Design and composition: Jennifer Cropp Printing and binding: Integrated Book Technology, Inc.

Typefaces: Minion and Bernhard

For Gloria Ekberg and in memory of Ida Nasatir, two wives who endured much on behalf of Upper Louisiana

Foreword

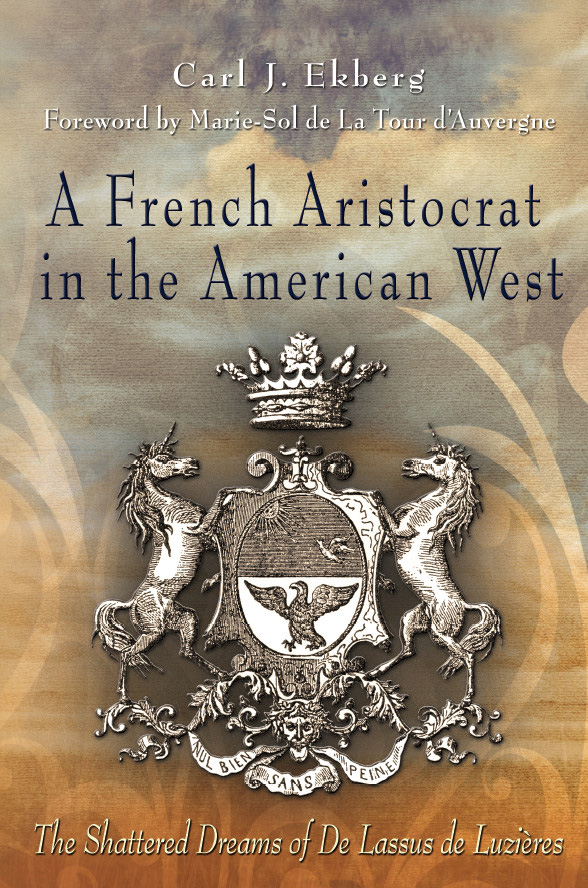

Pierre-Charles de Hault de Lassus de Luzires was one of a number of French aristocrats who sought their fortune in America during the turbulent times ushered in by the French Revolution. This seismic political and social upheaval reverberated across both Europe and America. Far more French aristocrats invested in land in America than actually settled there. De Luziress case is exceptional, both because he settled permanently in the Mississippi Valley and because the story is so remarkably well documented. Carl J. Ekberg has skillfully brought to life the frontier struggle of this transplanted Frenchman who courageously adapted to challenging circumstances at a time in life when most men of his age and standing aspired to a genteel retirement on their estates.

De Luziress arduous journey, which involved uprooting his family in northern France and setting sail for America in 1790 for what he thought would be a 2,000-acre tract on fertile lands on the banks of the Ohio River, proved to be just the beginning of his adventures. He soon discovered that he had been defrauded by the infamous Scioto Land Company. With that dream in ruin, he set about realizing anothercreating a vast commercial empire in the Illinois Country, which would extend the entire length of the Ohio River and down the Mississippi from Ste. Genevieve to New Orleans. By this time well in his fifties, he eventually made a name for himself in Nouvelle Bourbon, which he named after the French royal family. This was only fitting because he remained a committed monarchist for his entire life. Although many of de Luziress vast ambitions were not realized, he showed a remarkable persistence in bringing settlers to New Bourbon, which remained a Francophone bastion in Spanish-ruled Louisiana.

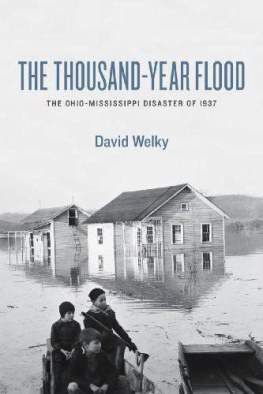

I first came in contact with the region, which witnessed such an influx of my countrymen two centuries earlier, while flying over the flooded Mississippi Valley in 1993. This devastating flood threatened to wipe out every trace of the French presence, dating from the eighteenth century, in that part of the United States. This was the first time I discovered the French presence in the Mississippi Valley, and it made a profound impression on me. As the consul gnral of France from Chicago and I flew over the flooded Mississippi Valley, I discovered the French settlements at Ste. Genevieve and Kaskaskia (with its remarkable bell, a gift from France). With the immense devastation before my eyes, I realized how impetuous and dangerous this river could be. I thought of the loss of land that the inhabitants suffered in the face of this mighty force of nature. I also imagined the difficulties the early French colonists faced in settling this area of vast and imposing wilderness.

Once we landed and visited the communities, I immediately fell in love with the vernacular vertical-log houses with their French influences and their graceful galleries. The houses displayed a unique character having taken on local attributes of the areabut on the inside they were exactly like French country houses, especially the fine Louis Bolduc House restored thanks to the Colonial Dames of the State of Missouri. It was also fascinating to discover the ancient agricultural pattern, which had been transported from France, with its narrow, long fields laid out facing the river, where the habitants practiced communal farming. I was briefly transported across time and distance with these evocations of France delineated in the earth right in the heart of America.

Culturally, I felt a poignant emotional jolt, a profoundly moving shock of recognition, when I heard a childrens choir from Ste. Genevieve sing, in French, very ancient Christmas songs that we sang at midnight mass during my childhood in my small village in the Berry region of central France. That touching testimony to the French presence as far back as the seventeenth century reinforced the notion of that shared cultural link, which is today slowly eroding even in our French country villages. That it remained alive in this small Mississippi Valley town was deeply moving. I discovered that many folks in the region were extremely proud of their French origins.

After the great flood, we at the French Heritage Society helped to preserve Ste. Genevieve by awarding a number of restoration grants over the years, but it remains a heritage in peril. Some vertical-log structures, like the Bequette-Ribault House, are in very fragile condition, while others have been much modified by successive waves of owners who lived in them, whether they were English, German, or American. Nevertheless, it is an invaluable and unique heritage, for these houses and villages are a rare testimony of the French presence in America during the colonial period.

The majestic Mississippi River was called the Colbert in the seventeenth century, after Louis XIVs powerful minister, Jean-Baptiste Colbert. He promoted French colonization in America and firmly believed in the opportunities it offered for the economic development of France. He supported Robert Cavalier de la Salles expedition to the mouth of the Mississippi River in 1682 and urged Louis XIV to promote French settlement in the Mississippi Valley. Colbert is an ancestor of mine on my mothers side, and I am understandably proud of the role he played in the history of North America. We still have in our family chteau paintings, objets dart, books, and manuscripts that belonged to Colbert, including a wonderful portrait of him by the seventeenth-century-master Claude Lefbvre.

I am also proud of the major role played by young French aristocrats during the American War of Independence, who, leading their regiments, came to reinforce and train the American insurgents. Their passion spread to other French aristocrats, and following the example of Benjamin Franklin, inspired them to raise funds and fight for the ideal of a free people. The contributions of the Marquis de Lafayette and the Comte de Rochambeau are well known, but others from all corners of Franceher cities, villages, and countrysidealso sailed for America, bringing with them professional military knowledge, engineering expertise, and the fighting spirit of a traditional warrior class. One of these was the abb Paul de St. Pierre, formerly a chaplain in the French expeditionary force, who served as a much-beloved cur in Ste. Genevieve during the 1790s.

I have great hopes for the Illinois Country, which was settled by my countrymen so long ago, to serve as a focal point for interpreting French colonial settlement in North America. I left a part of my heart in Ste. Genevieve on the banks of the Mississippi, but I also left an uncompleted task, which is the proposed establishment of a French Heritage Park in the area. There is still so much to be done in Ste. Genevieve in order for this village to be restored to its eighteenth-century appearance when it flourished along the banks of the Mississippi, its fertile lands supplying the major French city in America, New Orleans, with foodstuffs. It is, for me, a passionate adventure, just as passionate as de Luziress during his day, though fraught with far less danger than he faced in navigating and settling the American frontier. But it is a challenge suited to our times. And I share with de Luzires that ideal to see the French heritage flourish along the banks of the Mississippi.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.

This paper meets the requirements of the American National Standard for Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, Z39.48, 1984.