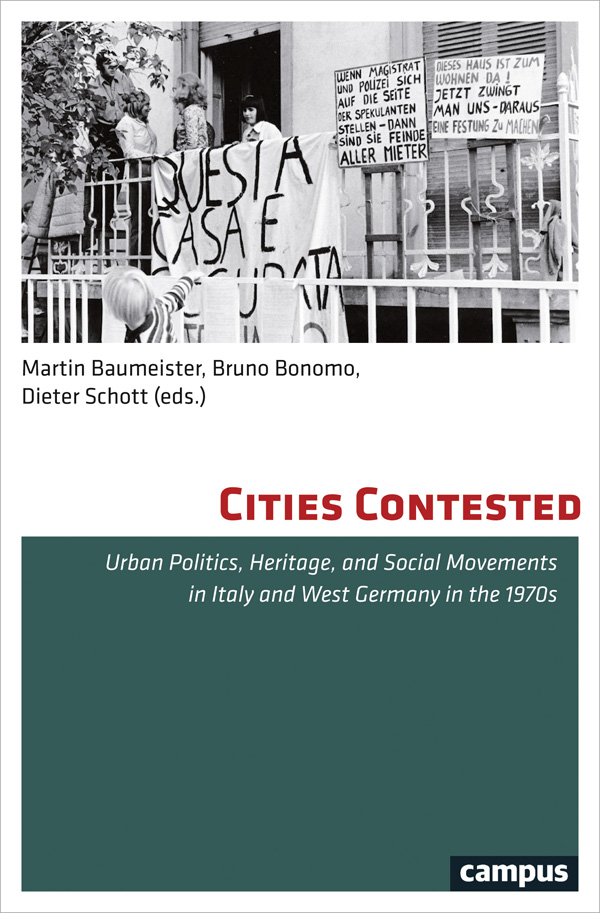

Save Our Cities Now! The Perception of Urban Crisis in the Early 1970s

In May 1971, the Deutscher Stdtetag , the Association of German Cities, held its convention in Munich. Hans-Jochen Vogel, president of the Association, mayor of the Bavarian capital and a prominent Social Democratic politician, gave the keynote lecture under the title of the conventions programmatic motto: Save our cities now! In his speech, Vogel drew a pitch-black picture of the situation of West German cities which, according to his diagnosis, were threatened by a deep crisis after the enormous effort and impressive successes of 25 years of postwar reconstruction. He saw obvious parallels to the United States, quoting President Nixon who had recently declared that one would need another American revolution in order to save the countrys cities from the brink of a precipice. Munichs mayor listed a whole series of symptoms characterizing the difficult situation of the growing cities and urban agglomerations: among others, the decay of older residential areas and historic city centers, urban sprawl and the mushrooming of new faceless districts, traffic congestion and heavy pollution, an increasingly insufficient infrastructure in education and the public health system, growing social inequality and disintegration. Vogel diagnosed a deep urban crisis of epochal dimensions, which, for its part, was a manifestation of profound transformations in all spheres of life. He declared that the future of the cities would be decided not in the sphere of urbanism and by urban experts, but in politics. For Vogel, a pragmatic reformer and certainly not a radical intellectual, the roots of the problems were to be found in the development of capitalism, especially in exploding real estate prices and the disparity between strong private financial power and weak municipal finances.

Vogels statement as well as the Stdtetag meeting had a considerable media impact at its time. The influential magazine Der Spiegel made it its cover story, transforming the Stdtetags strong appeal into the rather pessimistic question: Can we still save the cities?expressed a growing sense of unease about recent urban development and modern urban life. Summed up in the rather vague term of urban crisis, this sense of unease gained ground in manifold political and academic discourses of the postwar era, especially during the sixties and seventies.

Urban crisis referred to a variety of problems in rather different contexts. In the United States, it was marked by general societal struggles often perceived in categories of race and class, while in Western Europe it was influenced, apart from wider political and social contexts, by normative concepts and ideas of distinctive European traditions of city and urbanity. And all of them expressed an urgent desire to remedy a supposedly menacing, dangerous situation affecting the cities and their respective societies by political means. These could consist either of pragmatic, piecemeal reform, repair measures as spelled out by Vogel oras the vociferous Left of the seventies hopedof a fundamental societal change, a revolution which was to take cities as its point of departure.

In Italy, symptoms of the urban crisis such as congestion, poor housing conditions, lack of municipal finances, inadequacy of services and increasing social tensions appeared ever more widespread and acute over the seventies., Italo Calvino masterfully expressed the theme in literary terms. In one of his most renowned books, originally published in 1972, the great writer drafted a series of archetypical imaginary cities out of an evaluation of the contemporary urban world as passionate as it was critical:

What is the city today, for us? I believe that I have written something like a last love poem addressed to the city, at a time when it is increasingly difficult to live there. It looks, indeed, as if we are approaching a period of crisis in urban life; and Invisible Cities is like a dream born out of the heart of the unlivable cities we know.

The 1970s as a Period of Structural Rupture

In the debates about urban crisis cities were often considered exemplary sites, as mirrors and hotspots of deep general transformations of Western societies, then still more felt or anticipated than fully grasped. The deep sense of crisis as perceived by contemporaries fits well with the way the seventies are addressed in current academic debates. Many historians hold that the seventies mark the opening of a profound longer-term crisis-ridden structural rupture, though views and opinions about the scope and character of this break differ. While Niall Ferguson considers the seventies more as the seedbed of future crises than as the crisis conjuncture itself when the shock of the global had only just begun, Charles Maier maintains that the West did experience a decade of crisis, comparable to the earlier period of twentieth-century economic hammering in the 1930s and to the geopolitical meltdown that preceded World War I: The turmoil of the 1970s provoked a fundamental rethinking of the economic and political axioms that had been taken for granted since the Second World War. It closed the postwar era and its policy premises. Unlike the two earlier turbulent eras, 19051914 and 19291939, the shake-up of the seventies did not lead to a major world conflict. The postwar reconstruction had definitively come to an end, the decades of growth and continuously rising prosperity were closed and the Keynesian consensus dominating the economic policies of Western European countries was quickly eroding.

With good reason, it has been argued recently that the historiographical debates on the seventies, dominated by British, French and German scholars, are for the most part anchored in specific national contexts and shaped by contemporary perceptions, political factors and historiographical traditions.