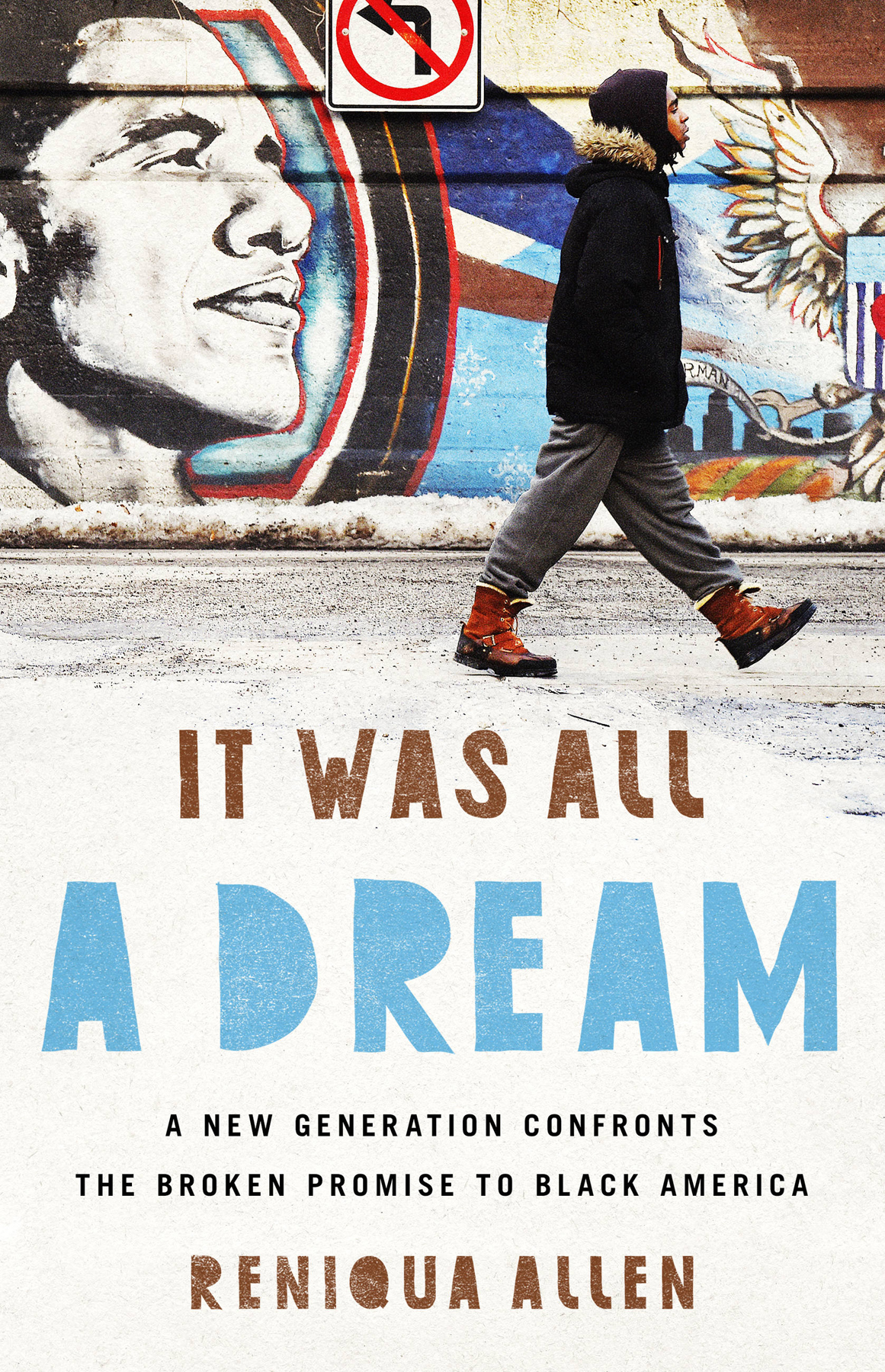

Copyright 2019 by Reniqua Allen

Jacket design by Pete Garceau

Jacket photograph The Washington Post/Getty Images

Cover copyright 2019 Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright.

The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com.

Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Nation Books

116 East 16th Street, 8th Floor New York, NY 10003

www.nationbooks.org

@NationBooks

First Edition: January 2019

Published by Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of

Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Nation Books is a co-publishing venture of the Nation Institute and the Perseus Books.

To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Allen, Reniqua, author.

Title: It was all a dream : a new generation confronts the broken promise to Black America / Reniqua Allen.

Description: New York, NY : Nation Books, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018028528| ISBN 9781568585864 (hardcover) | ISBN 9781568585871 (e-book)

Subjects: LCSH: African AmericansEconomic conditions21st century. | Race discriminationEconomic aspectsUnited States.

Classification: LCC E185.8 .A56 2019 | DDC 330.900896/073dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018028528

E3-20181120-JV-NF-ORI

For my Aunt Dee

my American Dream

It was all a dream

I used to read Word Up! magazine

SaltNPepa and Heavy D up in the limousine

Hangin pictures on my wall

Every Saturday Rap Attack, Mr. Magic, Marley Marl

I let my tape rock til my tape pop

Smokin weed and bamboo, sippin on private stock

Way back, when I had the red and black lumberjack

With the hat to match

T HE N OTORIOUS B.I.G, J UICY

M Y FIRST VERSION OF THE A MERICAN D REAM WAS SIMPLE, MATERIALISTIC, AND perhaps misguided from the jump. I remember it clearly, its conception around the time puberty was beginning to take hold of my body and I was captivated by all things adult. I would have a hot red Toyota Corolla, a perfect chocolate-brown husband with shimmering skin who looked like Blair Underwood, and darling Brown kids. Id be some sort of professional, with a graduate degree and a well-paying corporate job, and Id live in a fancy New York City condo. Oh, and Id of course have a slick hourglass shape, flat stomach, and long straight hair with my edges laid.

It completely grosses me out looking back, but I understand now that it was the beginning of my quest to succeed and move up in class and social status. Back then, in the eighties and nineties, the world seemed to hold endless possibilities. People constantly told me that I could be anything I wanted to be, and I had no reason not to believe them. My own family had moved on up from the South to New York during the second wave of the Great Migration, and then fled the concrete jungle to the suburbs, claiming their own piece of the Dream. My mother, a baby boomer who came of age of during the Civil Rights era, had completed undergraduate and graduate school and owned her own home. Plus, there were a ton of Black middle-class shows on television, Oprah Winfrey was shattering all kinds of glass ceilings in the real world, and the words of Biggies dreams realized lulled me to sleep every night. Sure, I was aware of the shitty sides of America: I gasped when riots broke in Los Angeles, cried when Phillip Pannell, a young Black man, was killed by cops in my own hood, and watched in horror as Anita Hill was attacked for speaking out against sexual harassment. But it seemed for a while that my generation of Black millennials would actually do better than our parents and prove that for Black Americans, dreams could come true. Looking back, I think perhaps I was just being young and nave, having not fully understood what America often does to young Black kids with dreams of a better life.

As the world changed and I grew up, my dream evolved. It was no longer solely about material things; I wanted to make some kind of difference in the world, too.her friends, and had a fine man at the end of the series. Plus, her real life portrayer, Dana Owens, better known as Queen Latifah, was from Jerseyjust like me.

Today I laugh at my 1980s and 1990s notion of making it, yet at its core it never really changed. My American Dream was to not fuck up. My dream was to defy expectations. To be unpredictable, to do something better and something more than my ancestors. Perhaps I thought that if these dreams came true, I would finally be respected, embraced, so that America would recognize that I too existed and had a voice. In retrospect, I wonder why I even cared about any of that, because again and again America has shown it cares so little about people who look like me.

A S A MERICANS WE LOVE TO OBSESS ABOUT THE SO-CALLED A MERICAN Dream. We fight over whether its attainable, whether its dying, or whom its even for, though we rarely talk about what it is or admit that we all have our different versions of it. The American Dream is one of the most enduring myths in America, yet it is also one of its most prominent falsehoods. The Dream, the idea that anyone can succeed and enjoy a prosperous life through hard work, has been around since the founding of the country. But despite the reality that the Dream applies only to a limited number of people, America never seems to grow weary of this idea. The Puritans and Pilgrims believed that they could build a kind of utopia in the new world; Benjamin Franklin and Abraham Lincoln rose from humble beginnings to shape our nation; and Horatio Alger popularized the rags-to-riches narrative for generations of young men.

The term itself was first coined by James Truslow Adams in 1931 during the Great Depression. He defined the American Dream as a dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability or achievement. Though he left the idea ambiguous, he was careful to clarify what it was not. It was not about community or material possessions, but

A 2017 survey by the Pew Research Center shows that if anything, the popularity and belief in the American Dream is growing, not shrinking46 percent of Americans believe they are on their way to achieving it, and 36 percent think they have already achieved it. The reality is different. Wealth inequality is at a historically high level, wages have stagnated despite increases in productivity, and it is harder than ever for Americans at any level to move above the social strata they were born into. Yet millennials too fall into that same thinking. The same survey found that 61 percent of millennials think theyre on their way to achieving the American Dream, though only 29 percent say their family has achieved it. And only 9 percent believe that the Dream is out of reach.