For the thousands whove sacrificed to make a new we possible

And for Al McSurely and Ashley Osment, who trusted the evidence of things not seen

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE

Go Home

LATE AUGUST in North Carolina is harvest time for tobacco growers. Long before the sun rises above the longleaf pines, the air is already thick and heavy in the fields of the eastern sandhills, where I was raised. Men and women roll up their sleeves and bend their backs to prime tobacco, taking the bottom leaves first. I grew up in these fields, listening to the songs people hum when they know theres work to be done and the day is only going to get hotter. Some days I still wake up humming those songs.

August 28, 2013, I woke up at home in North Carolina. It had been a long, hot summer, and my body was tired. But as a mother of the church in Montgomery, Alabama, famously told Dr. Martin Luther King during the bus boycott, even though my feet were tired, my soul was rested. I woke up that morning humming a song I learned from mothers of the church in eastern North Carolina.

Ive got a feeling everythings gonna be all right.

Oh Ive got a feeling everythings gonna be all right.

Ive got a feeling everythings gonna be all right.

Be all right, be all right, be all right.

Four days before, Id been in Washington, DC, for the national commemoration of 1963s March on Washington. Fifty years after that historic day when millions of Americans heard Dr. Kings dream on national television for the first time, civil rights leaders from around the country gathered to commemorate the achievements of freedom fighters who gave so much half a century ago to guarantee the opportunities we often take for granted today. I sat alongside a great hero of that era, Julian Bond, commenting on the days celebrations for Melissa Harris-Perry on MSNBC.

But as soon as the festivities were over, I knew I had to go home.

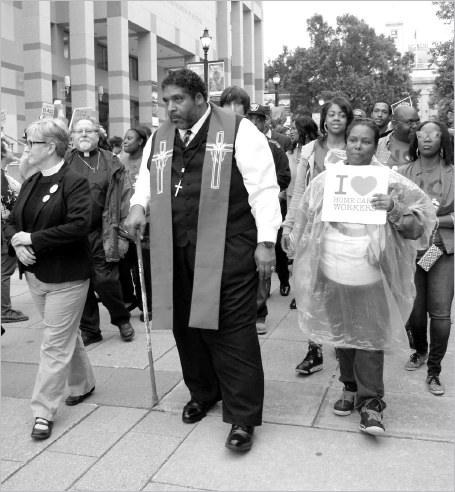

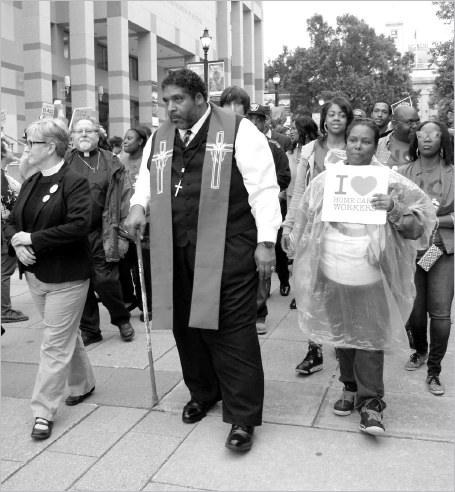

I had been invited to go to Washington because Moral Mondays had gained national attention during that summer of 2013. On April 29, 2013, sixteen close colleagues and I had been arrested at the North Carolina statehouse for exercising our constitutional right to publicly instruct our legislators. We did not call it a Moral Monday when we went to the legislature building that day. In fact, it took us nearly three weeks to name what started with that simple act of protest. But when a small group of us stood together, refusing to accept an extreme makeover of state government that we knew would harm the most vulnerable among us, it was like a spark in a warehouse full of cured, dry tobacco leaves.

The following Monday, hundreds returned to the statehouse and twice as many people were arrested. Word of a mass movement spread among justice-loving people throughout North Carolina, igniting thousands who knew from their own experience that something was seriously wrong. Throughout the hot, wet summer of 2013, tens of thousands of people came for thirteen consecutive Moral Mondays. By the end of the legislative session, nearly a thousand people had been arrested in the largest wave of mass civil disobedience since the lunch counter sit-ins of 1960.

Those Moral Monday rallies were on my mind as I hummed the old spiritual that late August morning. Fifty years earlier, in Indianapolis, Indiana, my mother had gone into labor on this very day. The joke in my family is that I, the child in her womb, heard that people were marching for jobs and justice in Washington, so I decided to wait for them before my entrance into the world. By the time I was born two days later, my parents friends and coworkers who had made the long trip to Washington were back home. They had heeded Dr. Kings words:

Go back knowing that somehow this situation can and will be changed.

Going back home, they did the painstaking work of building communities committed to justice, educating neighbors about issues that affect the common good, and organizing poor people to register, vote, and speak out in their communities. As inspiring as Dr. King was, historians are clear that it was not him alone, but rather the thousands of unnamed people like my parents who turned the tide in America after the March on Washington, guaranteeing the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and, after Bloody Sunday in Selma the following spring, the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In fact, it was my fathers commitment to go home and labor in forgotten fields that led him and my mother to return to North Carolina in the late 1960s, sending me to integrate the public schools in Washington County. I was drafted into the justice struggle before I ever had a chance to know anything else. I learned to be a freedom fighter by going home.

Half a century later, I found myself a leader in the reemerging Southern freedom movement, trying to understand a mass movement that had erupted in response to twenty-first-century injustice in my own home state. Moral Mondays had not just happened. They resulted from the efforts of 140 organizations that had worked together as a grassroots coalition for seven years. When crowds chanted, Thank you! We love you! each week to the scores of arrestees leaving the legislature building in Department of Corrections buses, they were cheering on their pastors, their union leaders, their professors, and their grandmothers. We didnt just know one another. We were family.

But as much as I knew the people and understood the long, hard organizing work that had made Moral Mondays happen, I did not know how to explain this sudden explosion of resistance. Though it grew out of the familiar ground of freedom, something new was happening before our eyes. Like our foreparents who marched on Washington, we in North Carolina were caught up by the zeitgeist in something bigger than ourselvessomething bigger, even, than our understanding. But we knew one thing without a doubt: we had found the essential struggle of our time. Inspired by nothing less than Gods dream, we were ready to go home and do the long, hard work of building up a new justice movement to save the soul of America.

So I was at home on August 28, 2013that Wednesday when we looked back to remember the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington. Our Forward Together Moral Movement held thirteen simultaneous rallies in each of North Carolinas congressional districts that day, bringing together tens of thousands of people who had been mobilized for action through Moral Mondays. We were black, white and brown, women and men, rich and poor, gay and straight, documented and undocumented, employed and unemployed, doctors and patients, people of faith and people who struggle with faith. We were, it seemed to me as I drove between rallies in Greensboro, Lincolnton, and Charlotte, a glimpse of Dr. Kings dreamof the republic that, though promised and longed for, has never yet been. Baptized in the fires of mass demonstration, we were a fusion coalition of people committed to reconstructing America itself.

On national television, the networks broadcast commemorative speeches and historical reflections on Dr. King and the civil rights movement. Much of it was interesting history, Im sure. But I witnessed something far more inspiring at home in North Carolina on the fiftieth anniversary of the March on Washington. I came home to the beginnings of a Third Reconstruction. After Americas First Reconstruction was attacked by the lynch mobs of white supremacists in the 1870s, it took nearly a hundred years for a Second Reconstruction to emerge in the civil rights movement. Though we ended Jim Crow segregation in the 1960s, structural inequality became more sophisticated in the backlash against the movements advances. We have a black man in the White House that was built by slaves, but the wealth divide that is rooted in our history of race-based slavery is more extreme than it ever has been. Nothing less than a Third Reconstruction holds the promise of healing our nations wounds and birthing a better future for all. But were not just waiting for it. Weve seen what it looks like.

Next page