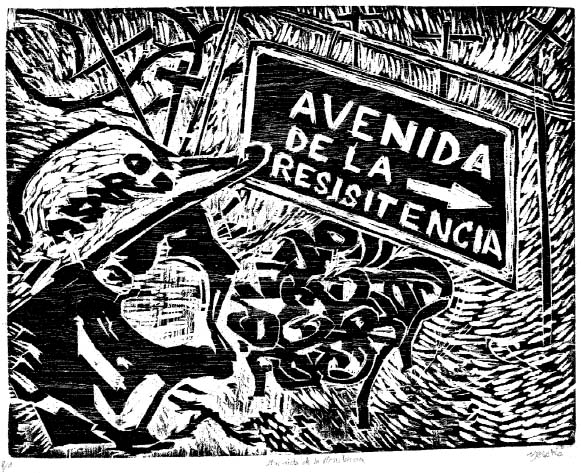

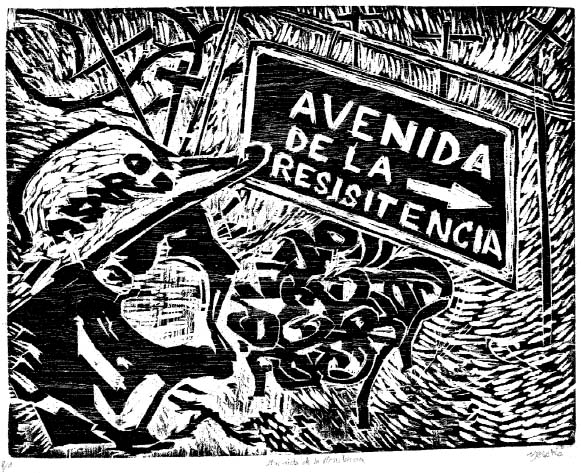

Avenida de la Resistencia, 2010, block print, 18.5 x 15.

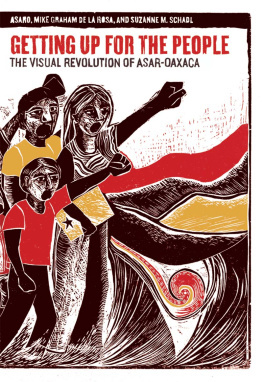

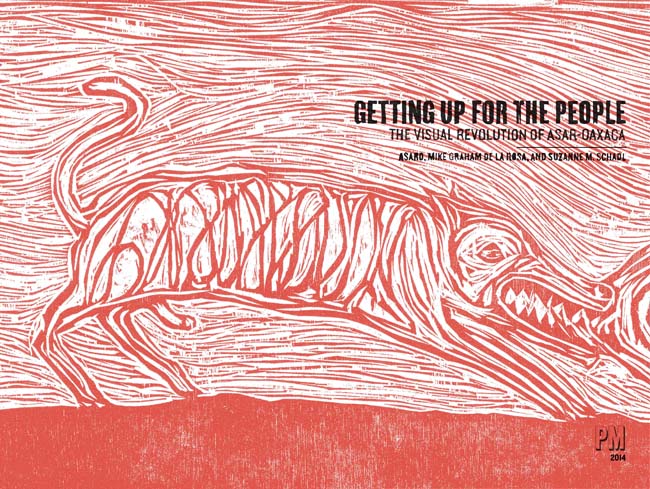

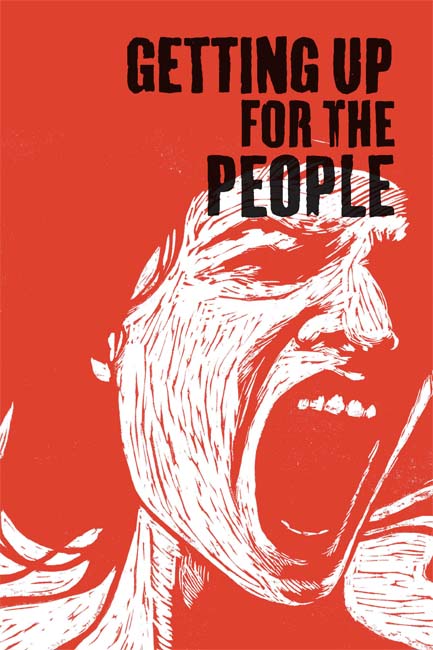

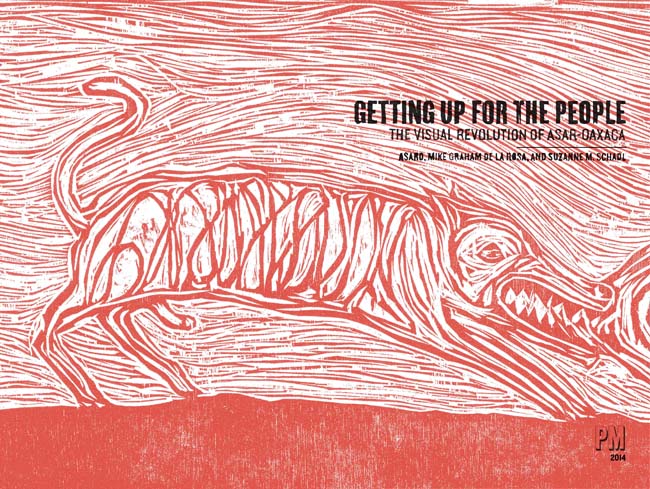

Getting Up for the People: The Visual Revolution of ASAR-Oaxaca

ASARO, Mike Graham de la Rosa, and Suzanne M. Schadl

2014 ASARO, Mike Graham de la Rosa, and Suzanne M. Schadl

This edition 2014 PM Press

ISBN: 978-1-60486-960-6

LCCN: 2013956915

Cover and interior design: Josh MacPhee/AntumbraDesign.org

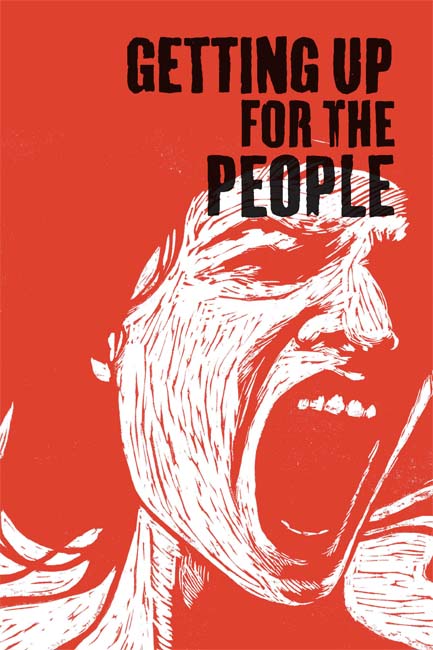

Cover image: La Comuna de Oaxaca 2006, 2006, block print

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press, PO Box 23912, Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA

CONTENTS

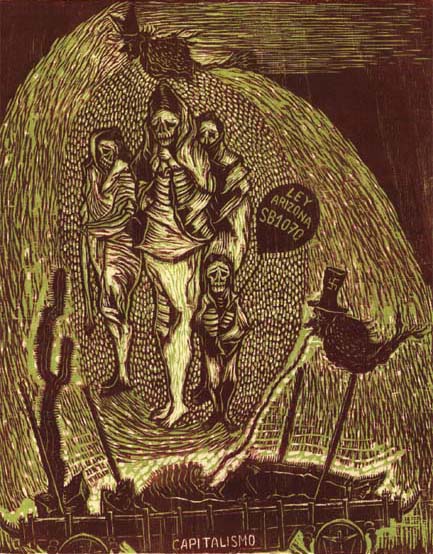

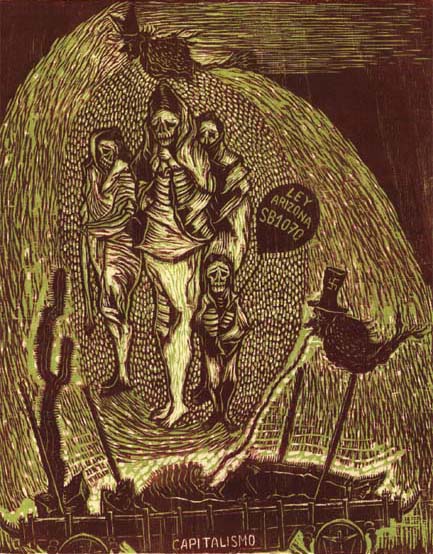

Arizona SB 1070, 2012, block print, 19 x 25 .

PREFACE

T his book was possible thanks to ASARO members past and present, many of whom cannot be named. All of the block prints reproduced herein are part of the Asamblea de Artistas Revolucionarios de Oaxaca Pictorial Collection at the Center for Southwest Research in the College of University Libraries and Learning Sciences at the University of New Mexico (UNM). This collection was established in 2010, which is why many of the of the prints have been assigned that date. The photographs were generously provided by Itandehui Franco Ortiz. Unless otherwise noted, the prints depicted throughout this text are ASAROs. Between 2006 and 2008 ASARO included more people than could be counted here, and today only Mario, Cesar, Yescka, Ita, Irving, Chapo, Beta, and Line remain. For this reason, collectivity, community, social context, and articulation through print and image are more important than proper names in Getting Up for the People: The Visual Revolution of ASAR-Oaxaca. As ASARO does, this catalog visually remixes the Oaxacan past with its present and exhibits how this contemporary Mexican artists collective weaves global humanist themes throughout its work. As fliers, posters, and wheat pastes, these images are applied in the streets, inviting people to communicate with themsometimes by adding a visual twist, or by taking a second glance. Responses can be good and bad; what is important is that they elicit an active dialogue. As collectible prints, these images are paradoxical parts of the outward-looking Oaxacan cultural industry. They invite people outside of Oaxaca to look beyond the veneer of a quaint colonial-like city and to see people struggling, while telling their stories through art and print. Getting Up for the People is another vehicle for that important dialogue.

Todo el Poder al Pueblo APPO, 2006, stencil and graffiti.

I think we first used arte pal pueblo in 2006, and our language is Western. Sometimes we use that word art, and we dont define its meaning. Every individual gives it meaning, and thats whats important. For me, it was essential to communicate with society, the marginalized, who are our neighbors, who we pass every day in the streetthe humble working people, not the rich. The rich exploit people, but its the humble people that make things happen. I think thats what pueblo is. Anonymous

INTRODUCTION: MANIFESTING VISUAL REBELLION

ASARO is a gathering of artists from various artistic disciplines which creates public art for the purpose of restoring social order. ASARO Manifesto

T his first statement in the manifesto of the Assembly of Revolutionary Artists of Oaxaca (ASARO) does not explicitly state the importance of Oaxaca. The state is intrinsic, however, to ASAROs identity as a community creating art for the peoplearte pal pueblo. Written amid the heat of battle against then-governor Ulises Ruiz Ortiz (URO), this statement was intended to express the collectives belief that Ruiz Ortizs removal was the key to restoring social order. Ruiz Ortizs success in maintaining his position through 2010 set a steadier flame burning. Eight years later, ASARO now teaches stenciling and printing techniques to young people from Oaxacas impoverished municipalities and encourages them to translate their histories, perspectives, and social grievances into creative visual exchanges with other Oaxacans and anyone else who circulates through the capital city, Oaxaca de Jurez.

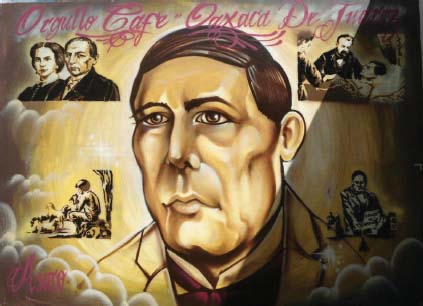

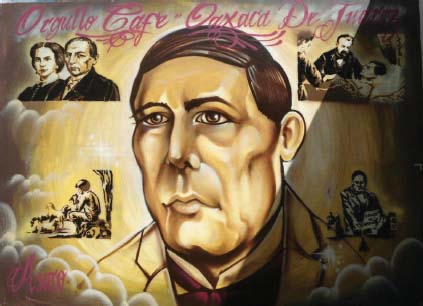

The birthplace of Benito Jurez, Mexicos beloved and only indigenous president from 1858 to 1872, Oaxaca is recognized for its indigenous peoples or pueblos. History suggests that Oaxacas second-largest contemporary indigenous power, the Mixtec, succeeded its largest, the Zapotec, during the postclassical period, only to fall later to the notorious Aztec civilization. Nevertheless, elements from all of these cultures survive today in Oaxaca, each incorporating other cultures. State officials recognize sixteen different indigenous groups with distinct languages, but others remain undocumented by officials. Named for the famous Zapotec president, the states capital city has long been the central nexus for trading from around the state; many cultures or peoples/pueblos converge on the central mercado, making it a sensory overload for some and an attraction for others. Tourists from throughout Mexico and from other countries frequent this space, often because of its indigenous population.

Jurez Pride Caf, 2013, graffiti mural.

The people here are represented as a little savage. Mass media does not reveal the truth; its always disguised. They show the colors of our pueblos, like they do in celebrations of the communities. Its a way for the state to make money, though and its a form of exploiting that image of our state and these communities in other states. Ita, ASARO

For officials in Mexico, the unmarked veneer of Oaxaca de Jurezs historic center attracts visitors by offering them a seemingly authentic confluence of Mexican cultures, past and present. The Oaxacans represented in these contexts are dressed in colorful and intricately woven costumes and carry forward enduring, ancient traditions. Festivals like Julys Guelaguetza, in which indigenous participants from different regions of the state gather around a collective celebration of Oaxacas diverse cultures, are another highlight for Oaxacan tourism, and people have reclaimed it as their own since Ruiz Ortiz left public office. Disrupting these tourist spaces with contradictory messages of conflict, as in Ulises Si Cay (Ulises Did Fall) reveals the inconsistencies between the states manufactured bucolic image and the actual experiences of its peoples.

In 2006, Oaxaca de Jurez was turned upside down when the governor, with the support of Mexicos president, sent in riot police to silence teachers protests against poor pay and inadequate resources. On June 14, the Federal Preventative Police (PFP) at the behest of the Oaxacan governor and the Mexican president attacked protesting teachers and supporters with tear gas, and helicopters circled overhead. By the end of the day, ninety-two people had been seriously injured and four unarmed teachers were dead. Shocked and disgusted, city residents joined the teachers the next morning to raise barricades against the police. They also assembled a collective resistance comprised of indigenous organizations, womens groups, rural workers, religious activists, students, human rights organizations, and artists under the umbrella of the Asamblea Popular de los Pueblos de Oaxaca/Popular Assembly of the Peoples of Oaxaca (APPO).

Next page