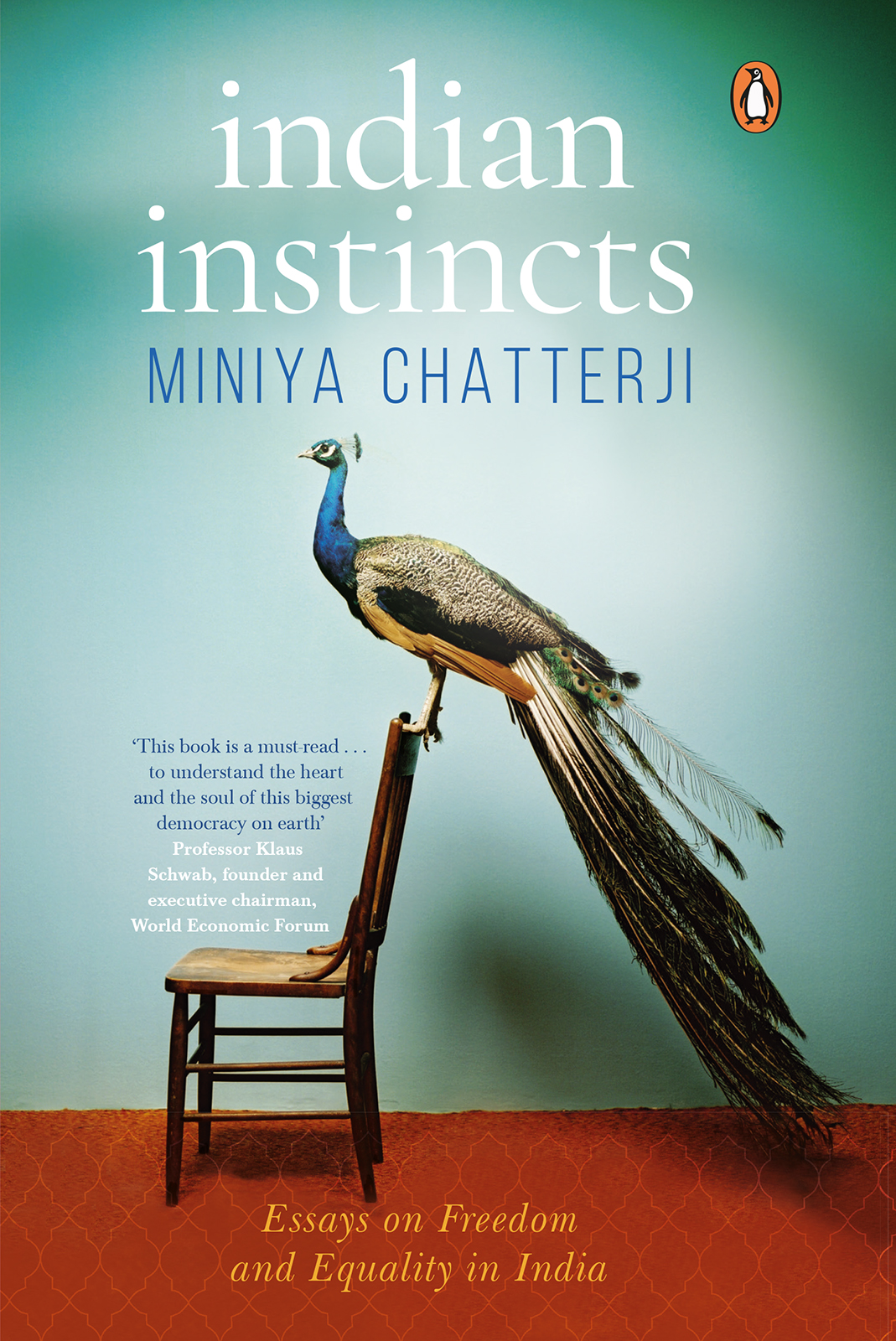

Introduction

D uring the course of writing this book, I became a parent. I watched with amazement as my baby boy, fresh out of my womb, learnt the need and technique of suckling, for surviving in his new environment. I found that he was not endowed with any primordial instinct to suck on my breast, but he learnt. Thus began his journey, wherein he would use his rational faculty to learn skills to survive in this world.

Survival is a primordial instinct, but most of our instincts or the spontaneous behaviours that we display are not innate. In fact, to deny this is to accept that a persons character is inherited, which is the basis of every xenophobic argument. Instead, I believe that instincts are a spontaneous rationality (or irrationality) developed by our cognitive faculty in response to the environment. And the development of this rationality is volitionalwe must want it, nurture it, and learn how to use it.

Thus, there is no predetermined Indian instinct. In India, our spontaneous behaviour is a rational (or irrational) choice under the overwhelming influence of politics, ambition and religious fervour in the environment.

In every era and everywhere, governance structurestribes, kingdoms, nation stateswere created to provide resources such as food, shelter and safety for the people. Now, in India, we are besotted with the latest news, views, analyses and Twitter wars on party politics instead of the resources the state must provide. We created the concept of corporations and jobs so that we could earn ourselves a comfortable life, but it turns out that often the first half of our life is overpowered by the quest for building a curriculum vitae for a job, and thereafter by the inimitable 24/7 Indian corporate culture. Similarly, we invented religion as a framework by which to lead our lives, yet blinded by our faith we kill each other. A recent survey gives India a high rank in terms of religious hostility, putting it in the company of Syria, Nigeria and Iraq.

This is why a certain hypothesis has haunted me for several yearsthat we are willingly entrapped in the institutions of our own making, having abandoned the rationality to realize that we have lost sight of the reasons these institutions were set up in the first place.

The central theme of this book is that, in India these institutionsthe government, corporation, religionhave often become sources of the problem, increasing economic inequality and curbing our free will. It is to this environment that we Indians respond, sometimes with rationality and sometimes without. The fifteen essays of this book hold up a mirror to what we have thus become.

This book is not one that could have been written merely sitting at my study desk. Instead it is a consequence of taking on lifes adventures. For this, I thank my parents and my brother for supporting three decades of my unlikely choices. I thank Chirag for sweeping me off my feetthis book is because of him, for him. Thank you, Naveen, for your friendship and for giving me wings in India. Laxman and Rajshree, thank you for your generosity. Sayem, thank you for showing me life. Neelini, I am grateful for your edits. Milee, thanks for your friendship, advice and patience.

1

Survival

A lmost 200 years ago, the Swiss-born natural historian Louis Agassiz invented the premise for every xenophobes favourite argument. He said that the three major human racesWhites, Asians and Negroes, as he liked to categorize themhad risen independently from separate ancestral lineages. Agassiz declared.

As a professor at Harvard University, Agassiz was one of the first to propose that Earth had endured an Ice Age, but he also used his public stature as a scientist to prove racism. It was the era of scientific racism, which meant that there were others such as Samuel George Morton who used various so-called scientific methods to rank human races.

Fortunately for us, Agassizs argument was debunked by his contemporary from the other Cambridge, in the United Kingdomthe academic Charles Darwin. Darwin suggestednow famouslythat all of us had descended from one common ancestor in Africa.

But Darwin had actually spoken about apes, not modern man. Moreover, if we go back far enough, we will see that humans share a distant common ancestry with every living thing on Earth, including bacteria and mushrooms. Therefore, it might be more relevant to find out what happened after the first exodus of apes from Africa took place sixteen million years ago. Many apes left for South-East Asia to evolve into gibbons and orangutans, and the ones who stayed on in Africa evolved into gorillas, chimpanzees and humans.

So what happened after that? How did humans not only survive in Africa from that point onwards, but also go on to inhabit the rest of the world? And if we all have descended from that one human in Africa, why do we talk about race? Why do we believe that people belonging to specific nationalities, religions and ethnicities display common characteristics, and that each such community is different from the others?

In India, thousands of diverse local communities are defined by the conviction that there is something unique shared among the people of a particular community. We assume that we must naturally display some characteristics of the community to which we are connected by blood and heritage.

This belief among Indiansthat we display a set of settled characteristics because of our membership by birth to a certain communityhas far-reaching and varied effects on our thinking about ourselves and about others. It gives some of us a sense of mystic belonging to a community. We might believe that our behaviour cant be helped since our mannerisms were predetermined by birth as per that community. We might even forcefully emulate some of the communitys established characteristics to feel divinely connected to it. This could also mean that we are left with hardly any place for choice or individuality.

For example, a Gujarati is supposed to be entrepreneurial by blood. Now, if a young Gujarati boy is told this from the day he can distinguish language from random sounds, that is likely to be the ambition he will grow up withemulating the characteristics of his fellow Gujarati business wizards, and feeling a sense of community bonding. Similarly, when a Parsi or a Sindhi meets another Parsi or Sindhi for the first time in any corner of the world, there is often an immediate sense of familiarity and trust between them. The bond between two members of the same community is often accompanied by a willingness to help the other out. To cite another example, the cultural clich is that Bengalis are good at the arts, that they make good writers, musicians, painters and so on. How does that clich affect a young Bengali child in Kolkata in terms of the education she or he receives and the expectations from the community? When this child grows up, she or he can probably leverage the instant community bond with fellow Bengalis in creative fields to land a similar job.