The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I dedicate this book to my grandchildren, Tariq, Idris, and Nur, all born in the twenty-first century, who will hopefully see the end of this hundred years war

We are a nation threatened by disappearance.

For a few years during the early 1990s, I lived in Jerusalem for several months at a time, doing research in the private libraries of some of the citys oldest families, including my own. With my wife and children, I stayed in an apartment belonging to a Khalidi family waqf, or religious endowment, in the heart of the cramped, noisy Old City. From the roof of this building, there was a view of two of the greatest masterpieces of early Islamic architecture: The shining golden Dome of the Rock was just over three hundred feet away on the Haram al-Sharif. Beyond it lay the smaller silver-gray cupola of the al-Aqsa Mosque, with the Mount of Olives in the background. In other directions one could see the Old Citys churches and synagogues.

Just down Bab al-Silsila Street was the main building of the Khalidi Library, which was founded in 1899 by my grandfather, Hajj Raghib al-Khalidi, with a bequest from his mother, Khadija al-Khalidi.

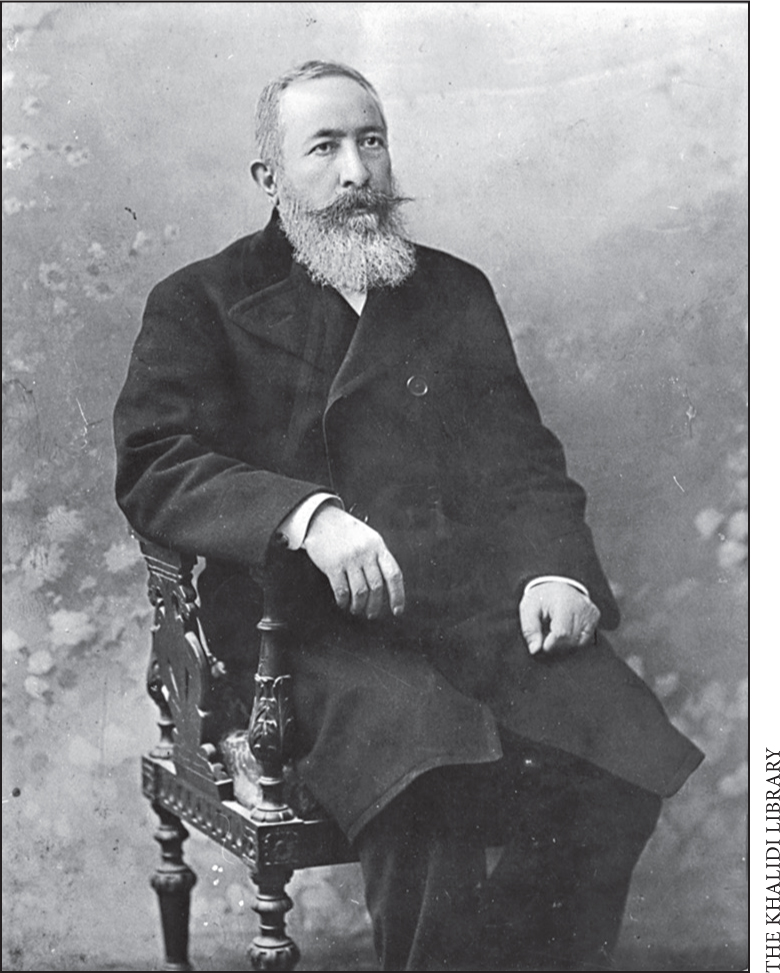

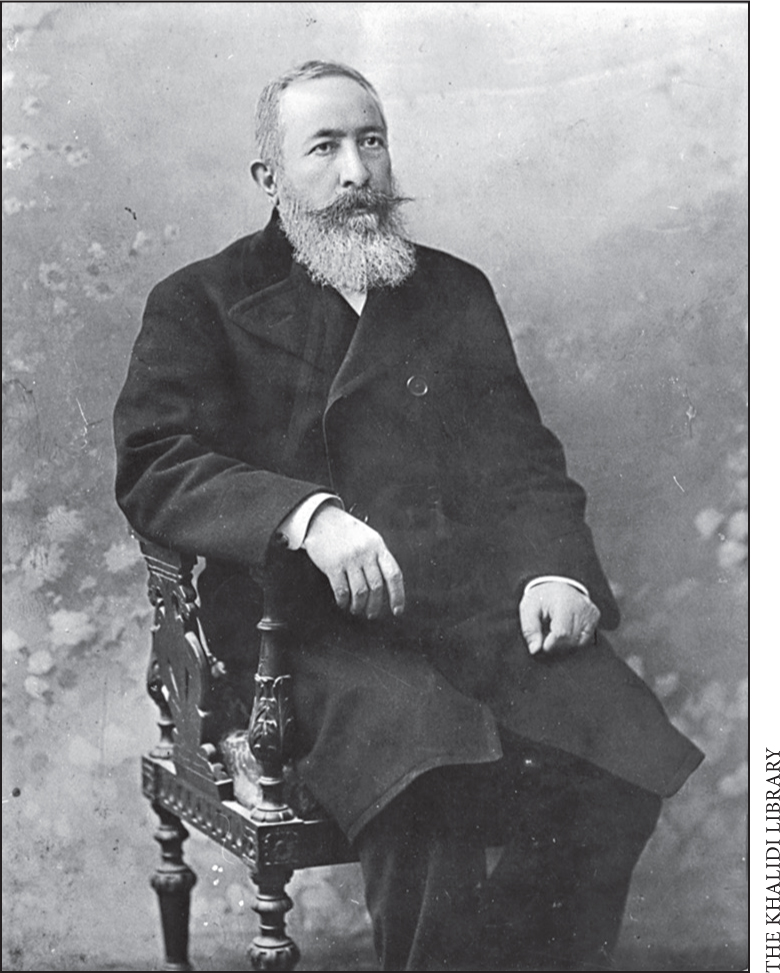

At the time of my stay, the main library structure, which dates from around the thirteenth century, was undergoing restoration, so the contents were being stored temporarily in large cardboard boxes in a Mameluke-era building connected to our apartment by a narrow stairway. I spent over a year among those boxes, going through dusty, worm-eaten books, documents, and letters belonging to generations of Khalidis, among them my great-great-great uncle, Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi. Through his papers, I discovered a worldly man with a broad education acquired in Jerusalem, Malta, Istanbul, and Vienna, a man who was deeply interested in comparative religion, especially in Judaism, and who owned a number of books in European languages on this and other subjects.

Yusuf Diya was heir to a long line of Jerusalemite Islamic scholars and legal functionaries; his father, al-Sayyid Muhammad Ali al-Khalidi, had served for some fifty years as deputy qadi and chief of the Jerusalem Sharia court secretariat. But at a young age Yusuf Diya sought a different path for himself. After absorbing the fundamentals of a traditional Islamic education, he left Palestine at the age of eighteenwithout his fathers approval, we are toldto spend two years at a British Church Mission Society school in Malta. From there he went to study at the Imperial Medical School in Istanbul, after which he attended the citys Robert College, recently founded by American Protestant missionaries. For five years during the 1860s, Yusuf Diya attended some of the first institutions in the region that provided a modern Western-style education, learning English, French, German, and much else. It was an unusual trajectory for a young man from a family of Muslim religious scholars in the mid-nineteenth century.

Having obtained this broad training, Yusuf Diya filled various roles as an Ottoman government officialtranslator in the Foreign Ministry; consul in the Russian port of Poti on the Black Sea; governor of districts in Kurdistan, Lebanon, Palestine, and Syria; and mayor of Jerusalem for nearly a decadewith stints teaching at the Royal Imperial University in Vienna. He was also elected as the deputy from Jerusalem to the short-lived Ottoman parliament established in 1876 under the empires new constitution, earning Sultan Abd al-Hamids enmity because he supported parliamentary prerogatives over executive power.

Yusuf Diya al-Din Pasha al-Khalidi

In line with family tradition and his Islamic and Western education, al-Khalidi became an accomplished scholar as well. The Khalidi Library contains many books of his in French, German, and English, as well as correspondence with learned figures in Europe and the Middle East. Additionally, old Austrian, French, and British newspapers in the library show that Yusuf Diya regularly read the overseas press. There is evidence that he received these materials via the Austrian post office in Istanbul, which was not subject to the draconian Ottoman laws of censorship.

As a result of his wide reading, as well as his time in Vienna and other European countries, and from his encounters with Christian missionaries, Yusuf Diya was fully conscious of the pervasiveness of Western anti-Semitism. He had also gained impressive knowledge of the intellectual origins of Zionism, specifically its nature as a response to Christian Europes virulent anti-Semitism. He was undoubtedly familiar with Der Judenstaat by the Viennese journalist Theodor Herzl, published in 1896, and was aware of the first two Zionist congresses in Basel, Switzerland, in 1897 and 1898. (Indeed, it seems clear that Yusuf Diya knew of Herzl from his own time in Vienna.) He knew of the debates and the views of the different Zionist leaders and tendencies, including Herzls explicit call for a state for the Jews, with the sovereign right to control immigration. Moreover, as mayor of Jerusalem he had witnessed the friction with the local population prompted by the first years of proto-Zionist activity, starting with the arrival of the earliest European Jewish settlers in the late 1870s and early 1880s.

Herzl, the acknowledged leader of the growing movement he had founded, had paid his sole visit to Palestine in 1898, timing it to coincide with that of the German kaiser Wilhelm II. He had already begun to give thought to some of the issues involved in the colonization of Palestine, writing in his diary in 1895:

We must expropriate gently the private property on the estates assigned to us. We shall try to spirit the penniless population across the border by procuring employment for it in the transit countries, while denying it employment in our own country. The property owners will come over to our side. Both the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly.

Yusuf Diya would have been more aware than most of his compatriots in Palestine of the ambition of the nascent Zionist movement, as well as its strength, resources, and appeal. He knew perfectly well that there was no way to reconcile Zionisms claims on Palestine and its explicit aim of Jewish statehood and sovereignty there with the rights and well-being of the countrys indigenous inhabitants. It is for these reasons, presumably, that on March 1, 1899, Yusuf Diya sent a prescient seven-page letter to the French chief rabbi, Zadoc Kahn, with the intention that it be passed on to the founder of modern Zionism.

The letter began with an expression of Yusuf Diyas admiration for Herzl, whom he esteemed as a man, as a writer of talent, and as a true Jewish patriot, and of his respect for Judaism and for Jews, who he said were our cousins, referring to the Patriarch Abraham, revered as their common forefather by both Jews and Muslims. He understood the motivations for Zionism, just as he deplored the persecution to which Jews were subject in Europe. In light of this, he wrote, Zionism in principle was natural, beautiful and just, and, who could contest the rights of the Jews in Palestine? My God, historically it is your country!