Copyright 2019 by The University of Arkansas Press

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-68226-099-9

eISBN: 978-1-61075-669-3

23 22 21 20 19 5 4 3 2 1

Designed by Liz Lester

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bolton, S. Charles, author.

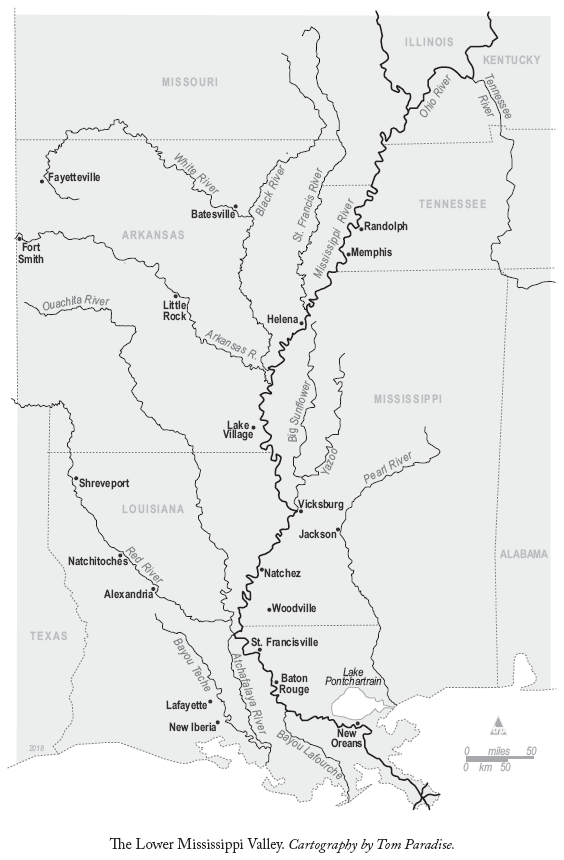

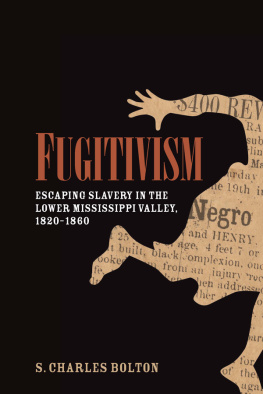

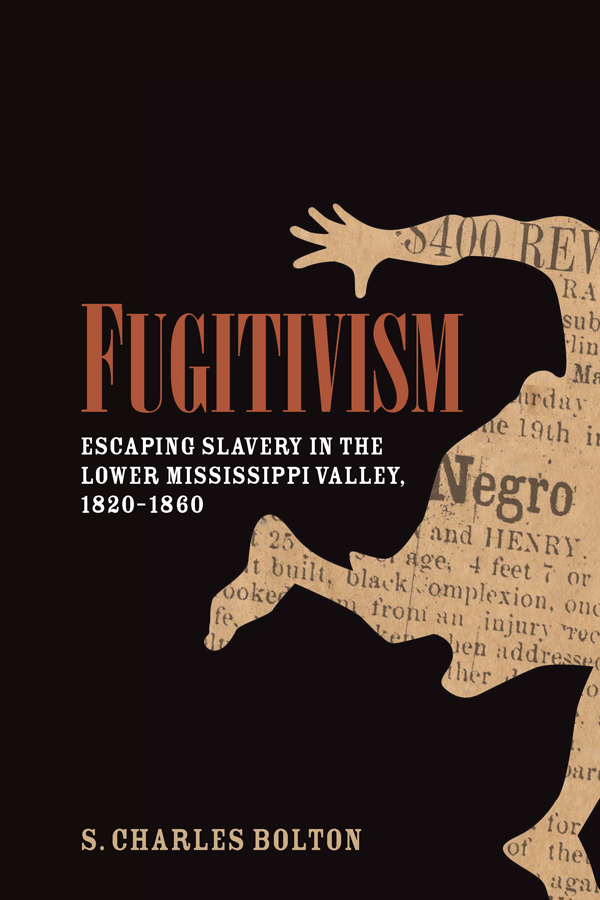

Title: Fugitivism : escaping slavery in the lower Mississippi Valley, 1820-1860 / S. Charles Bolton.

Description: Fayetteville, AR : The University of Arkansas Press, [2019] | Series: Arkansas history | Includes bibliographical references and index. | Identifiers: LCCN 2018054035 (print) | LCCN 2018056149 (ebook) | ISBN 9781610756693 (electronic) | ISBN 9781682260999 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Fugitive slavesMississippi River Valley RegionHistory19th century. | SlaveryMississippi River Valley RegionHistory19th century. | SlavesSouthern StatesSocial conditions.

Classification: LCC E450 (ebook) | LCC E450 .B69 2019 (print) | DDC 306.3/620977dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018054035

Supported by the Gordon Morgan Publication Fund

For Lillie, Ilan, Casimir, Zara, Mari, and Archer

I bathed in the Euphrates when dawns were young,

I built a hut near the Congo, and it lulled me to sleep,

I looked upon the Nile and raised pyramids above it.

I heard the singing of the Mississippi when,

Abe Lincoln went down to New Orleans,

And Ive seen its muddy bosom turn all golden in the sunset.

LANGSTON HUGHES, The Negro Speaks of Rivers,

The New Negro: Voices of the Harlem Renaissance,

Edited by Alain Locke, Introduction by Alan

Rampersad (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), 141.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I began to think seriously about runaway slaves in 2006 when James Hill of the National Park Service (NPS), National Underground Railroad Network to Freedom, and Susan Ferentinos of the Organization of American Historians contacted me about a project that the NPS later published as Fugitives from Injustice: Freedom Seeking Slaves in Arkansas, 18001869. A keynote address to the Arkansas Historical Society in 2008 provided an opportunity to discuss my idea about expanding that project to the Lower Mississippi Valley.

I am grateful to Morris S. Arnold for helping me understand colonial Louisiana and reading a penultimate version of , and Vince Vinikas for reading and editing three chapters. Conevery Valenius read the entire manuscript and offered perceptive suggestions, some of which I ignored until they were reinforced by an anonymous publication referee. Brian Mitchell shared his knowledge of New Orleans at the early stages of the project, and Rod Lorenzen helped me improve the manuscript at the end.

Ottenheimer Library of the University of Arkansas at Little Rock assisted me in many ways. I am also grateful to the staffs of the Benjamin L. Hooks Central Library in Memphis, the Butler Center for Arkansas Studies at the Central Arkansas Library, the UALR Center for Arkansas History and Culture, the Special Collections Room at the Hill Memorial Library at LSU, the Louisiana Collection at Tulane University, and the Historical Archives of the Louisiana Supreme Court at the University of New Orleans. Amanda Paige, a historian in her own right, provided much valuable assistance on this book.

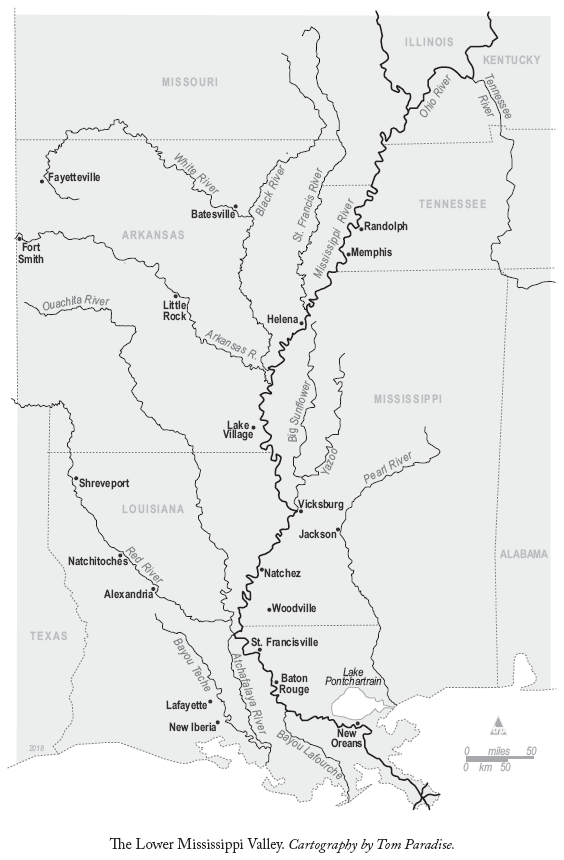

Many thanks to the people at the University of Arkansas Press and to Tom Paradise, cartographer extraordinaire.

On a personal level, I want to thank the parents of the people to whom this book is dedicated: Shannan Venable, Conevery and MattValenius, and Jesse Bolton and Angie Anderson. Bettina Brownstein encouraged my efforts on this project from beginning to end and served as a role model for the concept that retirement is a good time to do for satisfaction the useful work you used to do for money. I am also grateful for the support of my friends of many decades Gene and Diane Lyons, Judy and Davis Bullwinkle, Jeanne Joblin, and Carla Anderson. Small but very enjoyable portions of the work were done in Ada Halls kitchen with its wonderful view of Lake Winnebago. The multifarious activities of the Endorfemmes and their menfolk and associates, and the regular meetings of Earl Ramseys floating poker game, provided a conviviality for which I am grateful.

INTRODUCTION

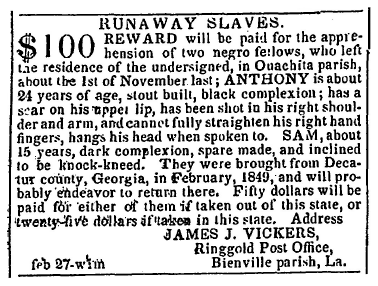

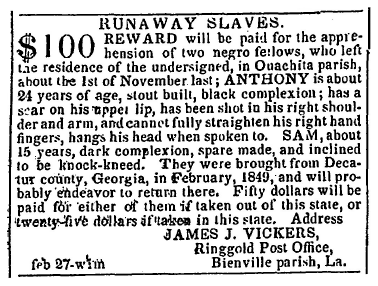

On page three of the March 6, 1850, edition of Natchezs Mississippi Free Trader and Gazette, nestled among the advertisements was the following notice:

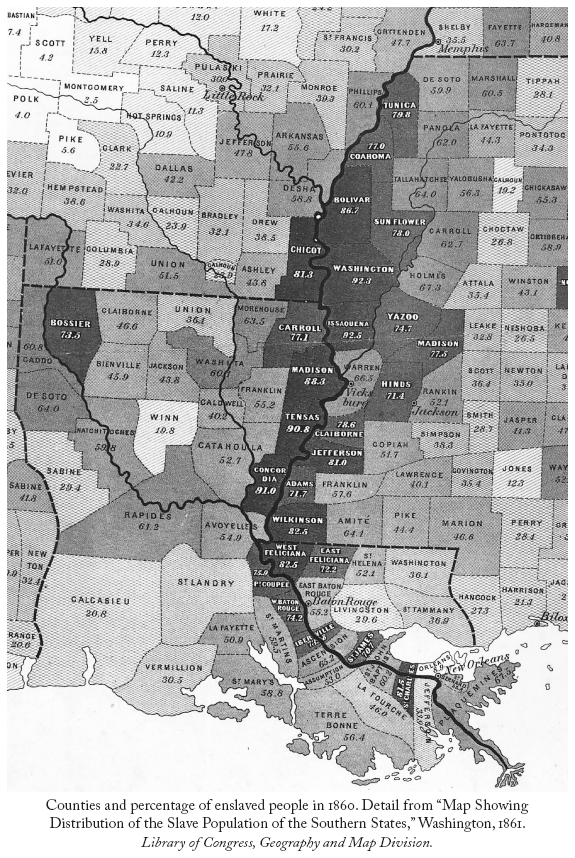

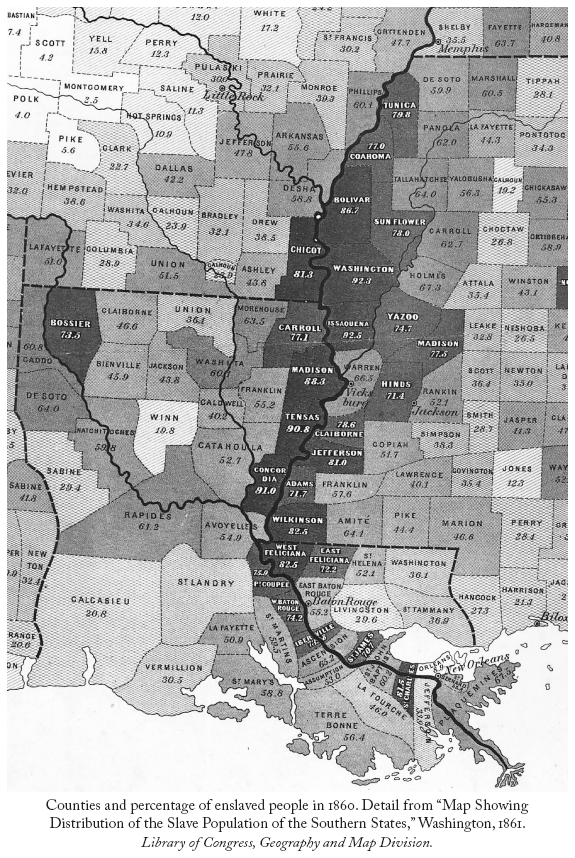

Advertisements such as this one had been common in southern newspapers for more than a century, and they are very good sources of information. Owners included all the details they thought would help in finding their property, and while some of their comments reflect racial stereotyping, we may assume that other details were as accurate as the subscribers could make them. Based on an analysis of many ads, we know nine out of ten of those being sought in most parts of the Lower Mississippi Valley were males like Anthony and Sam. At age fifteen, Sam was a little younger than most of them, who ranged in age from the late teens to the middle thirties. Anthonys black complexion suggests his African ancestry and Sams dark skin probably also, but more than a third of the runaways were mixed-race people usually described in various shades of yellow or copper. In New Orleans the word mulatto described a person who was half black, and griffe, one that was one quarter black. Anthonys downcast look when addressed by white peoplewas probably less a personality trait than a conscious attempt to project a false image of submissiveness that was belied by the rebellious act that got him into the papers. Physical descriptions that included gunshot wounds like Anthonys were rare, but about 3 percent of advertised runaways bore permanent marks of punishment. If James Vickers, their owner, was correct, and he probably was, Anthony and Sam were also typical fugitives in that they were heading for someplace in the South rather than to a free state in the North, motivated by the desire to be with friends, lovers, or family or to enjoy the excitement of a city and the fellowship of the black communities to be found there.

Running away from slavery was common enough to become a metaphor for many other kinds of escapes. There were runaway horses, runaway brides, runaway debtors, and the ceremony that followed elopement was sometimes referred to as runaway marriage. A Mississippi woman named Fanny Budlong ran an ad in an Alexandria, Virginia, paper looking for her husband whom she called not only a runaway but also a drunkard and a Jackson man. The verbal ran away was commonly shortened to one word, as in the phrase he ranaway.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials Z39.48-1984.