Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Govenar, Alan B., 1952

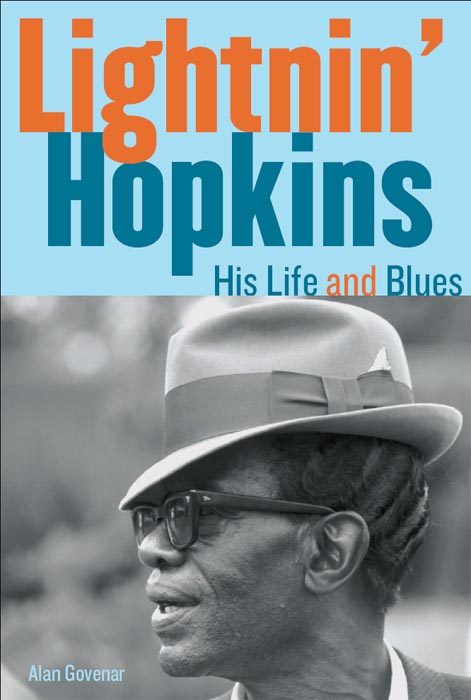

Lightnin Hopkins : his life and blues / Alan Govenar.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-55652-962-7 (hardcover)

1. Hopkins, Lightnin, 1912-1982. 2. Blues musiciansUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

ML420.H6357G68 2010

781.643092dc22

[B]

2009048798

Interior design: Jonathan Hahn

2010 by Alan Govenar All rights reserved

Published by Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-55652-962-7

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

Contents

Acknowledgments

W riting this book spread over more than fifteen years. While there were days and months that I set the manuscript aside, I knew Id come back to it and complete what I had set out to do. The amount of inaccurate information on Lightnin Hopkins made me especially vigilant, and numerous people helped me through the arduous process of establishing a cohesive biography.

Andrew Brown propelled my work forward by sharing his voluminous research and then reading and critiquing several drafts of the manuscript. Chris Strachwitz of Arhoolie Records made available his archive and record collection, and my frequent conversations with him clarified many inconsistencies. Jane Phillips, whom I first talked to more than a decade ago, made valuable suggestions as she shared her memories of Lightnin during the 1960s. David Benson openly discussed Lightnins day-to-day life during his last years. Paul Oliver and Pat Mullen aided me in contextualizing the cross-cultural appeal of Lightnins blues. Laurent Danchin translated various articles published in French and engaged me in a dialogue I had not foreseen.

I am also grateful to Les Blank of Flower Films, Jeff Place of the Smithsonian Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, John Wheat of the Center for American History at the University of Texas, Dan Morgenstern of the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers University, Bill Belmont of Prestige Music Archives/Concord Music Group, and many others who offered their assistance, including Sam Charters, Mack McCormick, Paul Oliver, Roger Armstrong, Barbara Dane, David Evans, Kip Lornell, John Broven, Ed Pearl, Bernie Pearl, Carroll Peery, Bruce Bromberg, Paul Drummond, Jay Brakefield, Stan Lewis, Don Logan, Joe Kessler, Eric Davis, Eric LeBlanc, Andre Hobus, Krista Balatony, Ray Dawkins, Clyde Langford, Alan Hatchett, Francis Hofstein, Norbert Hess, and Alan Balfour.

My wife, Kaleta Doolin, and my children, Breea and Alex, were a constant source of encouragement as my efforts moved forward, bringing a counterpoint to my work that has enriched my life.

Introduction

I been making up songs all my life. I could get out among people cause this heres a gift to me. An old lady told me, Son, your mother had music in her heart when she was carrying you. You know what that mean, dont you? When I come into this world I was doin this.

S am Lightnin Hopkins, at the time of his death in 1982, may have been the most frequently recorded blues artist in history. He was a singular voice in the history of the Texas blues, exemplifying its country roots but at the same time reflecting its urban directions in the years after World War II. His music epitomized the hardships and aspirations of his own generation of African Americans, but it was also emblematic of the folk revival and its profound impact upon a white audience.

What distinguished Lightnin Hopkins was his virtuosity as a performer. He soaked up what was around him and put it all into his blues. He rambled on about anything that came into his mind: chuckholes in the road, gossip on the street, his rheumatism, his women, and the good times and bad men he met along the way. In his songs he could be irascible, but in the next verse he might be self-effacing. He prided himself on his individuality, even if it meant he was full of inconsistencies. He often poured out his feelings in his songs with a heart-wrenching pathos, but it could be hard to tell if he was truly sincere. He peppered his lyrics with few actual details about his own life, but he was at once raw, mocking, extroverted, sarcastic, and deadly serious. Most of the time, Lightnin appeared to trust no one, yet he knew how to endear himself to his audience. While he voiced the hardships, yearnings, and foibles of African Americans in the gritty bump and grind of the juke joints of Third Ward Houston, he could be cocky and brash in his performances for white crowds at the Matrix in San Francisco, or at the New Orleans Jazz and Heritage Festival, or a concert hall in Europe, where he was in complete control and was adored.

Lightnins down-home blues did not adhere strictly to a traditional, three-line, AAB verse form, but rather he improvised a form that suited the song he was singing or composing on the spot and expressed what he was feeling at that moment. If Lightnin held a line for one or two extra beats, if he abbreviated the musical time between lines, or if he lost his place during an instrumental riff, he was never fazed. But this is what made it so difficult for bassists and drummers to play with him, and his timing got more erratic as the years went by. He wasnt schooled in the complex harmonic structures and precision of rhythm and blues, but instead stayed with a basic three-chord (tonic, subdominant, dominant) guitar pattern to accompany his vocal phrasing. In doing so, his vocal lines did not always agree metrically with his guitar lines. But for Lightnin the basis of his songs was rarely structure. It was the essence of the blues that he was after. I come along, long about the time that the people first put the blues on this earth for the people to go by, Lightnin said. Well, Im one in the number and the rest of them is dead and gone. I got in that number at a young age and I just keeps it up cause the blues is something that the people cant get rid of. And if you ever have the blues, remember what I tell you. Youll always hear this in your heart: Thats the blues.

Lightnin played both acoustic and electric guitars and was steeped in the Texas country blues tradition. From Blind Lemon Jefferson and Alger Texas Alexander, Lightnin absorbed stylistic and repertoire elements that included a melismatic singing style rooted in the field holler, mixing long-held notes with loose, almost conversational phrasing. Musically, Short Haired Woman, which Lightnin recorded for the first time around May 1947, established the signature sound that he used in just about every song, whether it was a fast instrumental boogie/shuffle or a slow blues. In his guitar playing Lightnin had an open and fluid style with his right hand, using a thumb pick and his index finger. He kept his right hand loose so he could move from playing sharp notes near the bridge to playing wider open chords up near the fingerboard.

Lightnin usually tuned his guitar in the key of E, though not necessarily to a concert pitch. He utilized what ZZ Top guitarist Billy Gibbons has called that turnaround. Its a signature lick. Hed come down from the B chord and roll across the top three strings in the last two bars. Hed pull off those strings to get a staccato effect, first hitting the little open E string then the 3rd fret on the B string and the 4th fret of the G string. He would then resolve on the V chord after doing his roll. Its a way to immediately identify a Lightnin Hopkins tune.

Next page

![Alan Govenar [Alan Govenar] - Lightnin Hopkins](/uploads/posts/book/45858/thumbs/alan-govenar-alan-govenar-lightnin-hopkins.jpg)