The world is undergoing an energy transition with enormous implications for housing and architecture. This essay will briefly examine the shift to a new energy regime and locate that change in an historical overview of previous energy systems in the United States. After providing this framework, it will consider different explanations for the energy inefficiency in US housing and compare the current situation with the previous energy transition of the 1920s, when a majority of American housing was electrified in less than a generation.

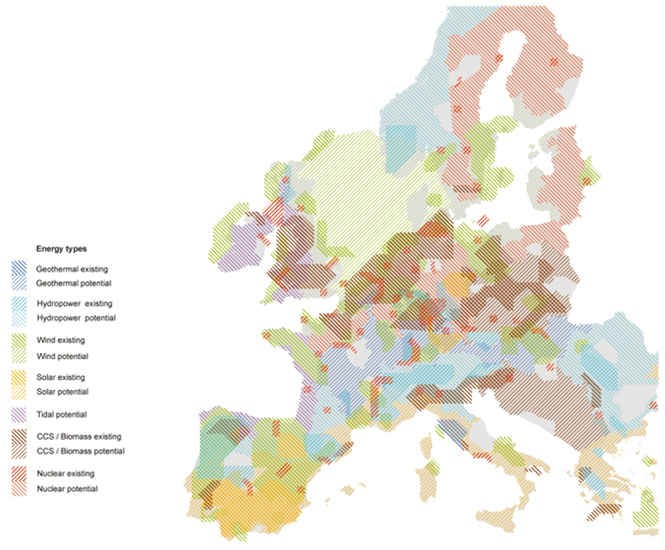

If history is any guide, the shift to alternative energy production and to high-intensity energy consumption will require half a century. This process reached an important landmark when the International Energy Agency announced that emissions of carbon dioxide were the same in 2014 as in 2013, even though the world economy grew by 3.3% that year(International Energy Agency, 2014). This two-pronged changemore efficient energy consumption and more alternative energy productionhas been a trend for four decades in advanced industrial economies. Improved energy intensity meant that the 2008 American economy used only half as much energy to produce one dollar of GDP as it had in 1970 (Sovacool, 2008, 8081). However, US economic growth more than offset this improvement. American CO2 emissions leveled off because of changes in production, notably a switch from coal to natural gas and to alternative energies. In terms of housing, the shift to a new energy regime has been slower than in Europe.

Previous Energy Regimes and Transitions

During the nineteenth century the United States was a leader in the adoption of new energy forms. In each case, the transition required forty to fifty years (Nye, 1998, passim). It required fifty years (1790-1840) to build a system of water-powered factories that were the basis for industrialization. Steam power was rare before ca. 1820, and required half a century to achieve dominance in 1870. The shift to electrification took until 1930, while the transition from coals dominance to oil and natural gas lasted from ca. 1910 to 1960. One may debate precise dates for these transitions, but none was accomplished in less than four to five decades. Former Vice President Al Gore has called for a new transition in just one decade, but implementing a new energy regime is difficult to accomplish quickly. It is a complex social process involving many actors, not all of whom will gain from the transaction. For homeowners, a new or renovated house with excellent insulation and low energy demand is a large investment. Electrification of American homes did not entail a decline in the use of coal, gas, or oil. But in the new energy transition overall consumption will need to decline, which is historically unusual, as Jevonss paradox comes into play (see David Owens essay on this issue). Moreover, utilities are at best ambivalent about reductions in consumer demand. Power plants are expensive and built to remain operational for decades. Closing them is only economically attractive after utilities amortize the cost of construction, and therefore utilities have developed alternative energies more often as additional capacity for growing markets than as substitutes for existing power systems to be taken off line.

The United States was the worlds leader in electrification. Americans electrified their homes sooner and made more extensive use of appliances than Germany, Britain, France, or Japan. However, high US energy use became so embedded in the landscape that it is difficult to shift to alternative energies. Americans society is deeply intertwined with single-family suburban homes and an energy-demanding form of life. It is therefore useful to examine the transition when Americans electrified their homes and established the foundations for their high-energy lifeworld.

The Situation In 2015

After American houses were electrified in the cities and suburbs during the 1920s and in rural areas during the 1930s, domestic energy use skyrocketed. Between 1940 and 2001 the average household increased electrical consumption 1300%. A typical family in 2015 used more electricity each month than their grandparents had consumed in a year (Fahrenthold, 2010). Since 1940, the average family has acquired televisions, dishwashers, microwaves, clothes dryers, freezers, stereos, power tools, answering machines, DVDs, air conditioning, computers and printers, heated water beds, outdoor electric grills, and hot tubs, to make a short list (Nye, 2010, 142). Additional appliances offset improved efficiency for individual devices. (US Census 2011) The refrigerator or the washing machine may use only half as much energy as it once did, but on a per-capita basis, Americans still require about 70 million British thermal units a year to heat, cool and power their homes, just as they did in 1971 (Fahrenthold, 2010). Furthermore, because the US population has increased from 203 million in 1970 to more than 310 million in 2015 there has been a corresponding 50% increase in energy demand. The World Bank reports that in 2012 the US consumed per capita the equivalent of 6,794 kg of oil, compared to 3,832 in France, 3,822 in Germany, 3,539 in Japan, and 3,020 in Great Britain (World Bank, 2015). With the same per capita energy use, Germanys economy was far stronger than that in France, and it would seem hard to claim that using twice as much energy as Japan made the US economy twice as efficient or twice as successful. The average American home wastes heat, pollutes the air, accelerates global warming, and drains the family income.