PENGUIN MODERN CLASSICS

THE ORIGINS OF TOTALITARIANISM

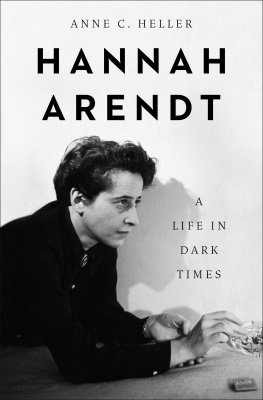

Hannah Arendt was born into a secular family of German Jews in Hanover in 1906. At university in Marburg, she was taught by the philosopher Martin Heidegger, with whom she developed a romantic relationship, complicated by his later affiliation with the Nazi party. She received her doctorate in philosophy from the University of Heidelberg and began researching antisemitism. In 1933, Arendt was arrested and briefly imprisoned by the Gestapo, after which she fled Germany for Paris, where she worked for the immigration of Jewish refugee children into Palestine. In 1937, she was stripped of her German citizenship. She married the Marxist philosopher Heinrich Blcher in 1940; the same year, she was detained in an internment camp in southwestern France as an enemy alien. After this, she left Europe for the United States, and became an American citizen ten years later.

During her time in the US, Arendt was a research director of the Conference on Jewish Relations, chief editor of Schocken Books, executive director of Jewish Cultural Reconstruction in New York City and a visiting professor at several universities, including Princeton, where she was the first female lecturer.

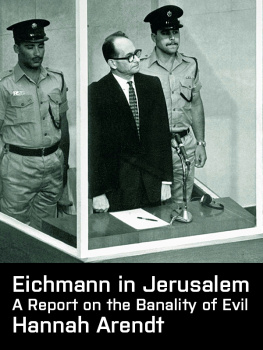

Hannah Arendts many books include The Origins of Totalitarianism (1951), The Human Condition (1958) and Eichmann in Jerusalem (1963), in which she coined the famous phrase the banality of evil. She died in December 1975.

Hannah Arendt

THE ORIGINS OF TOTALITARIANISM

PENGUIN CLASSICS

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Penguin Classics is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published in 1951

First published in Penguin Classics 2017

Copyright Hannah Arendt, 1966, 1968

Copyright renewed Hannah Arendt, 1948, 1951

Copyright renewed Hannah Arendt, 1976

Copyright renewed Mary McCarthy West, 1979

Copyright renewed Lotte Kohler, 1994

Cover illustration Photo12/UIG via Getty Images

ISBN: 978-0-241-31676-4

To Heinrich Blcher

Preface to the First Edition

Weder dem Vergangenen anheimfallen noch dem Zuknftigen. Es kommt darauf an, ganz gegenwrtig zu sein.

Karl Jaspers

Two world wars in one generation, separated by an uninterrupted chain of local wars and revolutions, followed by no peace treaty for the vanquished and no respite for the victor, have ended in the anticipation of a third World War between the two remaining world powers. This moment of anticipation is like the calm that settles after all hopes have died. We no longer hope for an eventual restoration of the old world order with all its traditions, or for the reintegration of the masses of five continents who have been thrown into a chaos produced by the violence of wars and revolutions and the growing decay of all that has still been spared. Under the most diverse conditions and disparate circumstances, we watch the development of the same phenomena homelessness on an unprecedented scale, rootlessness to an unprecedented depth.

Never has our future been more unpredictable, never have we depended so much on political forces that cannot be trusted to follow the rules of common sense and self-interest forces that look like sheer insanity, if judged by the standards of other centuries. It is as though mankind had divided itself between those who believe in human omnipotence (who think that everything is possible if one knows how to organize masses for it) and those for whom powerlessness has become the major experience of their lives.

On the level of historical insight and political thought there prevails an ill-defined, general agreement that the essential structure of all civilizations is at the breaking point. Although it may seem better preserved in some parts of the world than in others, it can nowhere provide the guidance to the possibilities of the century, or an adequate response to its horrors. Desperate hope and desperate fear often seem closer to the center of such events than balanced judgment and measured insight. The central events of our time are not less effectively forgotten by those committed to a belief in an unavoidable doom, than by those who have given themselves up to reckless optimism.

This book has been written against a background of both reckless optimism and reckless despair. It holds that Progress and Doom are two sides of the same medal; that both are articles of superstition, not of faith. It was written out of the conviction that it should be possible to discover the hidden mechanics by which all traditional elements of our political and spiritual world were dissolved into a conglomeration where everything seems to have lost specific value, and has become unrecognizable for human comprehension, unusable for human purpose. To yield to the mere process of disintegration has become an irresistible temptation, not only because it has assumed the spurious grandeur of historical necessity, but also because everything outside it has begun to appear lifeless, bloodless, meaningless, and unreal.

The conviction that everything that happens on earth must be comprehensible to man can lead to interpreting history by commonplaces. Comprehension does not mean denying the outrageous, deducing the unprecedented from precedents, or explaining phenomena by such analogies and generalities that the impact of reality and the shock of experience are no longer felt. It means, rather, examining and bearing consciously the burden which our century has placed on us neither denying its existence nor submitting meekly to its weight. Comprehension, in short, means the unpremeditated, attentive facing up to, and resisting of, reality whatever it may be.

In this sense, it must be possible to face and understand the outrageous fact that so small (and, in world politics, so unimportant) a phenomenon as the Jewish question and antisemitism could become the catalytic agent for first, the Nazi movement, then a world war, and finally the establishment of death factories. Or, the grotesque disparity between cause and effect which introduced the era of imperialism, when economic difficulties led, in a few decades, to a profound transformation of political conditions all over the world. Or, the curious contradiction between the totalitarian movements avowed cynical realism and their conspicuous disdain of the whole texture of reality. Or, the irritating incompatibility between the actual power of modern man (greater than ever before, great to the point where he might challenge the very existence of his own universe) and the impotence of modern men to live in, and understand the sense of, a world which their own strength has established.

The totalitarian attempt at global conquest and total domination has been the destructive way out of all impasses. Its victory may coincide with the destruction of humanity; wherever it has ruled, it has begun to destroy the essence of man. Yet to turn our backs on the destructive forces of the century is of little avail.

The trouble is that our period has so strangely intertwined the good with the bad that without the imperialists expansion for expansions sake, the world might never have become one; without the bourgeoisies political device of power for powers sake, the extent of human strength might never have been discovered; without the fictitious world of totalitarian movements, in which with unparalleled clarity the essential uncertainties of our time have been spelled out, we might have been driven to our doom without ever becoming aware of what has been happening.