This book would not have been possible without the financial support of various funding bodies and institutions. Specifically, I would like to thank the Economic and Social Research Council for funding one of the studies this book is based on (RES-000-22-1294). I wish to thank the Grabowski Memorial Fund, Polish Aid Foundation Trust, and Mr Erazm Pruszyski for their assistance in completing the task of writing this book. I am also very grateful for the support generously provided by the Southlands Metho d ists Trust at University of Roehampton. I want to thank my co l leagues at the Department of Social Sciences at University of Ro e hampton who supported me throughout these years, in particular Dr Stephen Driver, Dr Michele Lamb, and Prof. Steven Groarke. Prof. John Eade from the same department has been far more than a colleague throughout these years , and his friendship was crucial for my own development. Thank you, John.

The assistance, advice, and patience from the i bidem - Verlag editor s , Max Jakob Horstmann and Valerie Lange also deserve my grat i tude.

I wish to also thank my wife, Katarzyna Depta-Garapich, who endured with great resolve and understanding the sometimes annoying fact of having an anthropologist as a husband.

Last but not the least, I want to thank the hundreds of migrants I spoke to for their time and patience.

Dr Micha P. Garapich

Preface

In the early morning of the 6th of June 2003 , a long queue began to form in front of the Polish Embassy on Great Portland Street in central London. In the course of the day, this queue grew larger and larger forcing people to wait up to three hours to be let into the building. In total, that day and the following 7th of June, nea r ly 7,000 Polish citizens turned up. These people, from various generations and cohorts of Poles who made London their home, came to central London to decide on one of the most important historical turning points their country was about to make. They were casting their votes in a referendum over the accession of Poland into the European Union (EU). In many ways, the result of that small-scale ballot among Poles living in London at that time was predictablearound 90% voted yes . In Poland, over 77 % of the voters endorsed entry into the EU.

The clear enthusiasm, which the London-based Poles showed over the future of Poland in Europe, was a sign of things to come. The then Labour governments decision made in early 2003 to open the British labour market to Polish nationals was well known and widely discussed among Polesboth in Poland and in their various communities abroad. In fact, during the pro p aganda war before the referendum, the right to freedom of movement and employment was presented by the Polish E U -enthusiasts as the biggest benefit for Polish citizens from joining the EU. For Poles living in London, many of whom were working in breach of the immigration law, overstaying their visas or sim p ly working in grey economy, it was a matter of deciding over their future as residents of the UK, it was an affirmation of their right to live, work, and settle in the UK. For many of these migrants, tur n ing out to cast a vote was a political act that would enable them to regulari s e their immigration status. If anyone is looking for an example of how individuals in their modest way shape the grand schemes of international politics, one need s to look no further. Many Poles casting the vote that day voted themselves in th er e by legitim isi ng flows and subsequent settlement into the UK.

The clear enthusiasm, which the London-based Poles showed over the future of Poland in Europe, was a sign of things to come. The then Labour governments decision made in early 2003 to open the British labour market to Polish nationals was well known and widely discussed among Polesboth in Poland and in their various communities abroad. In fact, during the pro p aganda war before the referendum, the right to freedom of movement and employment was presented by the Polish E U -enthusiasts as the biggest benefit for Polish citizens from joining the EU. For Poles living in London, many of whom were working in breach of the immigration law, overstaying their visas or sim p ly working in grey economy, it was a matter of deciding over their future as residents of the UK, it was an affirmation of their right to live, work, and settle in the UK. For many of these migrants, tur n ing out to cast a vote was a political act that would enable them to regulari s e their immigration status. If anyone is looking for an example of how individuals in their modest way shape the grand schemes of international politics, one need s to look no further. Many Poles casting the vote that day voted themselves in th er e by legitim isi ng flows and subsequent settlement into the UK.

As we now know , the results of the referendum came to have profound consequences for Europe, but especially for Bri t ain , triggering a massive migration wave and changing its d e mographics, neighbourhoods, and debates about immigration, society, the economy, and Britains place in Europe. It has pr e pared the ground for what the British press has called the biggest migration wave since the arrival of the French Huguenots in the late 17th century. Almost exactly a decade later, the British n a tional census showed that the number of Poles ha s increased te n fold ever since from a little above 50,000 to over half a million. However, the sensationalist headlines, so cherished by the media, mask some deeper layers of meanings and unanswered questions. Who are we exactly talking about? Who are these Poles who, among other Eastern and Central Europeans , populate London and other towns and villages of the UK and , despite the economic downturn and recession of the last couple of years defy simplistic economic formulas , do not go back to Poland but remain in Bri t ain? Were these migrations so new or were they simply another chapter in a long history of transnational connections woven b e tween Poland and the UK for decades? And how do these people think, act, and negotiate their place, belonging, and life in an i n creasingly interconnected, interdependent world? How do they articulate their migration experience, their interaction with the British population, and what, in general, do they make of their new home? It is clear that these questions are ultimately questions about the future of Britain itself, since these people will become or already are friends, workmates, relatives, clients, costumers, neighbours, and passers-by in numerous British cities.

This book seeks to answer some of these questions from a classical anthropological perspective by looking from a bottom-up perspective of the everyday meaning-making of various social actors and look at what people do, why they do it, how they i n terpret the social world around them, and how their actions are embedded in the complex interplay between culture, economy, power, dominant narratives of the states, and ultimately, citize n ship in an increasingly fluid, interconnected world. As social a n thropologist ( as Clifford Geertz famously observed) , I see human beings as constructing and being constructed by webs of mea n ings, actions, and structures they have spun themselves and that relationship constituting social life. In that way, the 7,000 people who turned out to vote that June morning in 2003 in London could be regarded as a symbolic avant-garde of todays migrant population, a taste of things to come , and confirmation of the i n dividuals power. They established the foundations for the ma s sive influx of Polish migrants into Britain after Poland joined the EU in 2004. These foundations were not just created by the ec o nomic environment, labour market gaps, or migratory networks so crucial in assisting further flowsthey were also shaped by a particular migration culture into which Poles are sociali s ed, a sp e cific domain of notions, symbols, and narratives that refer to h u man mobility in Polish society. In a grande duree perspective, then, how Poles act, make meaning of , and position themselves in the new Europe, and especially in such a global city as London, rest to a large extent on their own cultural resources and traditions, which were marked by huge past migratory movements, beco m ing an essential part of their grand dominant narratives, as well as local stories of resilience, survival, and resistance in the face of historic turmoil, economic calamities, wars, or shifting geogr a phies of power in the post-Cold War world.

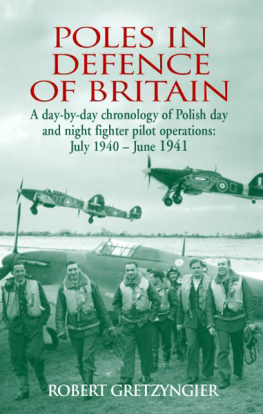

The main core of this books argument is that it is imposs i ble to understand Polish migration to the UK and, in particular, London, without digging deeper into these meaning-making pra c tices, which are also crucial for our understanding of particular features of Londons current multicultural politics. This isnt sim p ly to restate the banal that in order to understand the present we need to look at the past, but also how past is being reproduced, selectively revived, and embedded in social practice. To illustrate this, lets look at another small ethnographic detail in the life of Londons Poles: four years after that summer in 2003, many of those Poles who were queuing to cast their votes in the above-mentioned referendum were present at a special reception for the Polish community hosted by the Mayor of London, Ken Livin g stone. The reception was viewed widely as an attempt by the Mayor to secure votes from that ethnic group, for his reelection the year after. During the reception, a second-generation Polish community leader made a speech in which he highlighted the continuity of Polish presence in the UK dating from the Second World War. He spoke about the role of Polish pilots in the Battle for Britain and linked this to the role of Poles in contemporary multicultural Britain. As he said, Poles were a model for other ethnic minorities in terms of integration and successful peaceful cohabitation.

The clear enthusiasm, which the London-based Poles showed over the future of Poland in Europe, was a sign of things to come. The then Labour governments decision made in early 2003 to open the British labour market to Polish nationals was well known and widely discussed among Polesboth in Poland and in their various communities abroad. In fact, during the pro p aganda war before the referendum, the right to freedom of movement and employment was presented by the Polish E U -enthusiasts as the biggest benefit for Polish citizens from joining the EU. For Poles living in London, many of whom were working in breach of the immigration law, overstaying their visas or sim p ly working in grey economy, it was a matter of deciding over their future as residents of the UK, it was an affirmation of their right to live, work, and settle in the UK. For many of these migrants, tur n ing out to cast a vote was a political act that would enable them to regulari s e their immigration status. If anyone is looking for an example of how individuals in their modest way shape the grand schemes of international politics, one need s to look no further. Many Poles casting the vote that day voted themselves in th er e by legitim isi ng flows and subsequent settlement into the UK.

The clear enthusiasm, which the London-based Poles showed over the future of Poland in Europe, was a sign of things to come. The then Labour governments decision made in early 2003 to open the British labour market to Polish nationals was well known and widely discussed among Polesboth in Poland and in their various communities abroad. In fact, during the pro p aganda war before the referendum, the right to freedom of movement and employment was presented by the Polish E U -enthusiasts as the biggest benefit for Polish citizens from joining the EU. For Poles living in London, many of whom were working in breach of the immigration law, overstaying their visas or sim p ly working in grey economy, it was a matter of deciding over their future as residents of the UK, it was an affirmation of their right to live, work, and settle in the UK. For many of these migrants, tur n ing out to cast a vote was a political act that would enable them to regulari s e their immigration status. If anyone is looking for an example of how individuals in their modest way shape the grand schemes of international politics, one need s to look no further. Many Poles casting the vote that day voted themselves in th er e by legitim isi ng flows and subsequent settlement into the UK.