter to then-PM Kevin Rudd. Subtle, fresh, moving, it ripples with surprises.

Helen Garner, The Age

A beautifully written, personal essay; by turns tender and wise and, when necessary, brutally honest. Above all else, its an offering of love to a father and a brother.

Brett Evans, Inside Story and Canberra Times

A fascinating read, because it connects the lives of this generation of progressives both Greens and Labor with the lives of their parents.

Joel Deane, Australian Book Review

Exceptional ... the most perceptive assessment of the Australian public service that Ive come across: an inside account written by an outsider.

Peter Shergold, former head of the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, The Conversation and Canberra Times

Button evinces genuine admiration for the competence and dedication of the boffins who have co-opted him.

Amanda Lohrey, The Monthly

James Button worked in 2009 as a speechwriter to the then Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd. He was previously Europe Correspondent for The Age and The Sydney Morning Herald. He is a former deputy editor and opinion editor of The Age, and has won two Walkley Awards for feature writing. He lives in Melbourne with his wife, May, and children Harry and Lola.

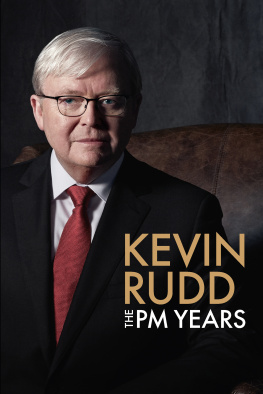

SPEECHLESS A YEAR IN MY FATHERS BUSINESS

JAMES BUTTON

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

An imprint of Melbourne University Publishing Limited

Level 1, 1115 Argyle Place South, Carlton, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 2012

Reprinted (twice), 2012

Reprinted 2013

This edition printed 2013

Text James Button, 2012

Design and typography Melbourne University Publishing Limited, 2011

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publishers.

Every attempt has been made to locate the copyright holders for material quoted in this book. Any person or organisation that may have been overlooked or misattributed may contact the publisher.

Text design by Patrick Cannon

Cover design by Design By Committee

Typeset in Bembo 12.5/15.5pt by Cannon Typesetting

Printed in Australia by McPhersons Printing Group

Cataloguing in Publication data available from the

National Library of Australia

ISBN 9780522864397 (pbk.)

ISBN 9780522864724 (epub.)

CONTENTS

AUTHORS NOTE

T HIS BOOK IS the result of a childhood in a political family, a working life in journalism, and a mid-career invitation to write speeches for a Labor Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd.

My father, John Button, was a federal minister who had spent a lot of my childhood years away in Canberra. The commentary that followed his death in April 2008, reminded me of his role in helping to run the country during both the Hawke and Keating governments. Now I had a chance to see how it all worked.

From December 2008 I spent sixteen months working in the Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet. During that time the Rudd government faced two huge challenges: the global financial crisis and climate change. The Prime Minister needed to pull the governments response to these problems into a larger story about his government and himself. He needed to distil the essence of his policies and program into spare, compelling speech that connected with ordinary people.

I was inspired to try to help Kevin Rudd tell the story of his governmentand of the countrythrough speechwriting. It did not work out as I had hoped, but I had an extraordinary experience, and gained something I had not expected to: an insight into the public service.

As a speechwritera job poised somewhere between dreams and deliveryI learnt about the practical problems of communicating with a sceptical media and the switched-off public. As a passing Canberra insider, I saw how aspects of both Rudds leadership and the complexities of public policy making were unknown to most of the country. As the son of a former politician, I thought a lot about the impact politics had on him, and on our family. In July 2010, three months after leaving my job and shortly after the fall of Rudd as Prime Minister, I decided to put these experiences into a book.

There are writers whose fierce allegiance is to the story. Tell it all. I admire those writers but I am not one of them. In Canberra I observed other ethical codes at work: loyalty, collegiality, respect for the ministerial office and the secrecy that allows sensitive decisions to be made with confidence. I have tried to navigate these different conceptions of honour, without sacrificing the story.

In one sense, any book that draws on inside information is an ethical breach. Beyond the public services strong prohibitions against disclosure, there is always a time to speak, and a time to be silent. I wrote this book because I feel that an important issue is at stake. Our politics seems thin and barren. Ordinary people are increasingly uncomprehending and disengaged. A friend in his sixties who has followed politics intently, all his life, says he no longer does because it is too dispiriting and dull.

But this view, however understandable and widely felt, does not do justice to the many people I met in Canberra who are trying to do good things, and often managing to do so, yet sometimes failing for reasons far more complicated and human than the usual explanations that emerge. On the inside, the stories of politics and government are as fascinating and vital as ever. We must find better ways to tell them.

CHAPTER 1

WOULD YOU WANT TO DIE WONDERING?

A T THE AGE of ten I ran for election to the Swan Hill Excur sion Committee of Hawthorn West Primary School in Melbourne. I was keen to get on this committee. The students voted; Miss OMara counted the papers. Of thirty students, I got thirty votes. That was my downfall.

Miss OMara turned to me, her voice very cold: You voted for yourself, didnt you?

Yes, I piped, I did.

You ought to be ashamed of yourself, she said. Youre off the committee. Go to the back of the room.

I took a desk in the corner and buried my hot face in a book. I was ashamed all right, humiliated. But I was also bewildered. If it was fine to want to be on the committee, why was it wrong to vote to make it happen? Would Gough Whitlam not vote for himself for PM? I came from a political family. I knew the deal. To get ahead, you had to get the numbers.

A year later my parents sent me to a private school, Melbourne Grammar, where many boys had metal smiles and all called me Button. It was a jolt at first, but my young teacher, Steven Shann, was perhaps the most inspiring I ever had. He threw out regular lessons and turned the classroom into a miniature city, with a newspaper, law courts, businesses, a stock exchange, political parties and a parliament that debated issues of the day. I was editor of the