Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Those Who Know Dont Say

JUSTICE, POWER, AND POLITICS

Coeditors

Heather Ann Thompson

Rhonda Y. Williams

Editorial Advisory Board

Peniel E. Joseph

Daryl Maeda

Barbara Ransby

Vicki L. Ruiz

Marc Stein

The Justice, Power, and Politics series publishes new works in history that explore the myriad struggles for justice, battles for power, and shifts in politics that have shaped the United States over time. Through the lenses of justice, power, and politics, the series seeks to broaden scholarly debates about Americas past as well as to inform public discussions about its future. More information on the series, including a complete list of books published, is available at http://justicepowerandpolitics.com/.

Those Who Know Dont Say

The Nation of Islam, the Black Freedom Movement, and the Carceral State

Garrett Felber

The University of North Carolina Press CHAPEL HILL

The publication of this book was supported in part by a generous grant from the William R. Kenan Jr. Charitable Trust.

2020 Garrett Felber

All rights reserved

Set in Merope Basic by Westchester Publishing Services

Manufactured in the United States of America

The University of North Carolina Press has been a member of the Green Press Initiative since 2003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Felber, Garrett, author.

Title: Those who know dont say : the Nation of Islam, the Black freedom movement, and the carceral state / Garrett Felber.

Other titles: Justice, power, and politics.

Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [2020] | Series: Justice, power, and politics | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019019411| ISBN 9781469653815 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653822 (pbk : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781469653839 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Nation of Islam (Chicago, Ill.)History. | Black MuslimsHistory. | Discrimination in criminal justice administrationUnited States. | Justice, Administration ofUnited StatesHistory. | Black nationalismUnited States.

Classification: LCC BP221 .F45 2020 | DDC 297.8/7dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019019411

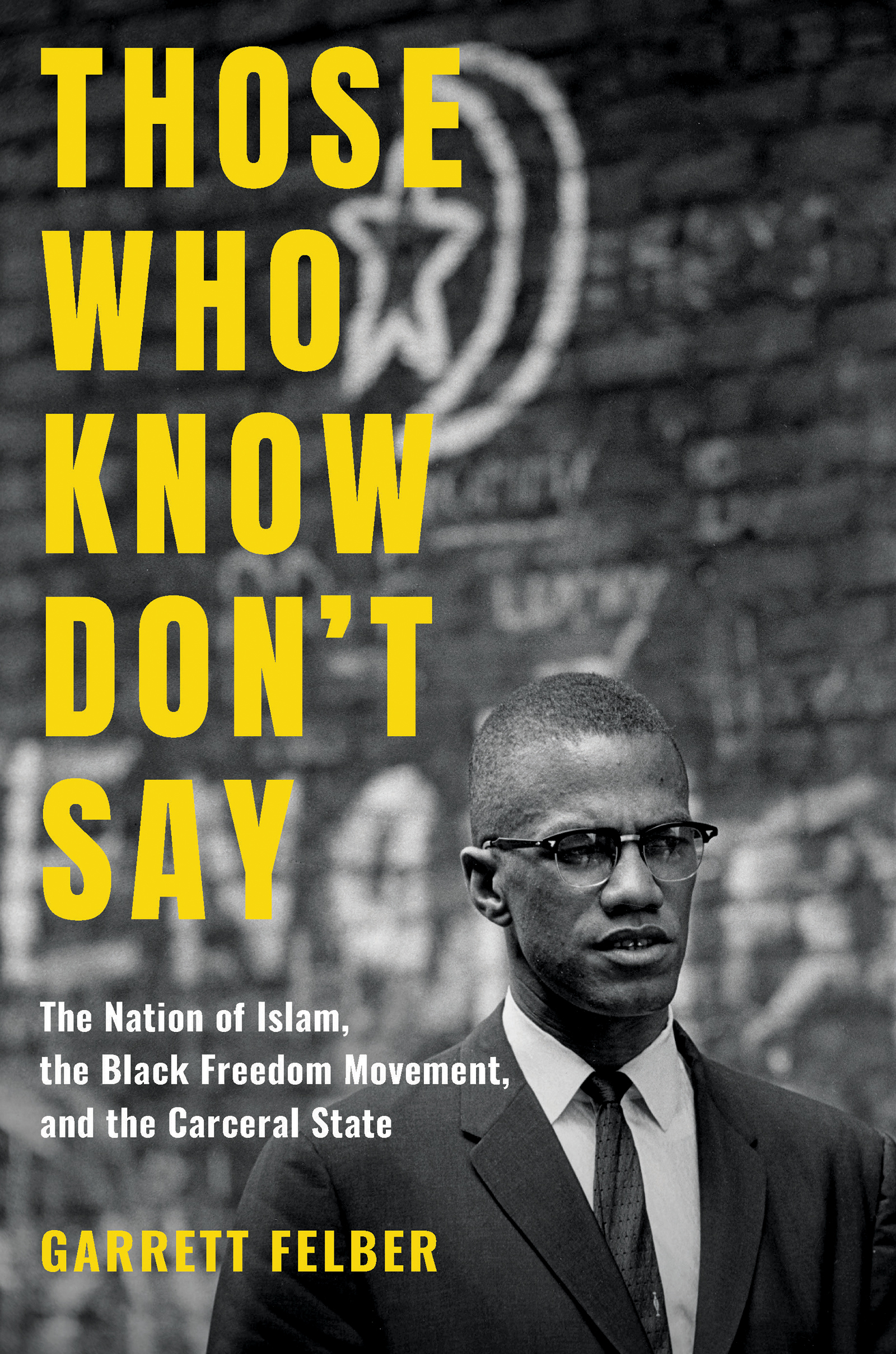

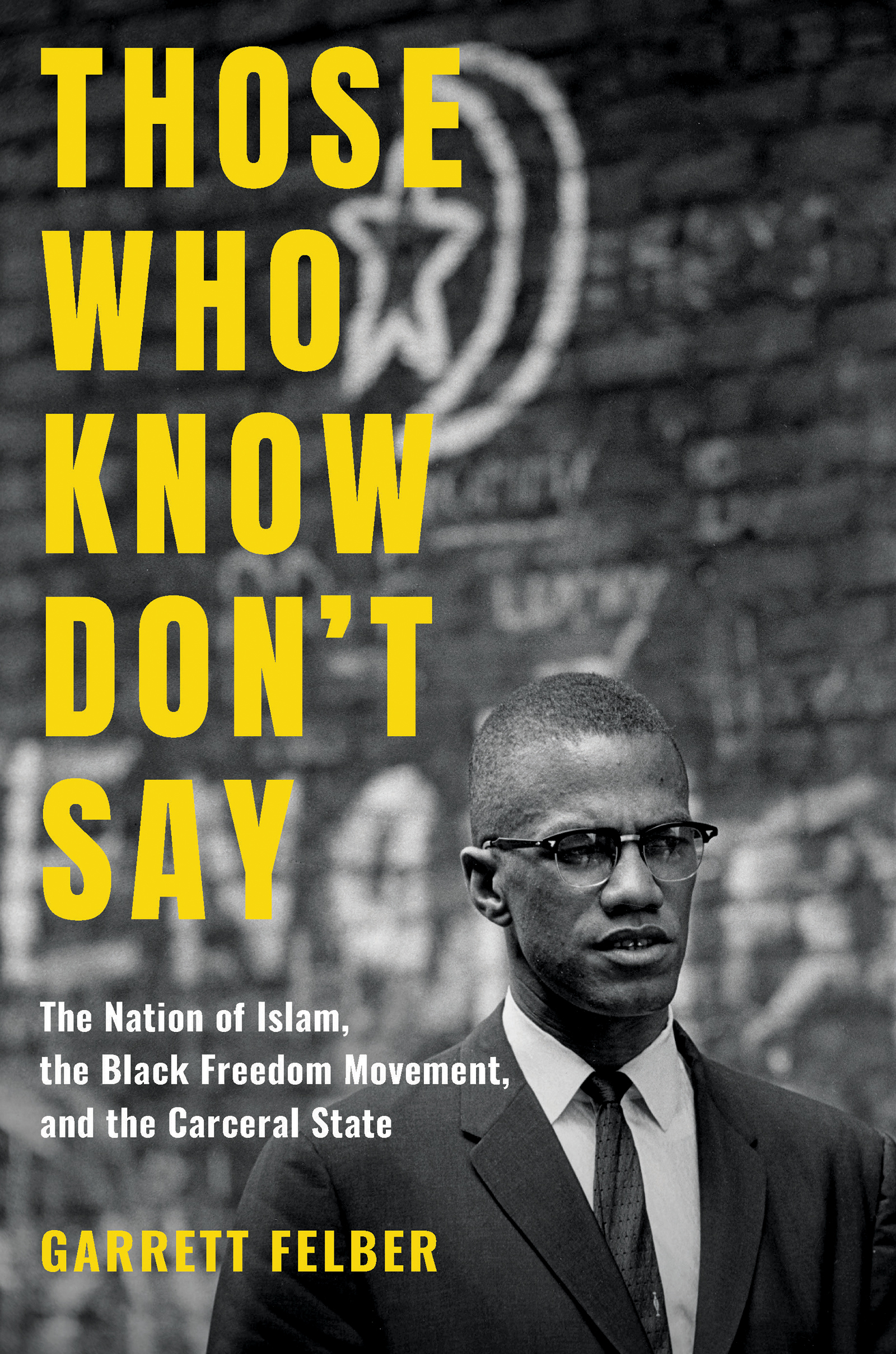

Cover illustration: Malcolm X with star and crescent in the background. Photo by Richard Saunders. Richard Saunders Collection, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library.

Chapter 2 was previously published in a different form as Shades of Mississippi: The Nation of Islams Prison Organizing, the Carceral State, and the Black Freedom Struggle, Journal of American History 105, no. 1 (June 2018): 7195.

For Dr. Manning Marable (19502011),

who set me on this path

Contents

Illustrations

Those Who Know Dont Say

Introduction

On the evening of April 27, 1962, patrolmen Frank Tomlinson and Stanley Kensic stopped Monroe X Jones and Fred X Jingles as they unloaded clothing out of the back of a Buick by the Nation of Islams mosque in South Los Angeles. The ensuing altercation with police, dubbed a blazing gunfight and a riot by the Los Angeles Times, ended with seven unarmed Muslims injured and one dead. In both instances, Muslims in the Nation of Islam (NOI) confronted with police violence and state surveillance, responded with nonviolent protest in the form of prayer.

Where do such stories fit within our narrative of the civil rights era? These episodes demonstrate that challenges to policing and prisons were central to the postwar Black Freedom movement, and the Nation of Islam was at the forefront of that struggle. They show Black Nationalism as an ideological current of Black politics, which continued to gain strength in the years between the dissolution of the United Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) in the interwar period and the rise of Black Power in the late 1960s, a period portrayed as Black Nationalist decline. No group signified and catalyzed this growth more than the NOI. Popular understandings of the NOI have long characterized the group as insular, violent, apolitical, and religiously heretical. It is for these reasons, we are told, that Malcolm X left the NOI to join the civil rights struggle and practice orthodox Islam.

But far from being apolitical, Muslims were ambitious in the pursuit of political goals. They sought to build all-Black coalitions against police brutality and fought for the constitutional rights of prisoners. The circumstances surrounding Ronald Stokess murder in Los Angeles and performative prayer under surveillance at Folsom were not anomalies, but culminations of broader, more sustained campaigns against policing and prisons. To combat the formidable challenge posed by this disciplined Black Nationalist organizing, the carceral state responded with new modes of surveillance, punishment, and ideological knowledge production. This relationship between disciplined, collective Black protest and escalating punitive state disciplinewhich I call the dialectics of disciplinelaid the groundwork for the modern carceral state and the contemporary abolition movements that oppose it.

These dialectics played out in prisons, courtrooms, and the streets. Prison officials tried to stamp out Muslim practice and activism through transfers, solitary confinement, and loss of good time credit, and prisoners countered with hunger strikes, sit-ins, and litigation. In cities across the country, police scrutinized and monitored the growth of Muslim mosques; hassled men selling the Nation of Islams newspaper, Muhammad Speaks; and prepared officers for the inevitability of violent encounters. In addition to responding to provocations with prayer, the NOI marched on police precinct headquarters and filed lawsuits alleging police brutality, which sometimes led to successful settlements. More often as defendants rather than plaintiffs, the group used courtrooms to stage political theater and put the state on trial while building broad-based coalitions in communities of color. The dialectics of discipline describe the interplay between Muslim responses to state repression and the paradoxical acceleration of the expansion of the carceral state through new technologies of violence. Those Who Know Dont Say uses these dialectics as a way to demonstrate the historical process by which the Black Freedom movement and the carceral state were always in dynamic interplay.

Discipline here has a dual meaning: as a means of social control and coerciveness by the state, and as the individual and collective behavior necessary to resist and defeat it. On one hand, what has been called the twin mechanism of police and prisons worked to segment, manipulate, and discipline those the state identified as delinquent or dangerous. There were also methods of internal discipline within both the mosque and the prison, such as silencing, reprimand, and expulsion. Malcolm Xs eventual ouster from the Nation of Islam was preceded by a commonplace procedure of three months public silencing and removal from the community. And when prisoners at Attica in the early 1960s deliberately filled solitary confinement until no more men could be sent there, they met discipline as a means of control with disciplined resistance, thereby undermining its effectiveness as a form of punishment.

This distinction can be seen throughout the NOIs organizing workin its political theorizing as well as in its religious practice. For example, Malcolm X distinguished between racial segregation and racial separation by emphasizing that segregation means to regulate or control. A segregated community is that forced upon inferiors by superiors. A separate community is done voluntarily by two equals. Indeed, discipline was a form of militancy. Discipline enacted by the state was rooted in racial control, coercion, and violence. Muslim discipline was an expression of faith, racial pride, and Black self-determination.