This paperback edition includes corrections to the hardcover published in March 2008, of which the following are the most significant: I mistakenly reported that Levi Allens trial testimony confirmed that Jim Hadnot had been shot by his own men at Colfax (page 167). Actually, that confirmation came from witness Martin Johns. The white women allegedly raped during the roundup of Colfax suspects were not the sister and niece of Thomas Montfort Wells; they were his wifes aunt and cousin (page 148). The massacre of black men at Hamburg, South Carolina, occurred on July 8, 1876, not July 4 (page 247). Professor Charles Fairmans book about the Supreme Court during Reconstruction appeared in 1987, not 1989. He died in 1988, not 1991 (page 263).

Since this books publication, fragmentary official transcripts of testimony at the first Colfax Massacre trial have come to my attention. (They are in the National Archives in Washington: Records of the Select Committee on that part of the Presidents Message relating to the Late Insurrectionary States, HR43A-F31.4.) Hastily scribbled and clearly incomplete, these statements by Theodore W DeKlyne, William Wright, and Benjamin Brim generally match the New Orleans Republican transcripts upon which I relied. But the transcript of Brims testimony does not include his statementrecorded by the Republican that Christopher Columbus Nash tried to stop his men from shooting one another as they fired at blacks fleeing the burning courthouse. Given the official transcripts imperfections, however, I continue to rely on the newspaper for this point. The fact that Jim Hadnot and Sidney Harris were indeed shot by their own comrades is amply supported by other sources.

I had never heard of the bloody events of April 13, 1873, in Colfax, Louisiana, until 2003, when I read a remarkable travelogue in the Atlantic by the journalist Richard Rubin. Rubin had visited Colfax while doing some research and stumbled upon the historical marker commemorating the riot. His article, based on readings in the local library and conversations with residents, intriguingly sketched the story but left me intensely curious. I soon learned that the Colfax Massacre was not only a dramatic spasm of local violence but a pivotal event in the political and constitutional history of post-Civil War America.

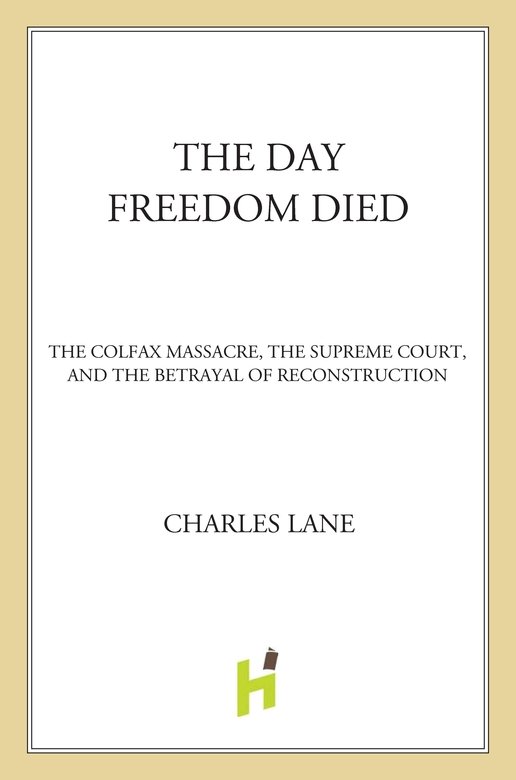

I could not have written this book without a lot of help. I would first like to thank my college classmate, Jonathan G. Cedarbaum, for insisting that I should do that book about Cruikshank even at a time when I wasnt 100 percent serious about it myself. The next crucial booster was my literary agent, Scott Waxman, whose confidence got the project off the ground and whose enthusiasm helped sustain it through the inevitable tribulations. I consider Scott a full partner in the effort, along with my editor at Henry Holt, George Hodgman, whose skill and wisdom are, I hope, reflected on every page. George worked very hard to make me a better writer(no small task), and Ill always be grateful to him. Editors David Patterson and Kenn Russell, also of Henry Holt, shepherded the book through the final production process with skill and care. Patrick Clark lent much-needed assistance with the footnotes and many other things. Vicki Haire copy-edited brilliantly.

Thanks are due to my then boss at the Washington Post, Assistant Managing Editor Liz Spayd, for granting me a six-month book-writing leave in November 2006. (Thanks also to her predecessor, Jackson Diehl, who hired me to cover the Supreme Court, one of the best breaks I ever got.) Others at the Post, including Executive Editor Leonard Downie, Editorial Page Editor Fred Hiatt, Michael J. Abramowitz, Lynda Robinson, David Von Drehle, Marc Fisher, Laura Blumenfeld, Kevin Merida, Michael Fletcher, Keith Alexander, and Benjamin Wittes, offered counsel and encouragement. A former Post colleague, Glenn Frankel, now at Stanford University, pitched in with some well-taken writing advice early on.

I did most of my work in a quiet, comfortable scholars study at the Edward Bennett Williams Law Library of the Georgetown University Law Center. For this marvelous little sanctuary I am indebted to Dean Alex Aleinikoff and Professor Randy Barnett, who spontaneously offered it to me for no reason other than their generous desire to support my project. Matt Ciszek graciously made sure that I had all the books and equipment I needed while working at the library. Erin Rahne Kidwell helped me find what I was looking for in the librarys rare book collection.

I am deeply grateful to Professor James K. Hogue of the University of North Carolina-Charlotte, an innovative scholar who has been, for me, a font of knowledge and analysis on nineteenth-century politics and political violence in Louisiana. His detailed comments on several drafts of the book were worth gold. I also wish to thank Professor Jonathan Lurie of Rutgers University for reviewing several draft chapters. Other helpful advice came from John Donvan, Jason Zengerle, Ross Davies, Baruch Weiss, Graham Hodges, J. Morgan Kousser, Gary Gerstle, John Barrett, Michael Ross, Robert J. Kaczorowski, Ted Tunnell, and R. Thomas Howell.

When I had specific legal questions, I turned to Walter Dellinger, Miguel A. Estrada, Paul A. Engelmayer, Akhil Amar, and Erwin Chemerinsky. Stephen Hal-brook provided me with invaluable copies of the New Orleans press coverage of the Grant Parish cases. Professor Michael J. Glennon of the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy at Tufts University, my uncommonly wise mentor on constitutional law, took the time to read a draft of the book and gave freely of his expertise.

Willie Calhouns descendant, Tybring Hemphill of Victoria, B.C., was a marvelous source of information about his familys illustrious history, and I am deeply indebted to him. Dr. David G. Borenstein of Arthritis and Rheumatism Associates of Washington, D.C., Philip M. Teigen of The National Library of Medicine in Bethesda, Maryland, and George Wunderlich, executive director of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland, provided answers to my questions about the diagnosis and treatment of disease and injuries in the nineteenth century. Professor Eliot A. Cohen of the Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies chipped in with some key Civil War facts. Clark Doc Hawley of New Orleans was generous with his knowledge of Louisianas glorious steamboat history, as were Professors Carl A. Brasseaux of the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and Paul Paskoff of Louisiana State University. On the history of Cazenovia, New York, I called on Russell Grills and Judge Hugh Humphreys. Kater Hake of Cotton Incorporated helped with agricultural history.

Not even Hurricane Katrina was powerful enough to diminish the energy and good humor of my New Orleans-based researcher, Melissa Smith, who was resourceful and efficient as she hunted down obscure documents in the Crescent Citys storm-ravaged archives and libraries. Judy Riffel did the same with equal aplomb in Baton Rouge. Professors Michael Gerhardt of the University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill Law School and Douglas A. Berman of the Moritz College ofLaw at Ohio State University rummaged through the libraries of their respective universities and found much-needed texts I could not have gotten otherwise.

In researching this book, I spent many hours in archives and libraries, coming away not only with information but also with a new appreciation for the work that these institutions do. Without exception, I found staffers at the National Archives in Washington, D.C., and College Park, Maryland, the Library of Congress, the Louisiana State Archives, and Louisiana State Universitys library system to be informed, helpful, and politeeven if in many cases I never learned their names. Special mention is due Fred Romanski and Trevor Plante of the National Archives, Barbara Gusky and Bill Stafford of the Louisiana State Archives, Phyllis Kinnison of LSU, and Mariam Touba of the New York Historical Society.