RIVERHEAD BOOKS

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2019 by Margaret Paxson

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Paxson, Margaret, author.

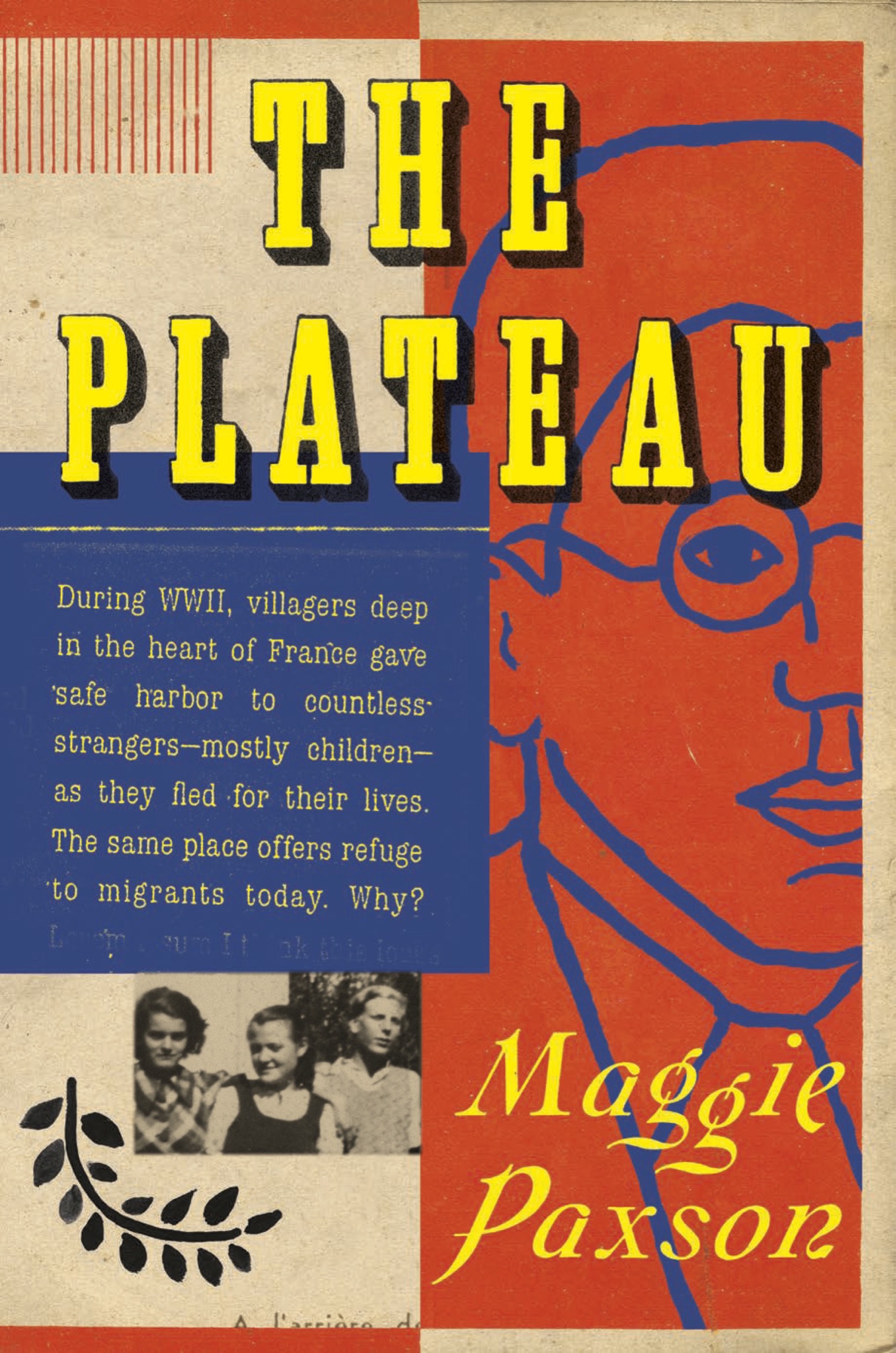

Title: The plateau / Maggie Paxson.

Description: New York : Riverhead Books, 2019

Identifiers: LCCN 2018050747 (print) | LCCN 2019012889 (ebook) | ISBN 9780698408739 (ebook) | ISBN 9781594634758 (hardcover)

Subjects: LCSH: Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (France)Emigration and immigration. | RefugeesFranceLe Chambon-sur-LignonHistory20th century. | RefugeesFranceLe Chambon-sur-LignonHistory21st century. | World War, 19391945RefugeesFranceLe Chambon-sur-Lignon. | Refugee childrenFranceLe Chambon-sur-Lignon. | Le Chambon-sur-Lignon (France) | AnthropologistsBiography. | Paxson, Margaret.

Classification: LCC JV7990.C43 (ebook) | LCC JV7990.C43 P39 2019 (print) | DDC 362.870944/595dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018050747

So much is in a name, but for the sake of their privacy and safetynow and in the futureI have changed the names (and certain identifying features) of the people who appear in the present day in The Plateau, with the exception of public figures and published historians. To mitigate the loss, I have renamed each person with a name, attribute, color, or sound that I love. Ive also tried to preserve in the spelling something of the languages of the names origins. For example, in Chechen, a language with a complex sound system, the consonant transcribed as kh comes in a few forms, but if you hear the Hebrew chai in your head, as in Hanukkah (or even the ch as in the Scottish Gaelic loch), its close enough; dzh is more or less an English j; and so on.

Version_1

For Charles and, in memoriam, for Daniel.

Bright angels.

Il y avait, sur une toile, une plante, la mienne, la Terre, un petit prince consoler!

ANTOINE DE SAINT-EXUPRY , Le Petit Prince

Chapter 1

UNANSWERED

I Daniel was grieved in my spirit in the midst of my body, and the visions of my head troubled me.

DANIEL 7:15

L ET S JUS T SAY THAT suddenly you are a social scientist and you want to study peace. That is, you want to understand what makes for a peaceful society. Lets say that, for years in your work in various parts of the world, youve been surrounded by evidence of violence and war. From individual people, youve heard about beatings and arrests and murders and rapes; youve heard about deportations and black-masked men demanding peoples food or their lives. Youve heard about family violence and village violence and state violence. Youve heard these stories from old women with loose, liquid tears; from young men with arms full of prison tattoos.

There were men on horseback calling the boys to war, and long black cars arriving to steal people away in the dead of night; girls whod wandered the landscape, insane after sexual violations; there was the survival of the fittest in concentration camps; there were pregnant women beaten until their children were lost, and bodies piled up in times of famine; there was arrest and exile for the theft of a turnip; there were those who were battered for being a Jew or a Christian or a Muslim or a Bah.

Lets say that, in the world of ideas that swirled around you, approximations were made of how to make sense of this mess: the presence of certain kinds of states; the presence of certain kinds of social diversity; the presence of certain kinds of religion. And lets say that the shattering stories had piled on over the years until, at some point, you just snapped. You wanted to study war no more.

As it turns out, its harder to study peace than you might think.

Or it has been for me. Im an anthropologist who spent years living among country peoplemostly in a couple of tiny villages in Russiaasking basic questions about how memory works in groups. I had some ideas about how I might start a search for peace. After all, even though the stories of violence were many, for the most part people seemed occupied with other things: They worked in kitchens or fields, hauled water, made decisions about what to do based on the weather, ate with guests, cleaned up after livestock. Even if they bristled sometimes, people generally faced each other day to day with working problems and working solutions. There was love and there were revelries and heartbreaks. And in spite of what theyd seen in life, or what their very own hands might have wrought on their worst days, people saw themselves as basically decent, and expected basic decency back from the world.

Surely, there had to be ways of looking for that kind of eye-to-eye decency. Surely, there were ways to study its power and its limits, particularly when people were faced with tempestuous times. Were there communities out there that were good at being good when things got bad? In my research on memory, Id studied practices of resistance and persistence. Could there be communities that were somehow resistant to violence, persistent in decency? I didnt know exactly what I was on to, but I knew I wanted to study it. In shorthand, I called it peace.

But peace was hard to find. I dug into contemporary scholarship in anthropology, sociology, and political science; I went through databases and bibliographies and talked to colleagues who had been in the trenches with me in the study of a tumultuous Eurasia, and to other colleagues in peace studies programs or peace institutes. What I found was this: There is vastly more contemporary social science on violence than there is on peace. And most contemporary empirical research that says it is about peace is really about conflict. About resolving conflict, cleaning up after conflict, about programs to bring aid to people in conflict settings. About law and justice within the context of conflict. On the whole, these literatures are about peace only insofar as they point to the suffering of millions, and lament.

This kind of work is important, but it wasnt what I was looking for. I wanted social science that landed smack on the inside of peaceful societies and studied human interactions at ground level there, distilling something about how peace works in its tight mechanics. I wanted empirical research that regarded the social body up close and asked about its long-term health and stability; research that asked how, in hard times, regular decency can sometimes translate into extraordinary kindness. Here and there I found brilliant examples of work like this, but strikingly few of them.