ALSO BY CHANDRA MANNING

What This Cruel War Was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War

THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

Copyright 2016 by Chandra Manning

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Manning, Chandra, author.

Title: Troubled refuge : struggling for freedom in the Civil War / Chandra Manning.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A. Knopf, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015039724 | ISBN 9780307271204 (hardcover) ISBN 9781101947791 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865 African Americans. | SlavesEmancipationUnited States. | United StatesHistoryCivil War, 18611865Social aspects.

Classification: LCC E 453 . M 24 2016 | DDC 973.7/11dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015039724

ebook ISBN9781101947791

Map concepts and research by Tom Foley

Additional cartography by Robert Bull

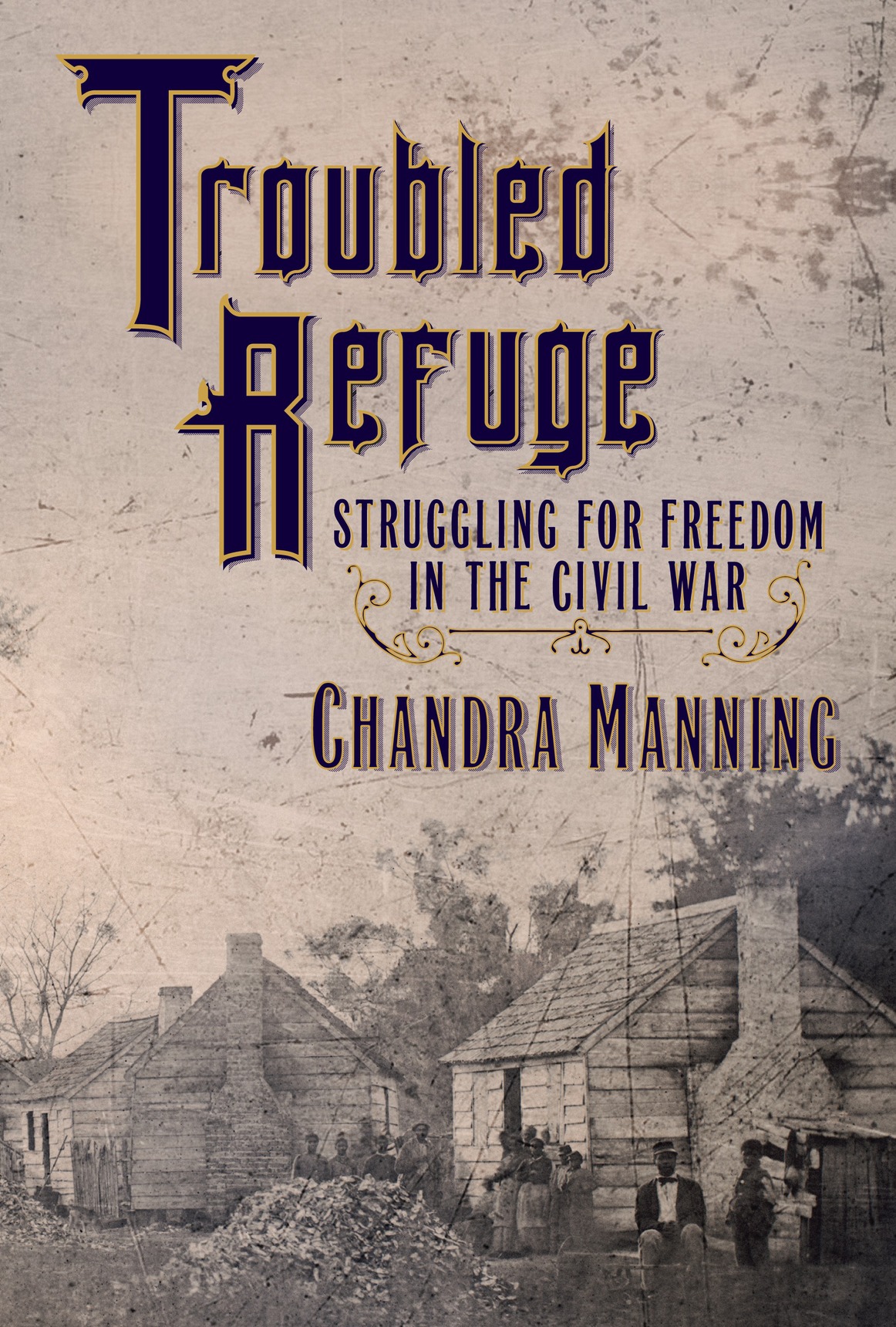

Cover image: Slaves sitting near their cabins on a Port Royal South Carolina plantation by Timothy OSullivan, 1862. Everett Historical/Shutterstock

Cover design by Perry De La Vega

v4.1

ep

Contents

Dedicated to Georgetown

Introduction

I t was August 1862 and mercilessly hot near Fredericksburg, Virginia. Union soldiers in their shirtsleeves were supposed to be on picket duty, but they could barely stand up, even in the shade. As they wilted, they looked on in wonder as more than eighty women and children, barefooted, bareheaded, with nothing to eat, little water, and no protection from the sun, walked with grim determination across a shadeless plain and into Union lines. All were faint and hungry. One womans blouse had been reduced to ribbons by the same whip that had cut her back to pieces. Another womans hair was entirely gray, and her back was so stooped that she walked practically at right angles to the ground, but there was nothing frail about the way she grasped the hand of a little girl about three years old. The old womans daughter had been sold to the far Southern market, and she had been taking care of her granddaughter ever since. Then she overheard her owners plans to ship her to Richmond, leaving her granddaughter with no family to shield her from the violence of slavery. So the woman ran, and she took the little girl with her. The Union soldiers she found were mainly farmers who thought they knew what physical demands on the body were, but in the presence of this woman the men were awestruck. At least one was moved to tears. Wordlessly, they placed their days rations into the hands of the women filing by, knowing that the procession might try to make its way west to the Orange and Alexandria Railroad, or maybe ride the rails from Fredericksburg to the Potomac River and from there get to Washington, D.C. Within Union lines, the women and children could see tracks leading out of slavery. Where those tracks led to was far less clear.

Winter winds along the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers were cold, but the aging man barely noticed. Francis Lieber, Prussian immigrant, veteran of the Napoleonic Wars, famous jurist, and soon to be the author of the Lieber Code, the worlds first written guidelines for military conduct in civilized warfare, was looking for his son. A Union soldier, Hamilton Lieber had gone missing after the February 1862 battle at Fort Donelson in Tennessee. The grim trip was not Liebers first wartime journey. The previous summer, he had visited General Benjamin Butler at Fort Monroe, Virginia, and pondered what the United States ought to do about run-away slaves there. This time, he checked Cincinnati, St. Louis, and Paducah, Kentucky, where a captain in Hamiltons regiment confirmed that the young man was alive last the captain knew. Paducah was full of hospitals and soldiers, as well as of black men and women who had run from their masters, some dashing furtively out of sight in case the unfamiliar white man might be in camp to try to drag slaves back into bondage. Lieber found whole cargoes of wounded, dying and dead loaded onto steamboats and sent downriver, but he did not find his son. He followed the steamboats to Cairo and then on to Mound City, Illinois. Once again, Lieber made his way among refugees from slavery, ducked his head frantically into tents, and strode determinedly up and down rows of hospital beds until finally he found the dear boy, minus one arm, but still alive. Lieber had already known war as [a] soldier, as a wounded man in the hospital, as an observing citizen, but now he knew war as a father searching for his wounded son. Moreover, he was a father who just weeks later would lose another son, his beloved Oscar, who had already broken his heart by joining the Confederate army in this awful war that Lieber hoped would uproot slavery. In that poignant winter, Lieber confronted a central paradox of war: its chaos brought suffering and new possibilities not merely at the same time, but intimately connected to each other.

The Hungarian-born major general Alexander Asboth needed fortifications faster than soldiers could build them. Serving in 1863 as post commander at Columbus, Kentucky, a state that officially stayed in the Union but was filled with civilians who supported the Confederacy, Asboth bore responsibility for defense against guerrillas as well as regular Confederate forces. At first, he hired white civilian laborers, but he found many of them to be the least efficient workers he had ever come across. Meanwhile, black men, women, and children fleeing their Kentucky masters were streaming into his lines, and they proved to be much better workers. Before long, a local civilian, Mrs. V. C. Taylor, insisted that Asboth return slaves who had taken shelter in his camp. The major general refused, on the grounds that she and her husband not only have many relatives in the Rebel Army, but they warmly sympathize with the traitors. No matter how fair Mrs. Taylors complexion was, and no matter how rich she was, she had forfeited any right to protection or indulgence from the U.S. government when she chose to betray it. She went away empty-handed, which to Asboth seemed like a straightforward matter of wisdom and justice, but local civil authorities fought his decision bitterly, and it took constant vigilance to prevent them from kidnapping African Americans and hauling them back into slavery. Moreover, Asboths surprises regarding the black workers were not over yet: it turned out that the laborers were being paid less than the white workers fired for inefficiency had been. Surely, all who would work faithfully or volunteer to fight for our common cause should count the same in the eyes of the government they served, Asboth insisted. He and the black fortification builders had learned that former slaves seeking freedom were likely to get more from military authorities than from civil ones, but that alliance with the Union army came with its own limits and drawbacks.