Copyright 2017 by Meredith Hindley

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

PublicAffairs

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.publicaffairsbooks.com

@Public_Affairs

First Edition: October 2017

Published by PublicAffairs, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Hindley, Meredith, author.

Title: Destination Casablanca : exile, espionage, and the battle for North Africa in World War II / Meredith Hindley.

Other titles: Exile, espionage, and the battle for North Africa in World War II

Description: New York : PublicAffairs, [2017] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017018911 | ISBN 9781610394055 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781610394062 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: World War, 19391945CampaignsMorocco. | World War, 19391945MoroccoCasablanca. | World War, 19391945Intelligence service. | FranceForeign relationsUnited States. | United StatesForeign relationsFrance.

Classification: LCC D766.99.M6 H56 2017 | DDC 940.54/234dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017018911

E3-20171229-JV-PC

For my parents, Virginia and Richard, who instilled in me an affection for books and history.

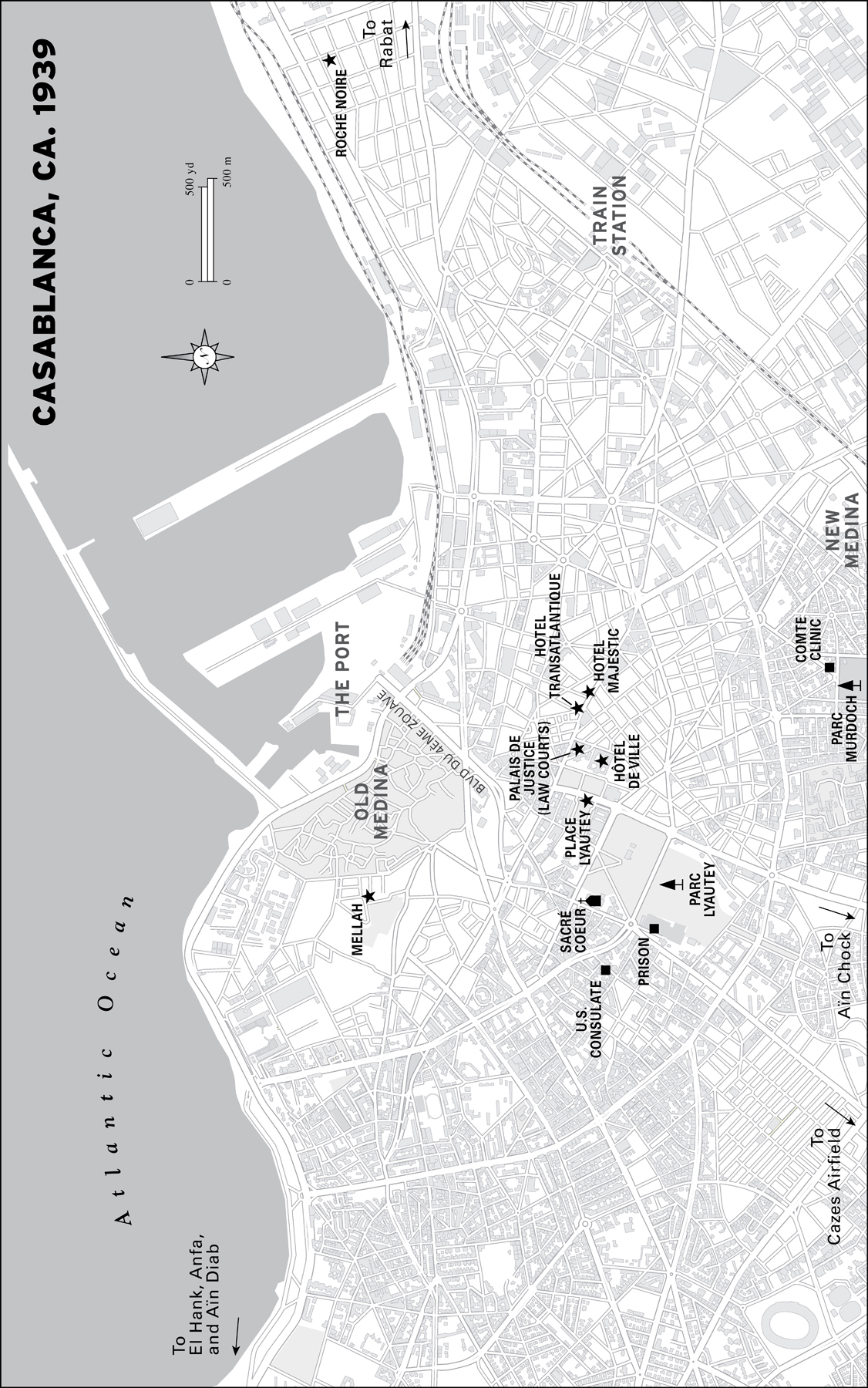

A NTOINE DE S AINT -E XUPRY, A TWENTY-NINE-YEAR-OLD PILOT FOR Aropostale, soared above the terra-cotta Moroccan desert on the edge of Casablanca. As the white city came into focus, he could make out the vast grey-blue reaches of the Atlantic Ocean to the west. Hed regularly been making the run between Casablanca and Dakar in the cockpit of a Latcore 28, being one of the few pilots braveor foolishenough to fly the mail routes between Frances African colonies. Hed cheated death at least once too, surviving a crash in the desert. There would be more of those.

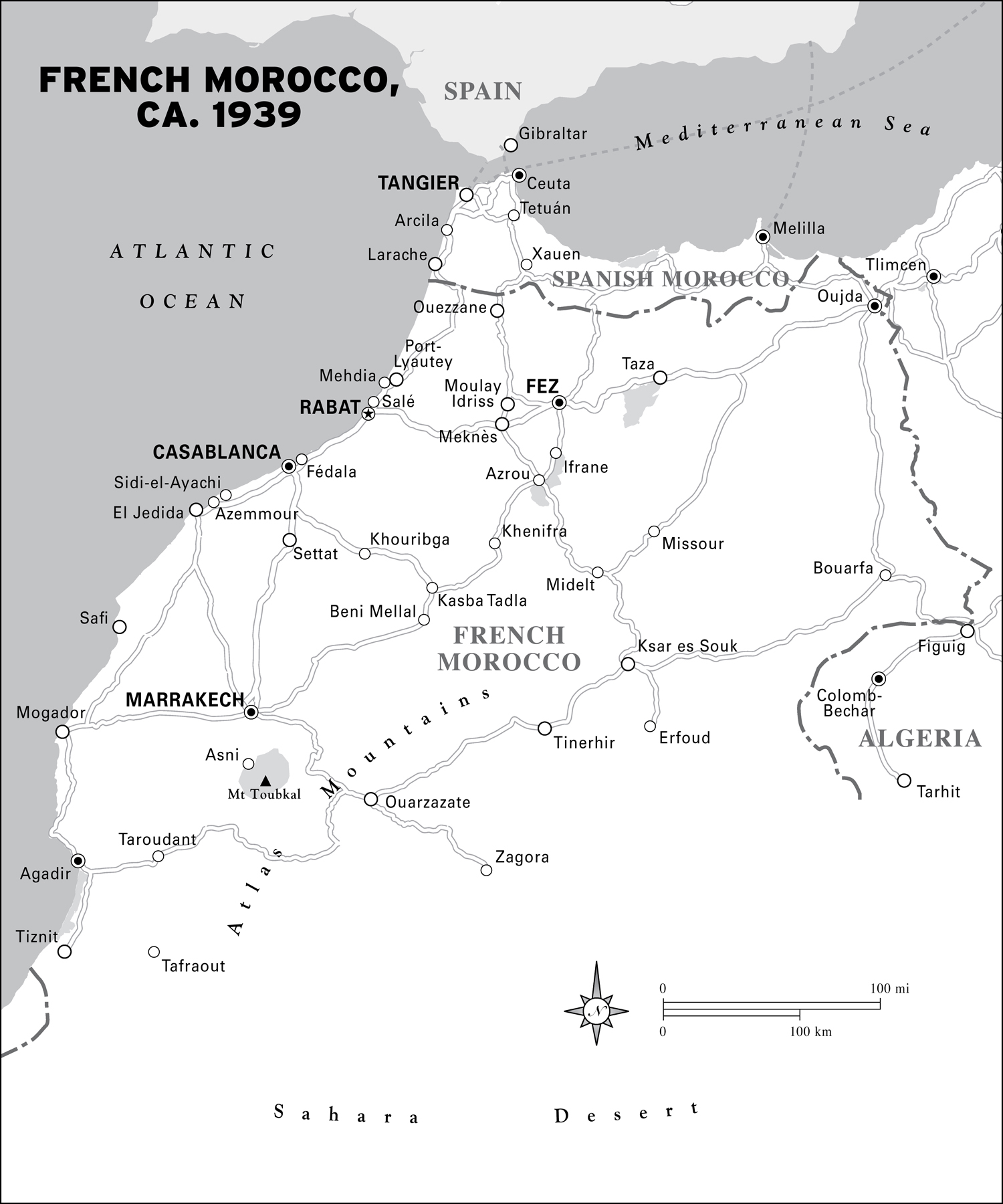

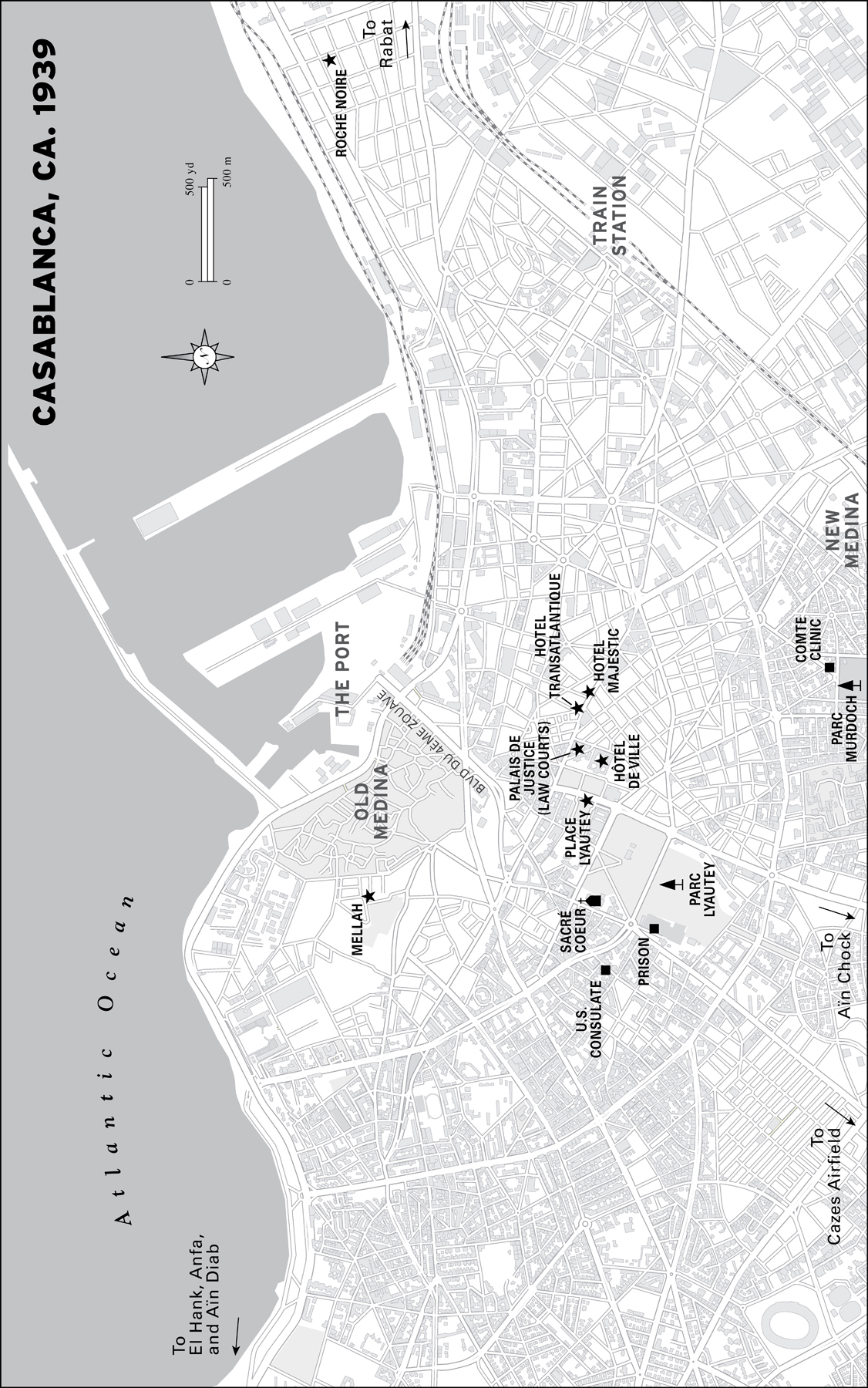

Saint-Exuprys career as a pilot began to take shape some eight years earlier in Casablanca in 1921, where he trained with the nascent French air force. He earned his wings while stationed with the 37th Flight Group at Cazes airfield, located a few miles outside the city. Hed tried his hand as a naval officer and an architect, but neither suited him. In an airplane, however, Saint-Exupry found his mtier. A lumbering man who seemed perpetually out of place, he felt at home in the sky. In Casablanca he learned to fly with a compass, which became his touchstone on the long desert flights that forged his reputation.

After a disappointing sojourn in France, hed returned to Casablanca in the late 1920s. The bustling port citys thirst for mail from France and elsewhere kept him in the air, but on the ground the streets of the white city offered an array of cafs in which to drink coffee and jot down his latest story between flights. He also spent time running Aropostales station at Cape Juby in southern Morocco, where he made sure his fellow pilots arrived and departed in one piece. If one failed to arrive on time, it was his job to search between Casablanca and Cape Juby for the lost man and mail. I ready myself for great adventure with a certain vanity, he wrote of preparing for a search, but then a far-away hum announces that the plane will come in, announces that life is altogether more simple than I had thought, that romanticism has its limits, and that the lovely persona in which I have dressed myself is somewhat ridiculous. Saint-Exupry turned his aerial exploits in French Morocco and beyond into fodder for his first novel, Southern Mail, published in 1929.

He was a colon, or settler, the name given to the French and other Europeans who descended on Morocco in the early twentieth century. He was also a Christian and a member of the recently installed ruling class in a land long ruled by Muslims. His triumphant language simplifies, in many ways, Moroccos descent into colonialism. France came to Morocco not to convert the masses, although some missionaries would try, but to exploit its resources. The French crusaded not for Christianity but for colonialism and capitalism.

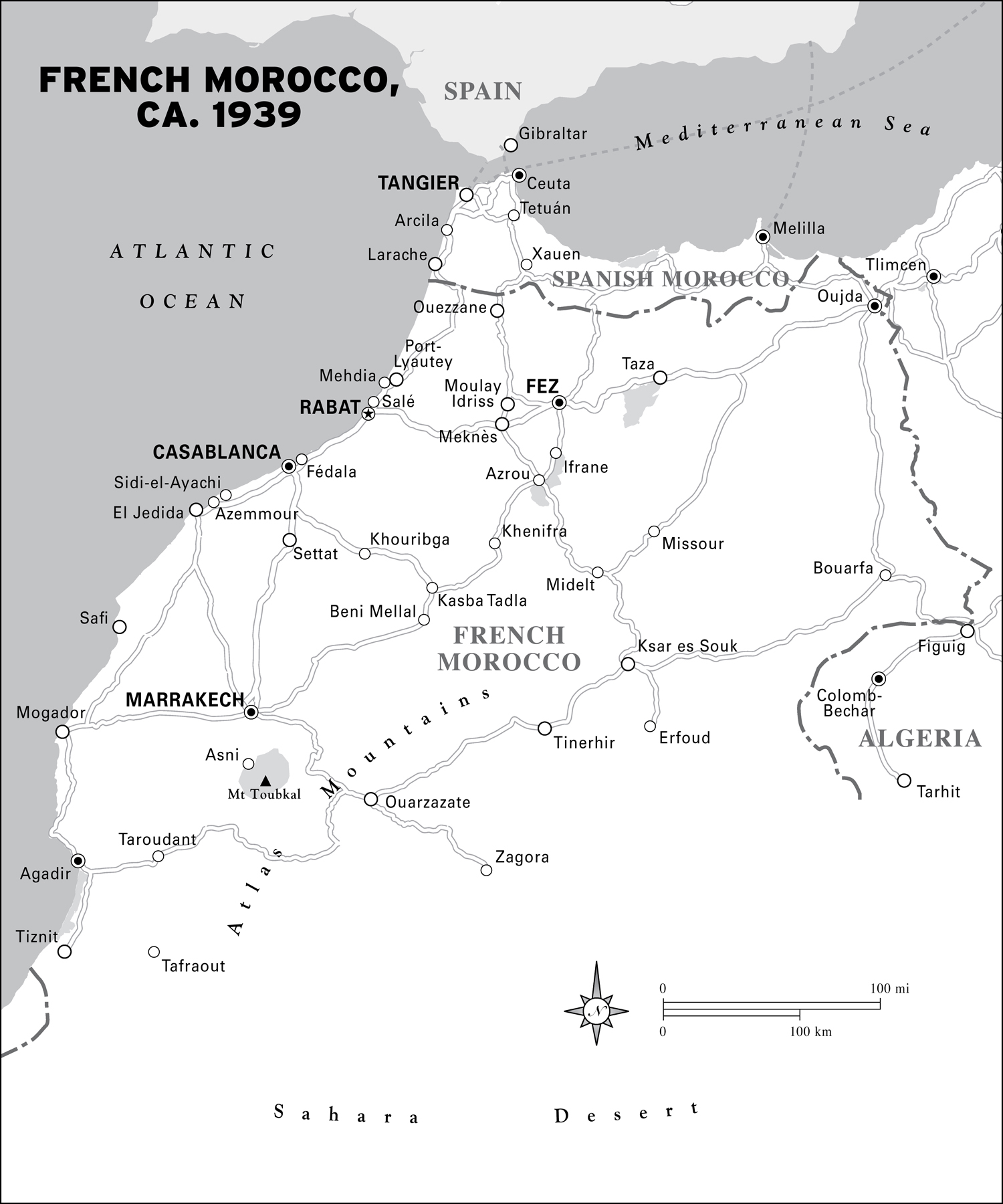

For centuries, the Alaouite dynasty had kept the Europeans at bay, even as foreign powers colonized the rest of the African continent. It was an impressive feat, given Moroccos prime location on the Atlantic coast of Africa. After an assertive push by Germany, France, and Spain at the beginning of the twentieth century, abetted by internal strife, the Europeans carved Morocco up for their own ends. Under the Treaty of Fez, signed in 1912, Spain received the northern quarter of Morocco, the city of Tangier became an international zone, and France took the southern three-quarters of Morocco, including Casablanca. With the establishment of the French Protectorate of Morocco, France now controlled a block of colonies in North Africa stretching from Morocco through Algeria to Tunisia.

French Moroccos first resident-general, Hubert Lyautey, was a skilled colonial administrator and fierce soldier with the heart of a romantic. Bookish by nature, he studied and absorbed Arab customs and language, developing a deep respect for Islam. Even as France imposed its will on Morocco, Lyautey did not want to see Moroccan culture erased. Lyautey pioneered the idea of the protectorate, a style of government under which the colony retained its traditional cultural and political institutions rather than being assimilated.

Under the French Protectorate of Morocco, the sultan continued to rule the country with guidance from Francemeaning, of course, that France ran Moroccos economy, directed its finances, oversaw its defense, and represented its interests abroad. As a representative and descendent of Mohammed, the sultan remained in charge of his Muslim subjects spiritual lives.

Instead of displacing the powerful families that had ruled Morocco for centuries, Lyautey cultivated their support. The pashas and their families possessed a connection with the Moroccan people and methods of maintaining control over the populace that the French could never achieve with either laws or soldiers.

To bring French Morocco into the twentieth century, Lyautey launched a massive modernization project that transformed the country and Casablanca. He lured some of the brightest minds in architecture, social planning, education, and military affairs to the country to build cities, roads, schools, power plants, ports, and railroads. Modern agricultural techniques also bolstered Moroccos food supply.