To Linda and Sandy Kauffman, who have nourished me in ways I appreciate more with every day

Contents

The Sunlight Cafe, Seattles oldest-surviving vegetarian restaurant, has been around for so long now that my lunch there is as familiar as it is a target for ridicule.

Cubes of sweet potato and Us of celery bob on the surface of a chunky Mexican bean fiesta soup, the scent of cumin surfing on the steam rising off its surface. Alfalfa sprouts jut out of an avocado-havarti sandwich as if its toasted whole-wheat shell were a squashed-on hat. A side salad is drizzled with tahini-lemon dressing and speckled with sunflower and sesame seeds. Tack on a slice of nutloaf, and youd have a complete 1970s feast, the antithesis of all-American meat and potatoes, the kind of food that would still be associated with hippies even fifty years after San Franciscos Summer of Love.

The Sunlight Cafe, opened in 1977, doesnt deny its hippie heritage. Although Seattles climate often renders its name aspirational, when the sunlight does arrive, it floods the brightly colored room. Native American paintings hang above the wooden booths, and solid-looking whole-wheat cookies and muffins lurk in the pastry case. The sign on the mens restroom depicts a stringy-haired, bell-bottomed dude. I share the same scuffed wood table with several white guys in their sixties reading the Seattle Times over their huevos rancheros and a group of stout, fleece-clad women debating whether theyre going to order the tempeh or the tofu burger because both sound soooo good.

These are my people. This is the food I have been surrounded by all my life.

For those of you who didnt grow up eating lentil-and-brown-rice casseroles, it may be hard to recognize what came to be called hippie food. Thats because so many of the ingredients that the counterculture of the 1960s and 1970s adopted, defying the suspicion and disgust of the rest of the country, have become foods many of us eat every day.

The organic chard you bought at Kroger last week? In the early 1970s, farming organically was considered a delusional act. The granola-yogurt parfait your coworker just picked up at Starbucks? In 1971, both granola and yogurt were foreign substances, their reputation as tied to long-haired peaceniks as pour-over coffee is to lumberjack beards and high-waisted jeans. Back then, whole-wheat bread had disappeared from grocery stores. Hummus wasnt a childhood staple but a dish only spotted in Middle Eastern markets and vegetarian cafs.

The cuisine that the counterculture took to in the late 1960s, and then helped introduce to the mainstream in the 1970s, embraced whole grains and legumes; organic, fresh vegetables; soy foods like tofu and tempeh; nutrition boosters like wheat germ and sprouted grains; and flavors from Eastern European, Asian, and Latin American cuisines. The food young bohemians concocted with all these ingredients was often vegetarian, sometimes macrobiotic, and occasionally inedible.

Forty years on, people who didnt live in that era might assume that hippie food could only be found in big cities and rural communes, but that wasnt the case. I grew up in the 1970s, in a Mennonite community in Elkhart, Indiana. We only ate the traditional Pennsylvania Dutch fare of our grandparentssauerkraut, funnel cakes, shoofly pieonce or twice a year. At my parents house, dinner was likely to be stir-fried tofu and broccoli one night, lentil stew the next.

Ultraliberal Mennonites like my parents were hardly Plattdeutsch-speaking, covering-wearing Amish. Yet the community I was raised in was no commune, either. My dad did sport lush sideburns, and my parents politics were left of George McGoverns, but even the leftiest Mennonites raised their kids on hymns and social justice activism rather than Sympathy for the Devil and key parties.

In 1976 a Pennsylvanian named Doris Janzen Longacre changed the diet of my parents, their friends, and all my Sunday school classmates with the publication of the More-with-Less Cookbook. Informed by Frances Moore Lapps 1971 Diet for a Small Planet, as well as the experience of Mennonite contributors who had volunteered around the world, recipes in the More-with-Less Cookbook combined whole-grain ingredients with African, Asian, and Central American flavors, garnished with earnest discussions of how to live on a planet with limited resources.

I was five when my mother bought her copy of More-with-Less. She was no purist. Yet for the next decade Velveeta cheese and Frosted Flakes disappeared from our pantry, to be replaced by a host of strange brown substances.

Much of what my friends and I grew up eating in the 1970s had all the characteristics that still define hippie food to me, like oatmeal whole-wheat bread, homemade yogurt sweetened with a spoonful of my mothers own jam, date-pecan granola, West African ground-nut stew, and vegetables pulled from our gardengrown without pesticides or herbicides, of course.

My parents, like many of their generation, eased up on the restrictiveness of the More-with-Less diet as their careers accelerated and their children grew more persuasive. Yet the consciousness around food that the cookbook inspiredof the political significance of what we were eating, of the sense that no cuisine is truly foreign, of the goodness of whole-wheat flour and honeyremained. In fact, it has colored my entire career in food.

So I ask with all earnestness: How can you not love an avocado-havarti sandwich? The gush of the ripe avocado. The crunch of the toasted bread. The intense green flavor of the alfalfa sprouts, which smell as if a field of grass were having sex. To me, lunch at the Sunlight Cafe evokes the same warm-blanket comfort that macaroni and cheese does for other Americans. Lunch here isnt satisfying in the same way that a well-charred steak is. But its satisfying just the same: earthy, fresh, and straightforward.

A decade ago, over a meal of steamed vegetables and brown rice with tahini sauce at the Sunlight Cafe, a thought caught hold: Why didnt I accept hippie food as a unique, self-contained cuisine? Why did I treat it as an outdated curiosity, instead of giving it the same respect and attention I did Vietnamese pho shops and French bistros? As I mulled the idea over, two more questions arose: Why did the counterculture start eating foods like brown rice, tofu, granola, and whole-wheat bread in the 1960s and 1970s? And how did this cuisine spread across the country, reaching a tiny city like Elkhart, Indiana, in a matter of just a few years?

Fifty years on, it may seem inconceivable how revolutionary a stir-fry of tofu and vegetables over brown rice could have been in 1967 and how alienating a havarti-and-avocado sandwich on whole-wheat bread would have seemed to most Americans.

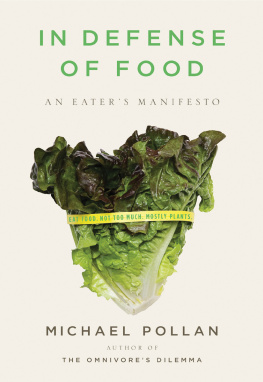

Just for comparison, I picked up a copy of the 1963 Good Housekeeping Cookbook at a used-book store. It contained 166 pages devoted to meat dishes and 138 pages of desserts, compared to just 79 pages for salads and vegetables. Adventurous

Although the nineteenth century and early twentieth century saw the invention of canning, freezing, and other methods of processing food, World War II marked a turning point in American manufacturers ability to manipulate our food into forms never seen in nature. Out of the war came

Those advances merely set the stage for a postwar boom in agriculture,

The American diet changed drastically as well. Per capita meat consumption rose by a third between 1950 and 1965, and chicken, pork, and beef replaced eggs, dairy, and grains on the plate. tailored to these humongous new stores. Grocery chains added rows and rows of shelves to fill with boxes, bags, and cans.

Middle-class Americans could pile their wheeled grocery carts high: the average wage was rising even as food was getting cheaper. Between 1960 and 1972, household spending on food dropped from 24 percent to 19 percent, and it would

![Blackstone Audio Inc. - The politically incorrect guide to the presidents: [from Wilson to Obama]](/uploads/posts/book/167736/thumbs/blackstone-audio-inc-the-politically-incorrect.jpg)