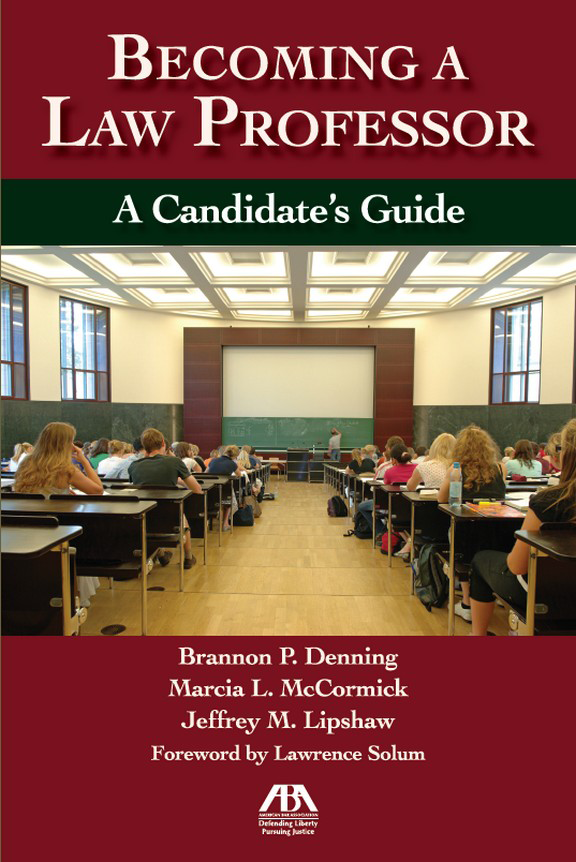

Cover design by ABA Publishing.

The materials contained herein represent the opinions and views of the authors and/or the editors, and should not be construed to be the views or opinions of the law firms or companies with whom such persons are in partnership with, associated with, or employed by, nor of the American Bar Association, unless adopted pursuant to the bylaws of the Association.

Nothing contained in this book is to be considered as the rendering of legal advice, either generally or in connection with any specific issue or case. Readers are responsible for obtaining advice from their own lawyers or other professionals. This book and any forms and agreements herein are intended for educational and informational purposes only.

2010 American Bar Association. All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. For permission, contact the ABA Copyrights and Contracts Department at copyright@americanbar.org or via fax at 312-988-6030.

Printed in the United States of America.

14 13 12 11 5 4 3 2

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Denning, Brannon P.

Becoming a law professor: a candidate's guide/by Brannon P. Denning, Marcia L. McCormick, Jeffrey M. Lipshaw.1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-60442-994-7

1. Law teachersVocational guidanceUnited States. 2. LawUnited StatesStudy and teaching. 3. Law schoolsUnited StatesEmployees. I. McCormick, Marcia. II. Lipshaw, Jeffrey M. III. Title.

KF272.D46 2010

340.071'173dc22

2010042094

Discounts are available for books ordered in bulk. Special consideration is given to state bars, CLE programs, and other bar-related organizations. Inquire at Book Publishing, ABA Publishing, American Bar Association, 321 North Clark Street, Chicago, Illinois 60654-7598.

www.ababooks.org

ISBN 978-1-61438-055-9 (electronic)

To Rob Pearigen, Glenn Reynolds, Bob Lloyd, Otis Stephens, and Boris Bittker, each of whom made it possible for me to write this book BPD

To Patricia Cain, who first guided me through this process, and to all of the folks who have contacted me for the same guidance MLM

To Alene, who watched it alland wondered, "Why?" JML

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Becoming a Law Professor began as an office conversation between Denning and McCormick. We were soon joined by Lipshaw, who had been thinking about a similar project after the runaway success of his article How Not to Retire and Teach. The three of us have had a lot of fun writing this book, and hope that it will prove as useful to present and future candidates as it was enjoyable to write.

This book would not have been possible without the contribution and support of a number of people who thought that a book like this would be useful and who encouraged us to write it. In June of 2007, Denning guest-blogged at Concurring Opinions and mentioned that he was working on the book. A number of people gave thoughtful responses to his bleg* asking what ought to be included in the book. Not all the suggestions were signed, but we want to thank everyone who responded, including Bruce Boyden, Andy Grewal, James Grimmelman, David Hardy, Orin Kerr, Sarah Lawsky, and Robert Rhee.

Special thanks are owed to Ben Barton, Beth Burch, Miriam Cherry, Chad Flanders, Orly Lobel, Dan Markel, Bill Ross, Christina Sautter, Larry Solum, Brad Wendel, Chuck Young, and the anonymous reviewers at the ABA, each of whom read early drafts in their entirety and made extremely helpful suggestions for improving the final draft. Thanks, too, to Stephen Gidiere for putting us in touch with the right folks at ABA Publishing and to Rick Paszkiet for persuading his colleagues that a market existed for such a book.

The authors also thank Monica Nelson, Elizabeth Barclay, and Charlie Nelson, each of whom provided valuable research assistance on the book, including compiling and updating the bibliographic essay in Appendix A. Pam Davis and Donna Klosowsky were invaluable in preparing the manuscript.

Denning wishes to thank Dean John Carroll and the Cumberland School of Law for successive summer research grants that aided in the completion of this book. As always, he is humbled by and grateful for the constant love and support from Alli, Gram, and Meg.

McCormick wishes to thank the faculty at Chicago-Kent for helping to launch this part of her career during her time there as a VAP, particularly Marty Malin, Mary Rose Strubbe, and Katharine Baker. For the endless conversations about this topic, thanks to fellow VAPs Kari Aamot, Mark Bauer, Mike Cahill, Molly Current, Beth Henning, Joe Morrissey, Kristen Osenga, Mike Pardo, Greg Pingree, and Alex Tsesis, and non-VAPs Deb Cohen and Paul Secunda. Thanks to Dean John Carroll and the faculty at Cumberland School of Law for allowing her to see the other side of hiring. And finally, thanks to John, Morgan, Ceridwen, Rhiannon, Mark, Marla, Victoria, and everyone from Book Club, none of whom have ever doubted, even when she has.

Lipshaw wishes to thank Andy Klein and Brad Wendel for suggesting that the twenty humorous dos and don'ts ought to be an essay about not retiring and teaching, and Brannon and Marcia for including him in this project.

Brannon P. Denning

Birmingham, Alabama

Marcia L. McCormick

St. Louis, Missouri

Jeffrey M. Lipshaw

Boston, Massachusetts

FOREWORD

The New Realities of the Legal Academy

Lawrence B. Solum

Brannon P. Denning, Marcia L. McCormick, and Jeffrey M. Lipshaw have done the legal academy a great service by writing Becoming a Law Professor: A Candidate's Guide. This is a soup-to-nuts guide, taking aspiring legal academics from their first aspirations on a step-by-step journey through the practicalities of the Association of American Law School's hiring conference, on-campus interviews, and preparing for the first semester of teaching. Although the blogosphere is filled with advice and many helpful articles have been written about the process of becoming a law professor, there is nothing comparable to Becoming a Law Professorwhich is sure to become essential reading for anyone seeking a job as a legal academic.

One of the great virtues of Denning, McCormick, and Lipshaw's guide is that it reflects the changing nature and new realities of the legal academy. Not so many years ago, entry into the elite legal academy was mostly a function of two thingscredentials and connections. The ideal candidate graduated near the top of the class at a top-five law school, held an important editorial position on law review, clerked for a Supreme Court Justice, and practiced for a few years at an elite firm or government agency in New York or Washington. Credentials like these almost guaranteed a job at a very respectable law school, but the very best jobs went to those with connectionsthe few who were held in high esteem by the elite network of very successful legal academics and their friends in the bar and on the bench. The not-so-elite legal academy operated by a similar set of rules. Regional law schools were populated by a mix of graduates from elite schools and the top graduates of local schools, clerks of respected local judges, and alumni of elite law firms in the neighborhood. In what we now call the, bad old days, it was very difficult indeed for someone to become a law professor without glowing credentials and the right connections.