About the Authors

Marjorie Agosn is an award-winning poet, activist, teacher, and the Luella LaMer Slaner Professor of Latin American studies at Wellesley College. She has won important literary and human rights prizes and has published memoirs, fiction, and poetry.

Isabel Allende is a teacher, playwright, and novelist. Winner of many prestigious awards, she treasures letters from her readers. Allendes most recent novel is Ins of My Soul (2006), called a swift, thrilling epic, packed with fierce battles and passionate romance by Publishers Weekly . Allende was born in Chile and sets much of her writing in that country. She is well known for her magical realism and vivid storytelling.

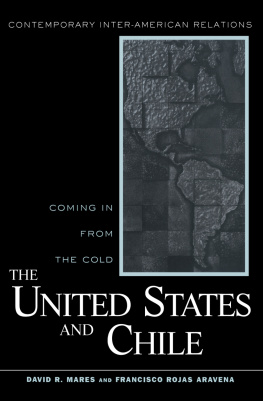

Peter Kornbluh is the director of the Chile Documentation Project at the National Security Archive, a public interest research center in Washington, D.C. He is the author of The Pinochet File: A Declassified Dossier on Atrocity and Accountability .

Peter Winn is professor of history and director of Latin American Studies at Tufts University. He is the author of Weavers of Revolution: The Yarur Workers and Chiles Road to Socialism (1986) and Americas: The Changing Face of Latin America and the Caribbean (3rd Ed., 2006) and the editor of Victims of the Chilean Miracle: Workers and Neoliberalism in the Pinochet Era, 19732002 (2004).

Tapestries of Hope, Threads of Love

ROWMAN & LITTLEFIELD PUBLISHERS, INC.

Published in the United States of America

by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

www.rowmanlittlefield.com

Estover Road, Plymouth PL6 7PY, United Kingdom

Copyright 2008 by Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

All rights reserved . No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Agosn, Marjorie.

Tapestries of hope, threads of love : the arpillera movement in Chile / Marjorie Agosn. 2nd ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-4002-6 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-7425-4002-2 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN-13: 978-0-7425-4003-3 (pbk. : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-7425-4003-0 (pbk. : alk. paper)

1. Women in politicsChileSantiago. 2. ChilePolitics and government 1973 3. Disappeared personsChileSantiago. I. Title.

HQ1236.5.C5A36 2008

320.983'315dc22

2007008757

Printed in the United States of America

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

To the arpilleristas of Santiago de Chile, valiant citizens who dared to speak against the silence and the shadow, who created life and dignity in tapestries made from leftover cloth. This book is a tribute to their legacy and to their vision of justice.

Foreword

Isabel Allende

Most women are natural weavers of stories, not only those who have the good fortune to be published, but all those who perpetuate the oral traditionmothers, grandmothers, and great-grandmothers who share their secrets while stirring soup, sowing fields, or mending fishing nets. They record the truths of historynot the struggles for power or the vanity of emperors, but the pains and hopes of everyday life. Sometimes, however, even the oral tradition is threatened because a people is deprived of its voice. This was the case in Chile between 1973 and 1989, during the long dictatorship of General Pinochet that followed three years of a Socialist experiment under President Salvador Allende.

The military dictatorship used terror to govern. Censorship, curfew, exile, prison, torture, and desaparecidos people taken by the police and never seen againbecame a way of life for many Chileans. At a terrible social and political cost, the military created a capitalist market but failed to balance it with rights for the workers. They produced the conditions for economic growth on the backs of the underprivileged, who were treated as the disposable sector of the population. In the name of economic efficiency, the generals opposed democracy as a foreign ideology and replaced it with a doctrine of law and order: the law of the strongest and the order of the barracks. Poor women in the shantytowns were the main victims of the new regime. Thousands of them became the only providers in their homes, as their husbands, fathers, and sons disappeared or roamed the country looking for menial jobs. Repression destroyed their families, extreme poverty paralyzed them, and fear condemned them to silence. In these hard circumstances, a unique form of protest was born: the arpilleras , small pieces of cloth sewn together, like primitive quilts. Each one of these modest tapestries narrated something about the misery and oppression that the women endured during that time. With leftovers of fabric and simple stitches, the women embroidered what could not be told in words, and thus the arpilleras became powerful forms of political resistance. As Marjorie Agosn says in this moving book, the arpilleras flourished in the midst of a silent nation, and from the inner patios of churches and poor neighborhoods, stories made of cloth and yarn narrated what was forbidden.

When collectors all over the world began to buy and exhibit the arpilleras , the military government calculated the negative publicity and tried to forbid them, confiscate them, and eventually replace them with safe quilts, produced and traded under the supervision of the government. Today, the original arpilleras are in museums and in the hands of a few individuals who bought them before they became collectible works of art. Thanks to Marjorie Agosn, who researched this subject for many years with the rigorous discipline of a scholar and the sensibility of an artist and a political exile, we now have an idea of what this form of folk art is and the conditions under which it was created. She gives us a glimpse of the arpilleras and tells us about the heartbreaking losses and the unyielding strength, dignity, and love of the women who made them. Agosn validates the experiences of those courageous women, gives them a voice, and saves their stories from oblivion. Like those women and their arpilleras , this book is as subversive and defiant as it is beautiful.

Acknowledgments

This book represents almost two decades of thinking, writing, and listening to the arpilleristas of Santiago de Chile who courageously defied the Pinochet dictatorship. I have met with these women since the early seventies. I was welcomed into their workshops, their homes, and their gardens. I listened to their tales of fortitude and solitude, and learned of courage and dignity amid horrific times. This book would not have been possible without their openness, their prudence, and their kindness. I would especially like to thank Winnie Lira, the coordinator of the arpillera workshops, for her help and guidance. I am grateful to her and to Marvin Home from the New York Times , who wrote one of the first articles about the arpilleras and interviewed me in the eighties, making their work more visible and my life safer. I also want to thank those who guided me as I so innocently worked in a very conflicted political era. In spite of the threats I received both in Chile and outside, and in spite of the menacing letters against my work, I came through the years of the dictatorship with an even greater conviction and commitment to human rights. I thank the arpilleristas of Santiago for making me into a nobler human being who survived beyond fear.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992.