Under Siege: P.L.O. Decisionmaking During the 1982 War

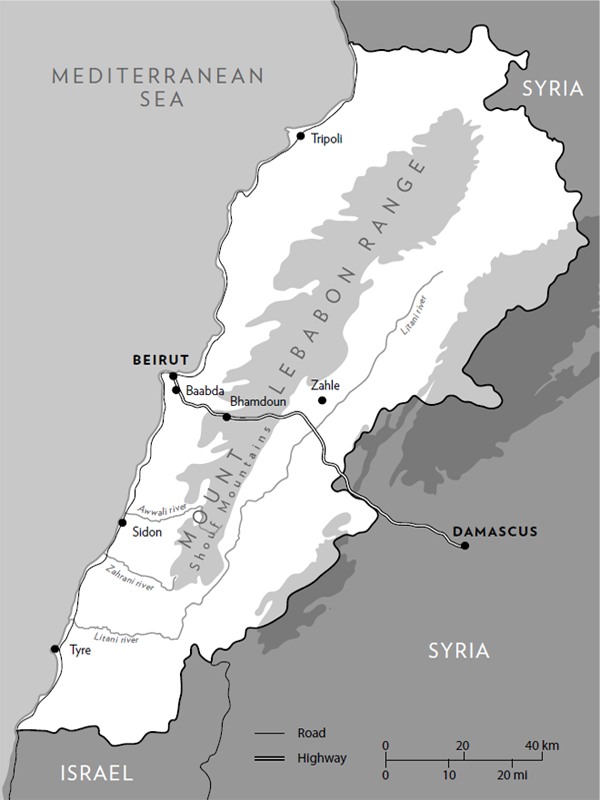

Lebanon

Under Siege: P.L.O. Decisionmaking During the 1982 War

Rashid Khalidi

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 1986 Columbia University Press

Preface to the 2014 Reissue 2014 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-53595-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Khalidi, Rashid.

Under siege : PLO decisionmaking during the 1982 war : with a new preface by the author / Rashid Khalidi.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-231-16669-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-231-53595-3 (e-book)

1. LebanonHistoryIsraeli intervention, 19821985.

2. Munazzamat al-Tahrir al-Filastiniyah. 3. Palestinian ArabsLebanonPolitics and government. I. Title.

DS87.53.K48 2014

956.052dc23

2013023427

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover design by Martin Hinze Cover image: The Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) firing position at Baabda near Beirut, Lebanon, during shelling of PLO positions, 1982. Micha Bar Am/Magnum photos

References to websites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or changed since the manuscript was prepared.

Contents

O ver thirty years have passed since the events described in this book, and more than a quarter of a century since it was first published in 1986. While a great deal has changed since then, much remains unchanged. At the same time, many of the crucial components and lessons of the Lebanese conflictincluding the Israeli-Palestinian war, which for nearly fifteen years was fought primarily on Lebanese soilseem to have been completely forgotten.

As I write these words in mid-2013, Lebanon is mercifully no longer subjected to a brutal, many-sided sectarian and proxy war. It is also no longer suffering from foreign military occupation, as it had been in 1982 and for many years thereafter. Unfortunately, the countrys fragile stability and its complex inter-sectarian balance are today being sorely tested by neighboring Syrias descent into a hellish civil warone that in some ways mirrors Lebanons own previous experiences.

Lebanons years of conflict, lasting from 1975 to 1990, offer many unlearned insights about the evils of sectarianism that Syrian and international actors should have taken into account in Syria over these past two years, but did not. Similar lessons were also ignored from 2003 onwards in Iraq by the American occupiers and many Iraqis. As the American occupation authorities and their Iraqi protgs re-engineered Iraqs political system to their advantage, they willingly adopted many of the worst aspects of Lebanons political sectarianism. What was thus established in Iraq was a deeply flawed confessional model that is essentially based on the divide and rule practices of the worst era of French colonialism, a system which contributed significantly to igniting three terrible sectarian civil wars in Lebanon between 1860 and 1975. This model has deepened and exacerbated existing societal fissures between different Iraqi religious sects and ethnicities: Sunnis, Shiites, Christians, Arabs, Kurds, Turcomans, and others. Of course, this imposed model did not birth a new, unified, federal, and democratic Iraq from the rubble of decades of Bathist tyranny, sanguinary warfare with Iran, and devastating American wars and sanctions. It instead helped generate massacres along religious lines, ethnic cleansing, the flight of millions of people from their homes, and the de facto partition of the country. Syria is currently prey to similar agonies.

Failure to avoid the pitfalls of sectarian, religious, and ethnic conflictcombined with external interventioncaused Lebanon to implode, followed by Iraq and now Syria. Significant elements of these three societies have been systematically pulverized in an analogous fashion. In all these cases, the destruction has overwhelmed and annihilated much of the painstakingly constructed modern infrastructure of government (some of it dating back to the Tanzimt reforms of the late Ottoman era); multiple layers of civil society as well as intellectual and cultural life; and vast areas of the economy, all while impoverishing and displacing large sectors of the population. The devastation of these three societies was the cumulative consequence of generations of poor governance and failed national leadership, the breakdown of unifying national narratives, and persistent and aggressive interference by foreign powers. All of these factors have produced savage civil wars in each country. Only many years after its own fifteen-year ordeal ended in 1990 was Lebanon able to regain a degree of internal equilibrium, however precarious.

In 2000, Israel ended its occupation of large parts of southern Lebanon. This occupation, which had begun on a smaller scale with the military incursion in 1978, reached its apogee and widest extent during the 1982 Israeli invasion, which is the backdrop to this book. The events of May 2000 marked the first and only time that Israel has ever withdrawn its military forces from occupied territory without any Arab or international quid pro quo. This tally includes Israels 2005 military redeployment from the Gaza Strip, since it did not fully end its occupation of, or cede its control over, that small region. Influenced by the wars outcome and even more so by Hizballahs victory in driving Israeli troops out of southern Lebanon, many of these Palestinian observers subsequently gravitated to armed radical groups like Islamic Jihad and Hamas, which had not even been established in the mid-1980s when this book was written. These groups have now become a powerful, even dominating, force in Palestinian politics. Unlike Hizballah in southern Lebanon, however, they have not yet proven themselves capable of parlaying armed resistance into completely ending Israeli occupation and control over any part of the territories occupied since 1967. Whether their military capabilities have even succeeded in deterring Israeli military action, or indeed whether they provoke its intensification, is a matter of a sharp and continuing Palestinian internal debate.

But for many other Palestinians, the 1982 war demonstrated the futility of the idea of armed resistance. Such individuals turned even more resolutely than before to a path of compromise and negotiations, producing a series of agreements with Israel that culminated with the so-called Oslo Accords. To the surprise of some, these accords, which were ostensibly meant to lead to peace and an end to the occupation, resulted in a re-invigorated and strengthened Israeli occupation regime. In the shadow of these agreements, and in some measure because of them, the Jewish settler population in the West Bank and Arab East Jerusalem has nearly tripledfrom about 200,000 at the time of the Madrid peace conference in 1991 to almost 600,000 presently.

The Oslo Accords and the intensified regime of Israeli occupation and settlement that has emerged from them are now seen by most Palestinians as highly inimical to their national interests and aspirations. Nevertheless, many others still cling to the Palestinian Authority that is the centerpiece of this post-Oslo regime, for reasons ranging from the opportunistic to the idealistic. But the perceived failure of the negotiating route adopted by the PLO since the 1980s (with its roots in crucial Palestinian decisions of the early and mid-1970s to favor a path of negotiations) has inevitably strengthened the alternatives. These alternatives range from popular mass nonviolent resistance to the Israeli military occupation; through protests and efforts to use boycotts, divestments, and sanctions against Israel; to armed resistance to Israels unremitting control over Palestinian territories and populations. From this, we can see that Palestinians learned a plethora of different lessons from the 1982 war and its aftermath in Lebanon.