Table of Contents

Guide

Page List

SELECT TITLES IN GENDER, CULTURE, AND POLITICS IN THE MIDDLE EAST

Arab and Arab American Feminisms: Gender, Violence, and Belonging

Rabab Abdulhadi, Evelyn Alsultany, and Nadine Naber, eds.

Arab Family Studies: Critical Reviews

Suad Joseph, ed.

Gendering the Middle East: Emerging Perspectives

Deniz Kandiyoti, ed.

Masculine Identity in the Fiction of the Arab East since 1967

Samira Aghacy

Mihr Hatun: Performance, Gender-Bending, and Subversion in Ottoman Intellectual History

Didem Havliolu

Off the Straight Path: Illicit Sex, Law, and Community in Ottoman Aleppo

Elyse Semerdjian

Resistance, Repression, and Gender Politics in Occupied Palestine and Jordan

Frances S. Hasso

Resistance, Revolt, and Gender Justice in Egypt

Mariz Tadros

Copyright 2019 by Syracuse University Press

Syracuse, New York 13244-5290

All Rights Reserved

First Edition 2019

19 20 21 22 23 24 6 5 4 3 2 1

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

For a listing of books published and distributed by Syracuse University Press, visit www.SyracuseUniversityPress.syr.edu.

ISBN: 978-0-8156-3592-5 (hardcover) 978-0-8156-3603-8 (paperback) 978-0-8156-5449-0 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Control Number 2018051310

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dedicated to

Daisaku Ikeda

Contents

Illustrations

Acknowledgments

EVERY LINE OF THIS BOOK was dependent on the seen and unseen efforts of others. I would first like to thank Professor Omnia El Shakry, who provided essential feedback and critical insight in the early stages of this book. At UCLA, I would also like to acknowledge the late Professor Hossein Ziai, whose untimely death saddened his many loyal students. In all my years at UCLA, I took more courses with Professor Ziai than anyone else. I fondly remember during my first quarter at UCLA his stern insistence that I study the Samanids more seriously, and his patient guidance through difficult philosophical texts in Persian. He had the perfect balance of calm intimidation and warm compassion to motivate his students when we needed it most. The Americanist Professor Ellen Dubois was the inspiration behind my transnational approach to Iranian history. She taught me through her own example how to involve every student in a seminar, listen to them and value their contributions. She was a much needed feminist presence in my graduate life. Finally, with mixed emotions I acknowledge the intellectual influence and support of Professor Gabriel Piterberg, who agreed to leave UCLA following a university investigation into allegations of unwelcome sexual advances. While I stand with all victims of sexual harassment and assault, my work benefited from his teaching and guidance.

Several chapters were reviewed by my dear friend and colleague Professor Peter Park. Dr. Roland Lardinois and Dr. Amir Moezzi in Paris also made very helpful suggestions during my research fellowship at the cole des Hautes tudes en Sciences Sociales (HESS) in 2006. The late Iraj Afshar, one of the most prolific editors of modern Iranian historical sources, pointed me to many useful primary sources on the interwar period during my time in Tehran. A number of booksellers, librarians at the University of Tehran, and staff at private research institutes, also offered me alternatives to the difficult labyrinth of obtaining permission to access public facilities as a foreign researcher.

My dedication to Iranian history was sparked by a chance meeting with Maryam Ghaemmaghami, whom I befriended during an English literature class at De Anza College in Cupertino in 1991. After the 1979 revolution, teachers were heavily monitored by government officials and were expected to indoctrinate students with Islamist principles. In this climate, the precocious young Maryam couldnt suppress her natural curiosity to ask challenging questions, and her parents decided to move from Iran to San Jose. It was Maryam who first introduced me to Persian language and culture, which became the starting point for a quest of nearly three decades.

I would also like to thank all of my Persian language instructors who prepared me to do research, especially during times when I could not obtain a visa or it was not safe to visit Iran. The distinguished list of teachers includes Mrs. Behjat Dehqan at the Middle East Institute in Washington, DC, Professors John Perry, Heshmat Moayyad, and Lily Ayman at the University of Chicago, my language instructors at the Dehkhoda Language Institute in Tehran, the San Diego State University team of Persian language instructors, Professor Hossein Ziai and Firoozeh Papan-Matin at UCLA, and my Advanced Persian Language and Tajik instructors in Dushanbe, Tajikistan. I also owe a debt of gratitude to my Iranian friends who taught me to speak PersianRay, Max, Narges, Marcel, Shawn, and many others. I thank my mother and father-in-law, Gila and Ehsan Anooshahr, who have also helped me acquire a better command of spoken Persian by providing a language laboratory in my own living room. Finally, I am grateful to my Iranian host family, the Alavis, who welcomed me in their home in 1998 and gave me the most meaningful immersion and cultural experience.

During the end of this project I had the pleasure of teaching many capable students at the University of California, Davis, especially those who took my seminar on Gender and Sexuality in Modern Iran. Several of my queer-identified students have raised my awareness about the importance of learning from new generational perspectives. In addition, I would like to thank Professors Suad Joseph and Baki Tezcan for giving me opportunities to present my work and develop my teaching in the Middle East/South Asia program.

In the last phases of this book during my time at UCD, my right eye was damaged in a sports incident, making it harder to read for long periods of time, since I was born legally blind in my left eye. I would like to thank Syracuse University Press for allowing me to take breaks and extend my timetable, especially editor-in-chief Suzanne Guiod and all the members of her staff. In addition, in the final phases of the manuscript my anonymous review editors pushed me to engage more scholarly criticism and develop my argument much further. Without their feedback this project would not have developed to this point. Any shortcomings in this book are mine alone.

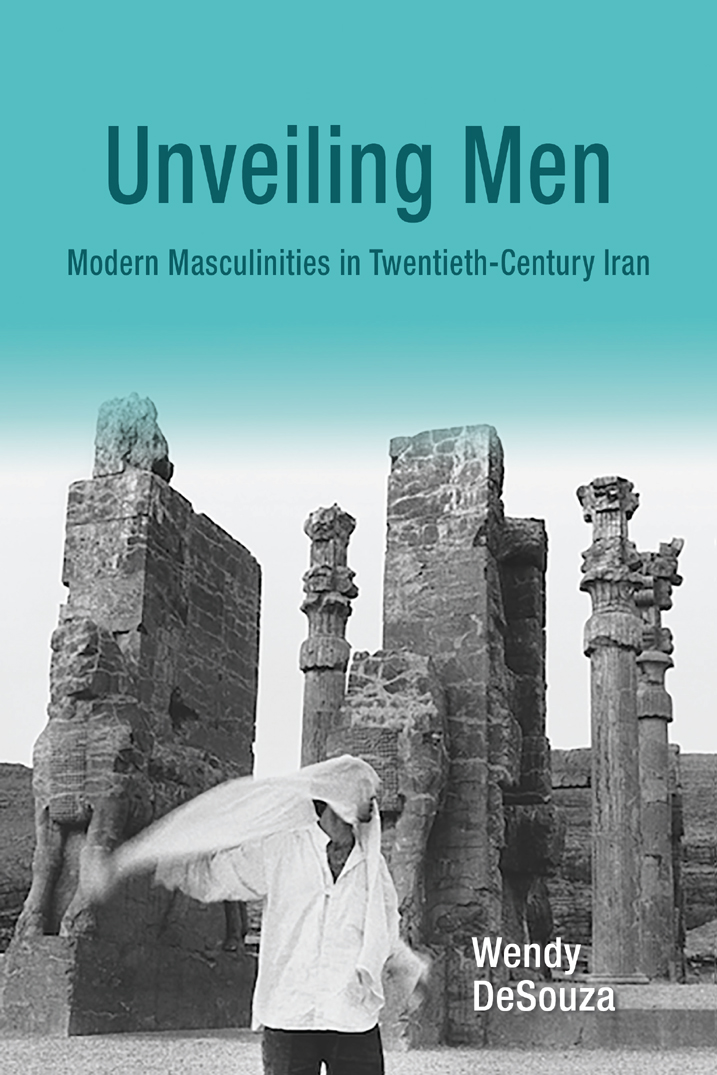

Throughout this book, I cite individuals whose work helped me to think beyond the field of Iranian studies and employ gender and sexuality as categories of analysis to address transnational questions. Their brilliant findings and theoretical approaches guided my journey, which started as a project on European translation of mystical Persian poetry, and later developed to include the problem of nationalism and gender oppression. I owe everything to their revolutionary research. In addition, I would like to extend my heartfelt appreciation to Ghassem Tirafkan, the brother of the late Sadegh Tirafkan, who granted me permission to use the cover image, as well as Andrea Fitzpatrick, who made this connection possible. The world lost a great artist in Sadegh Tirafkan, a person whose work subverts masculinity through empathy and compassion, and I am humbled to honor him in this way.