Table of Contents

I did not care what or where I were at. I ask God to help me

and he did so, and that is how I came through that

terrible and hell place for the whole entire battle field were hell.

So it were no place for any human being to be.

HORACE PIPPIN

Preface

The last French veteran of World War I, Lazare Ponticelli, was born December 7, 1897, in Bettola, a town in northern Italy, and died on March 12, 2008, at the age of 111. The last German veteran, Erich Kaestner, died on New Years Day 2008 at the age of 107. Three British veterans are still alive at the time of this writing, though they may not be by the time this volume is published: a 107-year-old named William Stone, a 109-year-old named Harry Patch, and a 111-year-old named Henry Allingham. In the United States, one veteran, Frank Woodruff Buckles, 107 now but only 15 years old when he joined the U.S. Army, is still alive. Of the remaining veterans, Harry Patch did not speak of the war until he was 100 years old, when a flash of light beyond his bedroom window brought the memories back, and he began to discuss his wartime experiences, the feelings of being paralyzed by fear, eaten alive by lice, surrounded by death, and sick of it all. Soon, no one will be left to give a first-person accounting of what happened during the war, and only then will the war truly be over.

The irony of the First World War, dubbed the War to End All Wars, is not that it failed to end all wars, if anybody believed that P. T. Barnum-ism in the first place, but that something terrible enough to generate such hyperbole has fallen so far from the collective American consciousness. For baby boomers, World War I ended thirty to thirty-five years before we were born and seemed part of ancient history, though events thirty years ago today dont seem very distant at all. We may have seen a few souvenirs or photographs in our grandfathers dens, watched old men marching in Fourth of July, Memorial Day, or Armistice Day parades, or perhaps accompanied our parents on visits to nursing home ice cream socials where veterans of the First World War sat on benches eating spumoni and drinking lemonade from paper cups. We might think we know about the First World War, but how many of us can say what it was about, or who the Central powers were, or how it reshaped the world we live in as arguably the most transformative event of the twentieth century?

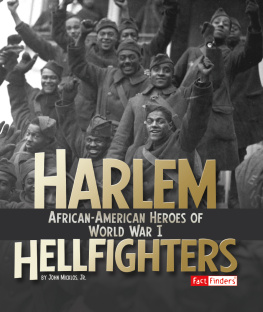

One cant say it went undocumented. Much has been written about the war, not just by historians but also by poets like Siegfried Sassoon, Wilfred Owen, Rupert Brooke, David Jones, and others; it is depicted in the prose of Robert Graves, Edmund Blunden, and Ernest Hemingway, as well as in that of German writers like Georg Trakl or Erich Maria Remarque. It might be that the war has faded from memory partly because so much has been written about it that we think the record is complete; we can file it all away, look it up if we need to, and move ahead if we want. This book tells the story of a group of men who fought in World War I but could not be forgotten because they were never fully known. Part of the reason was that although they were Americans, they were loaned to, and fought as part of, the French army. The rest of the reason is that they were African Americans, whose history went largely untold (or untaught) until the second half of the twentieth century. They were men primarily from New York and the upper East Coast who volunteered for duty at a time when a large portion of the country did not want to get involved in a war so brutal and so far from home. They formed in 1916 and were, at first, simply the Fifteenth New York National Guard, a title they preferred even after they became the 369th U.S. Infantry Regiment to the War Department, the 369th RIUS to the French, and eventually the Harlem Hellfighters to the Germans.

In a war where the vast majority of the black soldiers served in the Service of Supply, unloading ships and building roads and railroads, the men of the 369th trained and fought side by side with the French at the front and ultimately spent more days in the trenches, 191, than any other American unit. They also went to war (and many paid the ultimate price) in defense of a country that did not defend them, a country at the time widely afflicted by segregation, Jim Crow laws, lynchings, and racial violenceyet a country they managed to believe in all the same.

The men of the 369th altered historys course, but too often, histories make soldiers seem like active players in a larger sociopolitical drama. The men who became known as the Harlem Hellfighters were just ordinary men in extraordinary circumstances, men with families, with wives and children, and with plans for after the war. If they had a sense of the part they were playing in the larger socio-political scheme, it was on the level of faith rather than anything they knew for certain. They rarely knew what was happening in the war itself, beyond their small section of the line. They lived in a very proscribed and finite world. To tell their story is to name the things they would have seen and heard and smelled and felt and to show how it changed them. More than that, however, it is to remind the reader that by standing up for what they believed in, what they thought was right, they created a narrative about good men who did something brave and noble when they had every reason to turn their backs on a country that had too often turned its back on themits a story about pride and honor and a struggle on two fronts, one in France and one at home. Of the first front, only a handful of very, very old men remain who can tell of it. Of the other struggle, the story is still alive and ongoing.

one

Parades

Over in France theres a game thats played

By all the soldier boys in each brigade

Its called Hunting the Hun

This is how it is done!

First you go get a gun

Then you look for a Hun

Then you start on the run for the son of a gun

You can capture them with ease

All you need is just a little Limburger cheese

Give em one little smell

They come out with a yell

Then your work is done

When they start to advance

Shoot em in the pants

Thats the game called Hunting the Hun!

ARCHIE GOTTLER AND HOWARD E. ROGERS,

HUNTING THE HUN, 1918

In the summer of 1916, it was not uncommon to see military parades assembling outside the Lafayette Theater on Seventh Avenue between 131st and 132nd streets in the heart of Harlems club and theater district. War was in all the papers. It was in the air. It was not our fight, but how could we avoid it? Americans of all races needed to be ready, although it was a war no one could adequately prepare for.

The first parades were relatively motley affairs and served a dual purpose. One was to turn citizens into soldiers. Teaching discipline, obedience, and unit cohesion, the parades forced the men to practice and memorize military behaviors until they became instinctive, following a martial tradition where soldiers fought in formation, on battlefields where organized troops conquered and dispatched disorganized opponents. The war they were preparing for in France was changing all the old rules, but order was still preferable to chaos.