INFINITE VARIETY

There are so many ways of doing everything, all over India,

that descriptions quickly fade into falsehood.

E.M. Forster, Abinger Harvest (1935)

If not him, there is his brother

Mir, are there any restrictions in love?

Mir Taqi Mir (1723-1810)

Like a silkworm weaving

her house with love from her marrow,

and dying in her bodys threads winding tight,

round and round,

I burn desiring what the heart desires.

Mahadeviyakka (12th century CE)

Passion knows no order.

Vatsyayana, Kamasutra (3rd century CE)

Contents

INTRODUCTION

A History of Impurity

Two women sip wine as they caress one another. All around them is beauty and light. They enjoy the revels with abandon, their jewels sparkling, and look straight at the artist who is putting up their image for posterity. People from around the world will see this image and wonder at its sensuality.

An Instagram photo taken in one of the metropolises of the world in the 21st century, you think? No. Try an 18th-century painting from rural Rajasthan.

I first went to the village of Samode in 2014. We set off from Delhi at the crack of dawn, to escape the heavy traffic that builds up after daybreak around the industrial hub of Manesar. It was a hot day in August, and the sun was bright even at 6.30 in the morning. After a five-hour drive, we arrived at a grand hotel in Rajasthan, 40 kilometres north of the state capital Jaipur. Built as a fort in the 16th century and then converted into a palace in the early 19th century, Samode Palace is now a heritage hotel. It has a magnificent Sheesh Mahal, or Palace of Mirrors, and its Darbar Hall is decorated from floor to ceiling with exquisite paintings. The palace is built in the syncretic Muslim-Hindu style of architecture, and the paintings all use vivid pigments. The artwork draws from themes both religious and secularsensuous images of Krishna and Radha vie for space with our two women, who in turn rub shoulders with soldiers and sadhus. Desire is of the world, and it extends across what we now term hetero- and homo-sexuality, both of which co-exist happily alongside polyamory (Krishna with many gopis) and celibacy (saints with matted hair).

I am fascinated by these multiple versions of desire because these are the desires with which I grew up. All around me in the Delhi of the 1970s and 80s were Hindi films that celebrated same-sex attachments (Anand), older women desiring younger men (Doosra Aadmi), and cross-couple desire (Angoor). Equally, there was Bharatanatyam dance in which dancers played the parts of both men and women, lover and beloved. Sufi qawwalis that sang of mutual longing between two men. And dotting the landscape were transgendered hijras whom we were taught to respect at all times.

In the West, these multiple desires are greeted as new-fangled ideas, and in India now they are increasingly treated as foreign conspiracies. It was only after returning from 18 years of studying and working in the US that I was able to realize the complexity of this landscape of desire.

The legendary actor and singer Bal Gandharva,

who performed female roles in several

popular Marathi plays in the early 1900s.

Source: YouTube

When I first decided to move back to Delhi, friends and colleagues asked me how I would continue my work on queer theory in a country that was becoming increasingly puritanical and sexually violent. The pub attacks in Bangalore on Valentines Day had already happened, reports of rape were on the rise, and misogyny was getting nationalized. Homosexuality had always been outlawed under an outmoded British law and was soon to be recriminalized after a brief reprieve.

But: despite a scant academic presence of sexuality studies in the form of syllabi, centres and university departments, India has a lived relation to desire that makes it much easier to speak about various desires to a wider audience. Millions of people know the stories of cross-dressing gods. Men hold hands freely. Women frequently sleep in the same bed. This is a country that is deeply homophilic even as it is often superficially homophobic. The intellectual and cultural histories of desire are both broad and deep: here, desire is not just, or even primarily, an academic subject. I soon realized that my interest in desiremy desire for desirewas not a consequence of my graduate work in the US. Rather, my graduate work on desire was a consequence of the fact that I had grown up in India.

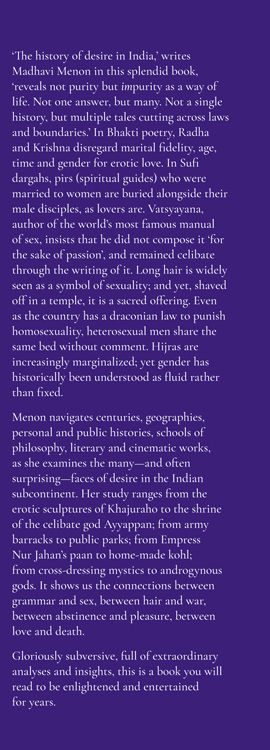

Because desire here is everywhere. I daresay that is true all over the world, but both the restrictions and the permissions seem to be more intense here. What is considered taboo in the USheterosexual men sharing the same bed, for instancepasses here without comment. And what elicits no reaction in other placesthe length of ones hair, for exampleis intensely policed and debated here. In India, even a law against homosexuality does not prevent a simultaneous law supporting transsexuality. Consistency is not the favoured mode in India, especially in relation to desire. We have very strict rules about What Must be Done: (heterosexual) marriage and producing children are flourishing businesses. But equally, we have long histories that valorize celibacy, and goddesses who model childlessness. So which one is the real India? The answerfortunately for usis all of the above. The history of desire in India reveals not purity but impurity as a way of life. Not one answer, but many. Not a single history, but multiple tales cutting across laws and boundaries.

What I find fascinating is how much this impurity offers a counterpoint to regimes of desire in other parts of the world. For example, sexual repression in India has historically been foisted on hetero- rather than homo-sexuality. As a gay man from Bangalore told the mathematician Shakuntala Devi in a 1976 interview she recorded in The World of Homosexuals:

Some heterosexuals are much more oppressed. I couldnt have lived with Seenu for nearly four years so openly had he been a woman. I darent be seen with a girl so often in public as I do with Mohan. Somehow people are so little aware of homosexuality in this country, though such a lot exists. Two boys, or for that matter two girls, can do anything they want, no one says anything. Not even parents suspect. But a boy and a girl cant get away with it.

One way of explaining the acceptability of this public camaraderie is that people here do not always recognize same-sex intimacy as being sexual. Heterosexuality is closely monitored in India because that is where people assume sex takes place. Unmarried men and women cannot mingle freely without inviting disapproval. But men together and women together in close and even intimate proximity do not elicit a second glance. They tend to fly below the marriage radar, and so their sexual activity or inactivity is not presumed. Equally, however, one might think of this laissez faire attitude towards same-sex intimacy as a historical reminder of what was once commonplace and continues to thrive in popular activities such as the launda naach, in which men dress as women and perform satirical plays and provocative dances.

A related reason for this seeming nonchalance towards same-sex intimacy is that sexualities have not always been

Next page