A volcano has been extinguished.

But the glow of the lava which poured out so copiously and brilliantly from it... would long remain in the memories of men and annals of history.

A First Word

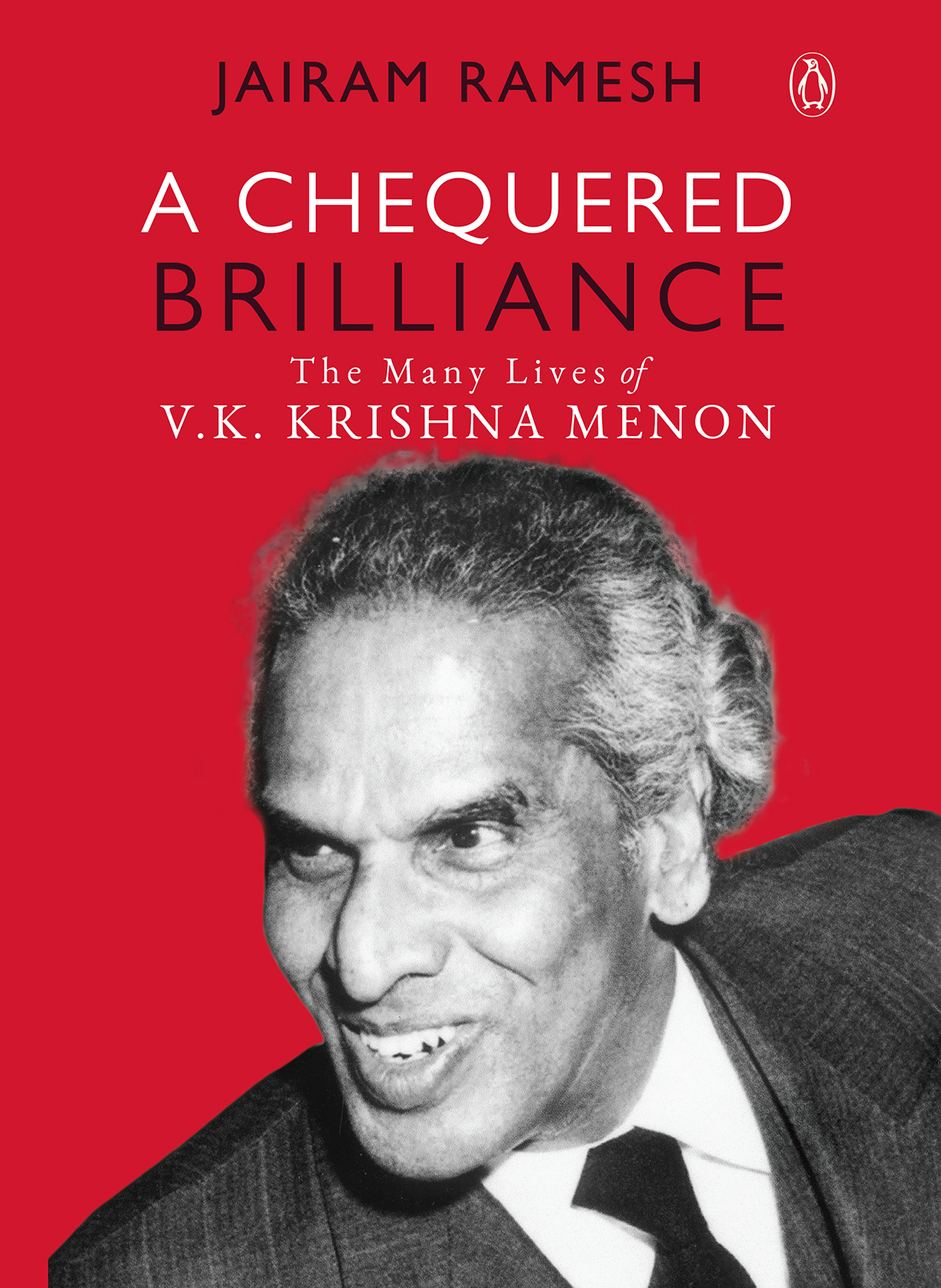

T his is a book on one of Indias most compelling, consequential and controversial political personalities. He has been referred to at various times as Rasputin, Mephistopheles, Lucifer, Svengali, Evil Genius, The Worlds Most Hated Diplomat, Sombre Porcupine, The Formula Man and other colourful images. He was both admired and admonished for over three decades.

He was first discovered in Madras sometime in 1916 or 1917 by the extraordinary Irishwoman Annie Besant, who had made India her home, but it was his avatar as Jawaharlal Nehrus soulmate, sounding board and envoy between 1935 and 1964 that earned him a permanent place in Indias twentieth-century history.

He spent twenty-three years in London agitating and making the case for Indias freedom with political parties and parliamentarians, trade unions, universities, the media, literary and cultural personalities and all sorts of civic organizations across the UK. In that period he was also the editor of a number of well-known books published in the mid-1930s and helped establish the highly regarded publishing imprint Pelican Books.

He had a key role to play in making the Korean armistice possible in 1953 and in contributing to a political settlement on Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos in 1954. He was very active in defusing tensions between the US and China in 1955.

He figured constructively in the negotiations to end the Suez Canal crisis in 1956 but drew criticism for his stance on the Soviet invasion of Hungary that took place almost at the same time.

He holds the record for having made the longest speech at the United Nations (UN) in 1957, running into some eight hours spread over two days and defending Indias case on Kashmir. The speech was not only exhaustive but was evidently so exhausting that he collapsed soon after making it and required medical attention in order to resume.

He finds significant mention in histories of the negotiations over nuclear disarmament, the struggle against colonial rule in Africa, the emergence of Cyprus, the campaign against apartheid in South Africa and the crisis in Congo. Out of power and in the political wilderness between 1963 and 1974, he became a crusader for world peace and the abolition of war.

He was seen as the architect of Indias liberation of Goa from Portuguese rule in 1961, which earned plaudits at home but drew intense criticism in the West. He continues to be held chiefly responsible for Indias military debacle in the war with China a year later. He was forced to resign as Indias defence minister in November 1962 but grew in stature subsequently. His reputation was redeemed to a large extent by the dignified manner in which he handled his ejection from the pinnacle of power.

He spent three decades crusading against the British rule in India, but after the transfer of power was accomplished, he strongly advocated India remaining in the Commonwealth. He was a municipal councillor for a long time in London and almost became an MP in the UK House of Commons. Upon his death, seven of his British friends, all distinguished men and women in their own right, issued a statement calling him a good Britisher and a true Indian.

His two elections as a Lok Sabha MP from North Bombay in 1957 and 1962 made global headlines and his campaigns drew film stars, literary figures and eminent professionals. Denied a ticket in 1967, he quit the Congress after a three decade-long association and returned to Parliament in 1969 and 1971 as an independent supported by the communist and other left parties.

He had an uncanny ability to make instant enemiesand there were many of them. Even so, he had a legion of acolytes and admirers. He evoked strong criticism for his style even as he was grudgingly applauded for his substance. He hobnobbed with presidents and prime ministers of different countries, many of whom found him brilliant but exasperating.

Many years after his death, buildings and roads were named after him and statues erected in India. In 2008, the South African government recognized his contributions to the ending of apartheid, and five years later, the Bangladesh government honoured him for his role in the emergence of that country. A plaque marking the place where he stayed and a bust of him as well can be found in London.

This man is V.K. Krishna Menon, at once both cantankerous and charming, a man well-endowed with both eccentricities and capabilities that make him a continuing field of excavation.

In the Nehruvian era, there was an age of V.K. Krishna Menon. This book recalls that age.

* * *

Over the past quarter of a century, substantial new material in which Krishna Menon figures prominently has become available in archives in different countries, including India, the US, the UK, Canada, Sweden, Russia, France, China and Australia. Krishna Menons own papers, humungous as they are, were made available to the public only in early 2019. Till the mid-1990s, just thirty-one volumes of the Selected Works of Jawaharlal Nehru had been published and those too had not been excavated meaningfully. Since then another sixty-five volumes have appeared. A careful reading of them is required to understand the evolution of twentieth-century India. They provide a window into the mind of the architect of the modern Indian nation-state. For a quarter of a century beginning 1935, the largest part of Nehrus correspondence, barring that with his daughter, was with Krishna Menon, in which the two shared their innermost thoughts on important issues and the personalities of the day and bared their souls to each other.