ALSO BY ALAN GOVENAR

NONFICTION

The Early Years of Rhythm and Blues

Stoney Knows How: Life as a Sideshow Tattoo Artist

Masters of Traditional Arts: A Biographical Dictionary

African American Frontiers: Slave Narratives and Oral Histories

Portraits of Community: African American Photography in Texas

Deep Ellum and Central Track (with Jay F. Brakefield)

American Tattoo

Meeting the Blues: The Rise of the Texas Sound

Flash from the Past: Classic American Tattoo Designs, 1890-1965 (with D. E. Hardy)

A Joyful Noise: A Celebration of New Orleans Music (with Michael P. Smith)

Living Texas Blues

FOR YOUNG READERS

Extraordinary Ordinary People: Five American Masters of Traditional Arts

Stompin' at the Savoy: The Norma Miller Story

Osceola: Memories of a Sharecropper's Daughter

ESSAY COLLECTIONS

Juneteenth Texas: Essays in African American Folklore

(with Francis E. Abernethy and Patrick B. Mullen)

ARTIST BOOKS

For Boys Who Dream of War

Daddy Double Do Love You

Cold Earth

Midnight Song

The Blues and Jives of Dr. Hepcat

Casa di Dante

The Light in Between

The Life and Poems of Osceola Mays

Paradise in the Smallest Thing

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The journey that shaped this book began more than a decade ago when I was asked in 1994 by Lonn Taylor and Nianni Kilkenny to develop a public program at the National Museum of American History on African American cowboys. Subsequent presentations of that program at the Festival de Printemps in Lausanne, Switzerland, the National Black Arts Festival in Atlanta, and Colorado College in Colorado Springs refined my understanding of the questions often engendered by discussions of the migratory patterns of African Americans. Adrienne Seward and Sterling Stuckey suggested that I rethink existing literature on the American frontier, and Paul Stewart, Ottawa Harris, and Nudie Williams introduced me to the collections of the Black American West Museum and Heritage Center in Denver.

My involvement in the International Conference on African American Music and Europe at the Sorbonne in 1996, organized by Michel Fabre and Henry Louis Gates Jr., expanded the scope of my inquiry and provided me an opportunity to speak with Paul Oliver and Francis Hof-stein about misconceptions of African American culture in southern and western regions of the United States.

In 1999, Saul Bellow, after an intense conversation about Ralph Ellison and race relations in America, urged me to contact his son, Adam, who was intrigued by my efforts and later introduced me to Janet Hill. Over the years, my dialogue with Janet, which began with her interest in publishing an updated edition of my book African American Frontiers, encouraged me to create a substantially new work through the arduous process of revision.

Clyde Milner II, who invited me to participate in a panel he assembled for the 2005 national meeting of the Organization of American Historians in San Jose, broadened my perspective on the idea of the frontier and compelled me to reexamine the fundamental premise from which my work advanced.

Kim Gandy, president of the National Organization for Women, recommended new interview subjects. John Slate assisted me in surveying historical archives across the country. Marlene Chavis graciously provided her interview with Josephine Harreld Love. Jay Brakefield transcribed many of my interviews, often checking facts and dates. Alan Hatchett helped in the preparation of the photographs for publication.

My wife, Kaleta Doolin, shared her insights as the final conceptualization of this book emerged. Tara Neal, Amanda Campbell-Wyatt, and my daughter, Breea Govenar, aided in the organization of references and primary source materials. My son, Alex Govenar, challenged me with his thoughts on the interplay of cultures in music and film, and inspired me to delve more deeply into the unexpected stories of people I heard for the first time.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Not in word alone shall freedom's boon be ours.

from to miss mary britton by paul laurence dunbar

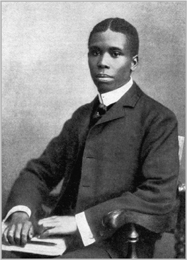

Paul Laurence Dunbar, ca. 1895.

PAUL LAURENCE DUNBAR'S POEM To Miss Mary Britton was first published in 1893 in his collection Oak and Ivey, the same year that Frederick Jackson Turner delivered his paper The Significance of the Frontier in American History to the American Historical Association in Chicago. Dunbar had traveled to Chicago that year, too, carrying copies of his Oak and Ivey, hoping to sell them for one dollar a copy at the World Columbian Exposition, the first World's Fair. Needless to say, Turner and Dunbar never met each other. In fact, they lived worlds apart.

While Turner proclaimed, The frontier has gone and with its going has closed the first period in American history,a different America, where God might speed the happy day/When waiting ones may see/The glory-bringing birth of our real liberty. The term frontier, Turner said, is an elastic one, and for our purposes does not need sharp definition, but he did affirm the position of the United States census director in offering one concrete definition: The frontier was a place occupied by fewer than two people per square mile. The frontier, Turner observed, marked the divide between civilization and savagery, and taming the frontier helped to shape such values of the American citizen as personal independence and participatory governance. Furthermore, the advance of American settlement westward onto free land explained not only the development of the United States but also American democracy and the nation's character. The wilderness masters the colonist, wrote Turner, giving him a buoyancy and exuberance which comes with freedom. Certainly, African Americans in 1893 did not enjoy such freedom. Though they had been emancipated from slavery, Reconstruction had ended and racism was rampant. Dunbar, in the published introduction to his poem To Miss Mary Britton, extols the virtues of a schoolteacher who protested in a ringing speech against the passage of a separate coach bill in Kentucky. Her action, Dunbar said, was heroic, though it proved to be without avail.

Though little is known about the life of Mary Britton, a similar protest by Homer Adolph Plessy two years later, in 1895, triggered a landmark court case that became the basis for legalized segregation nationwide. After Plessy sat in the white section of an East Louisiana Railroad train car, a conductor confronted him and ordered him to leave. When he refused, he was arrested and jailed in New Orleans, charged with violating a recently enacted law mandating separate seating for coloreds. Plessy was light-skinned and only one-eighth African American, but Louisiana applied the one drop rule, meaning that anyone with one drop of nonwhite blood was by definition colored.