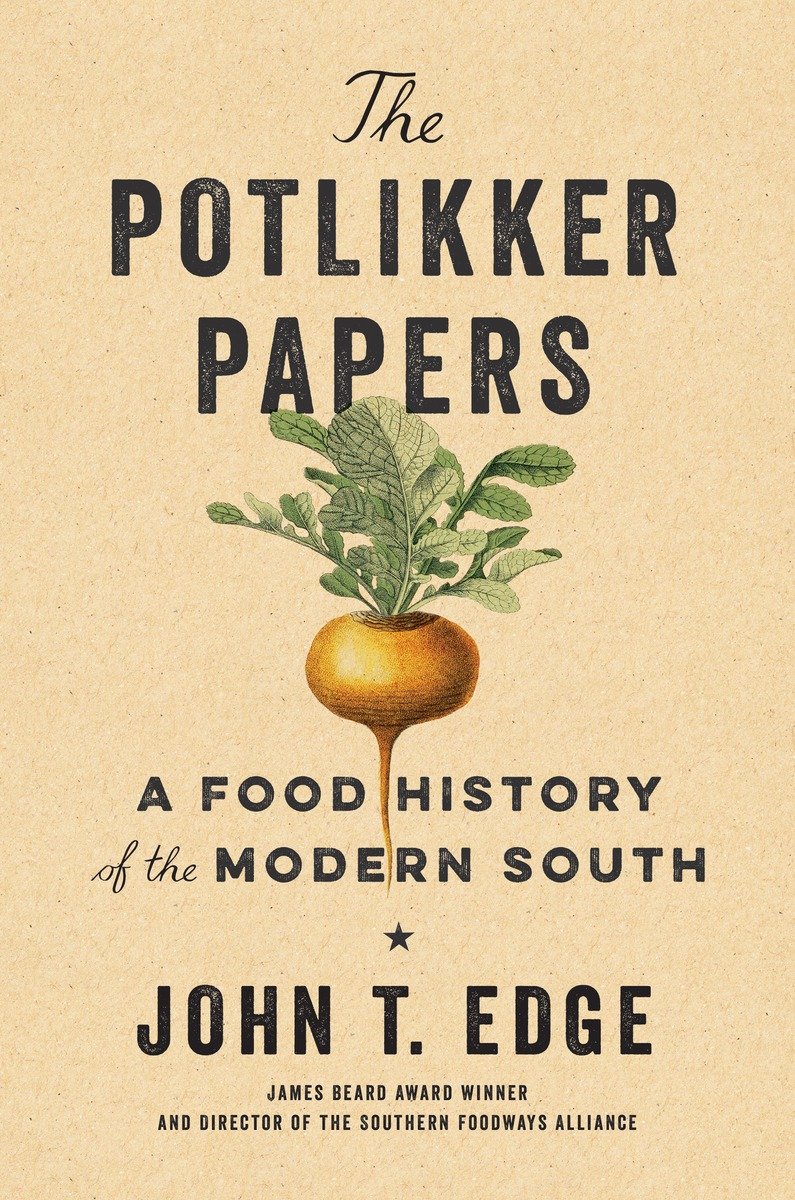

I learned much of what I know while studying at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi, and, later, directing the Southern Foodways Alliance at that same university. Research and writing for magazines and newspapers including Oxford American, Garden & Gun, TheNew York Times, Departures, Parade, and Gourmet informed the work that follows. I wrote most of The Potlikker Papers at Rivendell Writers Colony, high on the mountain in Sewanee, Tennessee, and in my backyard toolshed in Oxford, Mississippi.

F OREWORD (TO) J OHN E GERTON

I learned to explore my native region while borrowing from John Egerton, the Nashville journalist and social historian. Over a half-century career, Egerton sketched a democratic portrait of the American South and its peoples. His books were laments on race and class. They were catalogues of regional distinctiveness and documents of its presumed demise. They were rousts of the demons that lurked in this briar patch. They were jousts plotted to dislodge the wealthy and powerful from their perches.

Reading his words, I learned that writing about food didnt have to be an exercise in indulgence. Following his lead, I took tentative steps toward paying down the debts of pleasure and sustenance owed to our forebears. I had company. Borrowing from Egerton, two generations of thinkers and writers and cooks gained moral clarity and recognized common purpose. Buoyed by his leadership, the South rose to prominence as a culinary citadel.

A love of the region and a belief in the possibilities of the common table drove his queries. Time and again, Egerton asked how Southerners could reconcile a history of gross injustice with a deserved reputation for great food and warm hospitality. Egerton wondered how a culture rife with bigotry could produce hickory-smoked whole hog barbecue, parchment-crust fried okra, and downy spoonbread souffls. He begged answers to why blacks and women, long subjects of grievous mistreatment, had done most of the heavy lifting but received niggling credit.

Egerton offered no palliative answers. Instead, he adopted what he called the unwritten law of compensation, simplistically overstated, in which bad places make good books, good music, good art, and good food. The more messed-up a place is, the more inventive and freewheeling its creative voices, he said. Richly varied forms of artistic expression seem to burst forth from violent or repressive or otherwise dysfunctional societies.

As his career progressed, Egerton recognized that the South might realize its potential on farms and in kitchens. He believed that time at table offered reconciling possibilities. But before all could claim seats and revel in country ham and buttermilk biscuits and hope, he said more work needed to be done.

Not infrequently, Southern food now unlocks the rusty gates of race and class, age and sex, Egerton wrote in his 1987 book, Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History. On such occasions, a place at the table is like a ringside seat at the historical and ongoing drama of life in the region.

I conceived this book as a sequel to that one. And I imagined that John Egerton would write this foreword. When he died unexpectedly in the fall of 2013, I lost more than a friend and mentor. I lost my foreword writer. Thanks, John, for the place at the table. Ive tried hard not to squander your generous gifts.

C ONTENTS

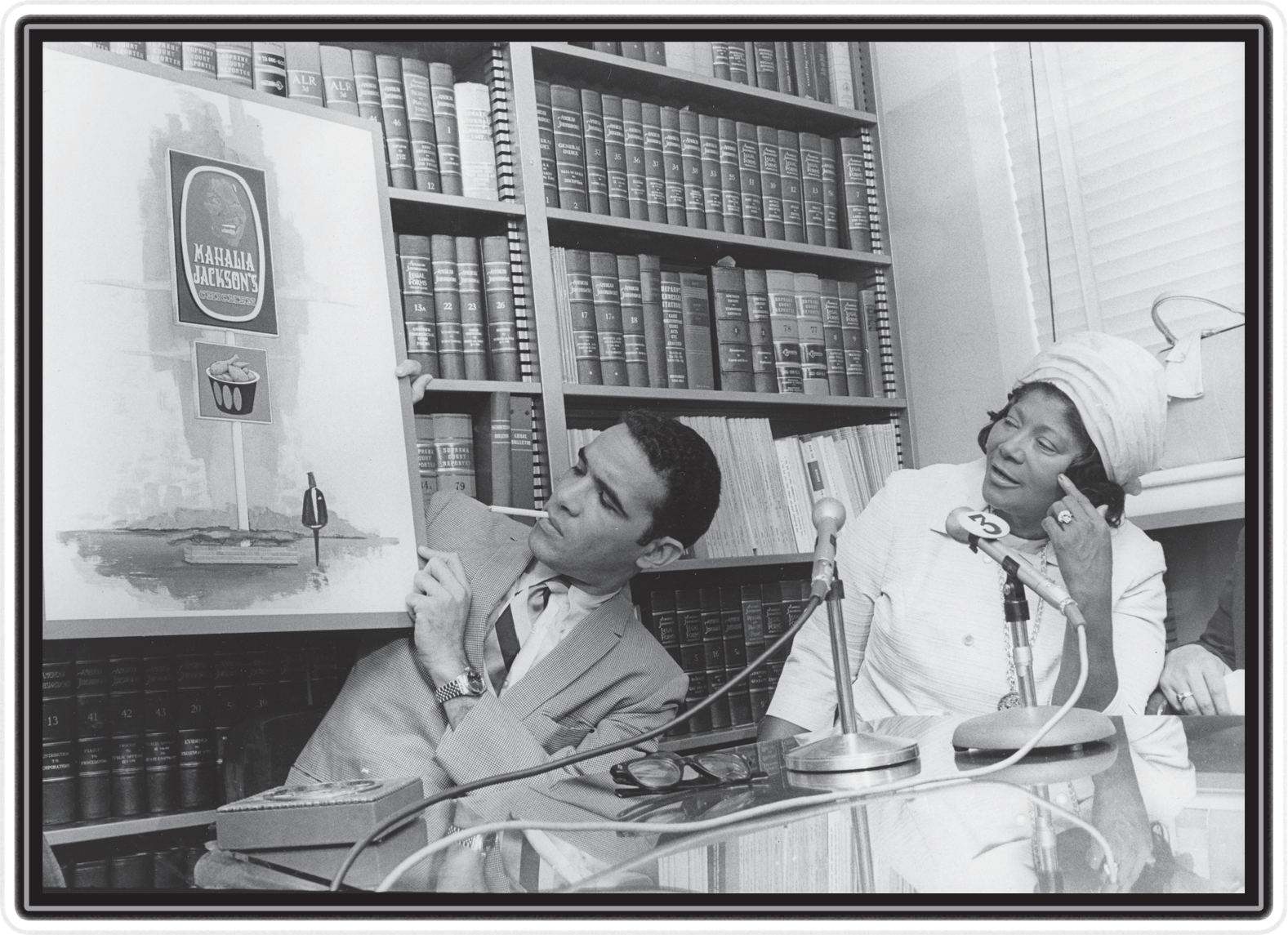

In the 1970s, black Southerners on a path to economic independence developed fast-food businesses. Here, Mahalia Jackson and Russell Sugarmon reviewed plans for the Memphis opening of Mahalia Jacksons Fried Chicken.

Potlikker: An Introduction

T he collards at Berthas Kitchen in North Charleston, South Carolina, are back-of-the-stove paragons. Simmered in a pigtail- and neckbone-perfumed potlikker, those greens showcase the talents of the black women who stir Berthas pots and the vitality of the crops that thrive in the Lowcountry loam. At the time of my visit in 2012, Joseph Fields, whose family has farmed nearby Johns Island for three generations, grew the greens for Berthas and a dozen other Charleston area restaurants. After a lunch of fried pork chops, red rice, and collards, I walked the crop rows with Fields, regarding his harvest to come.

We spoke of how global warming has transformed harvest patterns. We talked of the declining ranks of black farmers and the increasing number of white consumers who valorize their labor. We puzzled through why crackling cornbread, buckshot with pork skin shards, disappeared from cafs at about the time fried pig ears became salad garnishes in fine dining restaurants. As Fields rounded a turnrow, I asked how his family came to farm this land.

Gesturing toward an unseen house in the distance, Fields told me that his grandmother, Molly Johnson, earned the dollars to buy the family farm by wet-nursing the white baby of a nearby plantation owner. By bringing a white mouth to her black breast, Fields told me that his forebear nourished two families, one white and one black. He told me this without malice. His eyes didnt blink. His voice didnt climb a register. He simply shared a truth about his family and the South. In the telling, Joseph Fields made explicit the kind of complicated narratives that are deeply embedded in our food culture.

Eating is an agricultural act, Kentucky native Wendell Berry once wrote. In the South, that equation has been fraught, for in addition to being virtuous work in which writers like Berry take justifiable pride, agriculture begat the regions original sin: slavery. During the antebellum era, demand for enslaved labor to plant and harvest the fecund South drove a national dependence on cheap farmworkers. After the Civil War, white efforts to retain and later disinherit that labor have limited the horizons of black and white Southerners alike.