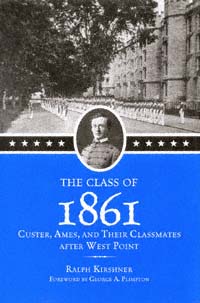

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "The Class of 1861: Custer, Ames, and their classmates after West Point, Volume 1861" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

George Armstrong Custer wrote about his friend Pierce Manning Butler Young, who left West Point to become a Confederate general: I remember a conversation held at the table at which I sat during the winter of 6061. I was seated next to Cadet P. M. B. Young, a gallant young fellow, a classmate of mine, then and since the war an intimate and valued frienda major-general in the Confederate forces during the war and a member of Congress from his native State [Georgia] at a later date. The approaching war was as usual the subject of conversation in which all participated, and in the freest and most friendly manner. . . . Finally, in a half jocular, half earnest manner, Young turned to me and delivered himself as follows: Custer, my boy, were going to have war. Its no use talking: I see it coming. All the Crittenden compromises that can be patched up wont avert it. Now let me prophesy what will happen to you and me. You will go home, and your abolition Governor will probably make you colonel of a cavalry regiment. I will go down to Georgia, and ask Governor Brown to give me a cavalry regiment. And who knows but we may move against each other during the war. . . . Lightly as we both regarded this boyish prediction, it was destined to be fulfilled in a remarkable degree. Ralph Kirshner has provided a richly illustrated forum to enable the West Point class of 1861 to write its own autobiography. Through letters, journals, and published accounts, George Armstrong Custer, Adelbert Ames, and their classmates tell in their own words of their Civil War battles and of their varied careers after the war. Two classes graduated from West Point in 1861 because of Lincolns need of lieutenants, forty-five cadets in Amess class in May and thirty-four in Custers class in June. The cadets range from Henry Algernon du Pont, first in the class of May, whose ancestral home is now Winterthur Garden, to Custer, last in the class of June. Only thirty-four graduated, remarked Custer, and of these thirty-three graduated above me. West Points mathematics professor and librarian Oliver Otis Howard, after whom Howard University is named, is also portrayed. Other famous names from the class of 1861 are John Pelham, Emory Upton, Thomas L. Rosser, John Herbert Kelly (the youngest general in the Confederacy when appointed), Patrick ORorke (head of the class of June), Alonzo Cushing, Peter Hains, Edmund Kirby, John Adair (the only deserter in the class), and Judson Kilpatrick (great-grandfather of Gloria Vanderbilt). They describe West Point before the Civil War, the war years, including the Vicksburg campaign and the battle of Gettysburg, the courage and character of classmates, and the ending of the war. Kirshner also highlights postwar lives, including Custer at Little Bighorn; Custers rebel friend Rosser; John Whitney Barlow, who explored Yellowstone; du Pont, senator and author; Kilpatrick, playwright and diplomat; Orville E. Babcock, Grants secretary until his indictment in the Whiskey Ring; Pierce M. B. Young, a Confederate general who became a diplomat; Hains, the only member of the class to serve on active duty in World War I; and Upton, the class genius. The book features eighty-three photographs of all but one of the graduates and some of the nongraduates. Kirshner includes an appendix entitled Roll Call, which discusses their contributions and lists them according to rank in the class. George A. Plimpton provides a foreword about his great-grandfather, Adelbert Ames-Reconstruction governor of Mississippi and the last surviving Civil War general-and President Kennedy.