Contents

Guide

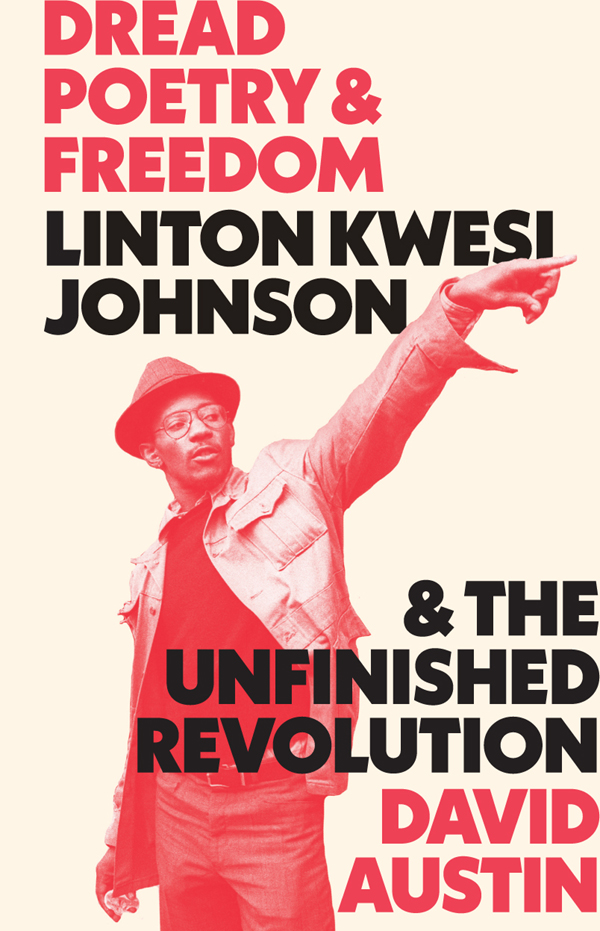

DREAD POETRY AND FREEDOM

David Austin offers nothing less than a radical geography of black art in his (re)sounding of Linton Kwesi Johnson. You dont play with Johnsons revolutionary poetry, Austin teaches, and Dread Poetry and Freedom is as serious, and beautiful, as our life.

Fred Moten, poet, critic and theorist

A moving and dialogic musing on freedom. Austins richly textured study reads LKJs poetry in relation to an expansive tradition of black radical politics and poetics. It captures both the urgency of Johnsons historical moment and his resonance for ours.

Shalini Puri, Professor of English, University of Pittsburgh

With the intensity of a devotee and the precision of a scholar, David Austin skilfully traverses the dread terrain of Linton Kwesi Johnsons politics and poetry, engaging readers in an illuminating dialogue with diverse interlocutors who haunt the writers imagination.

Carolyn Cooper, cultural critic, author of Noises in the Blood: Orality, Gender and the Vulgar Body of Jamaican Popular Culture

Dread Poetry and Freedom offers an expansive exploration of Caribbean political and cultural history, from Rastafari in Jamaica and Walter Rodney and Guyana to the Cuban Revolution with impressive articulations of the significance of Fanonism. Caribbean political theory is animating literary and cultural studies diasporically; this work demonstrates this elegantly.

Carole Boyce Davies, author of Caribbean Spaces, Professor of Africana Studies and Literature at Cornell University

For Mshama and Alama

In memory of my grandmother, Ms. James and Aunt Pearl

and

Richard Iton, Franklyn Harvey, Abby Lippman

and Myrtle Anderson

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

To quote the words of Sam Cooke, Dread Poetry and Freedom: Linton Kwesi Johnson and the Unfinished Revolution has been a long time coming. I would like to thank the team at Pluto Press, and especially editor David Shulman, for his support and trust in the outcome.

Yael Margalit graciously read the entire manuscript and I am very fortunate to have benefited from her precision and keen insights on poetry and the English language. Malik Nol-Ferdinand provided critical feedback on related to Walter Rodney and Guyana. Many students have sat through my Poetry and Social Change courses at John Abbott College over the years as some of the books ideas were reconsidered in the classroom. I would especially like to signal Maranatha Bassey and Stefan Florinca who helped to keep the class alive as I stumbled my way through that very first course in the winter of 2013, and Katya Stella Assoe, Anne Bojko, and Diego Ivan Nieto Montenegro who affirmed, without them realizing, why I was writing this book.

Friends, family and colleagues have been a presence, suffered through my musings, or offered, often unaware, words of encouragement, disagreement, and insight on poetry, politics, music, and theory. I would like to mention the following: Amarkai Laryea and dbi young anitafrika, both of whom were present when I first embarked on writing this book in Havana; Ceta Gabriel, Vincent Sparks, Amanda Maxwell, Cleo Whyne and Garth Mills, and the rest of the old Youth in Motion crew who are always in my thoughts. Robert Hill, a friend and scholars scholar. Mariame Kaba, for among other things, putting up with my incessant play of LKJ many years ago; Nigel Thomas and the Logos Readings (formerly Kola); Binyam Tewolde Kahsu and Anastasia Culurides, Nantali Indongo, Kai Thomas, Amarylis Gorostiza, Xismara Snchez Lavastida, Teeanna Munro, Karen Kaderavek, Sujata Ghosh, Tamar Austin, Hyacinth Harewood, Shalini Puri, Roy Fu, Sarwat Viqar, Neil Guilding (aka Zibbs), Jason Selman, Kaie Kellough and Jerome Diman; Scott Rutherford, Patricia Harewood (thanks) and Pat Dillon; Koni Benson, Melanie Newton, Alberto Sanchez, Astrid Jacques, Kagiso Molope, Beverley Mullings, Samuel Fur, Peter Hudson, Sunera Thobani, Sayidda Jaffer, Aziz Choudry, Ameth Lo, Stefan Christoff, Isaac Saney, Dsire Rochat, David Featherstone, Karen Dubinsky, Paul Di Stefano, Eric Shragge, Hillina Seife, Frank Francis, Kelly McKinney, Aaron Kamugisha, Irini Tsakiri, Minkah Makalani, Karen Dubinsky, Candis Steenbergen, Frank Runcie, Mario Bellemare, Debbie Lunny, Alissa Trotz, Sara Villa; Rodney Saint-loi (le pote), Yara El-Ghadban for those many conversations on Mahmoud Darwish; Adrian Harewood and Ahmer Qadeer for checking in, and Shane Book, the poet among us.

I would also like to acknowledge my grandmother, Rose Denahy, my parents, Sonia Jackson and Lloyd Austin; Michael Archer and Norman Austin, Tony Denahy and Jeff Denahy childhood memories of music on Selbourne Road in Walthamstow, East London

Laneydi Martinez Alfonso has been a sounding-board and co-conspirer. She gave critical feedback on the manuscript and patiently listened to my late night ramblings on it. Qu hara yo sin ti?

The impending birth of my daughter Mshama was the initial inspiration for this book, and many years later she also assisted in transcribing interviews, including an interview with Linton Kwesi Johnson. My son Alama was perhaps once LKJs youngest fan who also alerted me to the profile resemblance between Johnsons image on the Penguin Modern Classics selection of his poetry and the image of Thelonious Monk on the album Monks Dream. He was also quick to remind me not to neglect the brilliant Jamaican poet Michael Smith as I wrote. This book is for both of you.

Finally, were it not for Richard Iton, this book, in all likelihood, would not have been written. His intellectual acumen was matched only by his sincerity as a friend. Richard, may your restless spirit continue to haunt us.

PREFACE

Several specific experiences directly influenced my motivation to write Dread Poetry and Freedom: Linton Kwesi Johnson and the Unfinished Revolution. Part of the books origins lie in South Africa, where in August 2001 I was part of a team that accompanied ten Montreal youth to participate in the World Conference Against Racism (WCAR). I had just finished an intense and exhausting three years of work with a youth organization in Montreal that plunged me into an existential crisis.

In this moment of deep introspection, I was forced to pose some difficult personal, political and organizational questions. Some of these questions touched on the relationship between theory and practice, the meaning of social change and the practical process involved in realizing change in an environment in which real lives are at stake. I was pondering these issues in South Africa as I visited sites where some of the most important rebellions and uprisings against apartheid had occurred, often with youth as young as those with whom I had worked with over the years in Montreal at the forefront. Organized by a local youth organization that specialized in the arts, the trip to South Africa was structured as an exchange in which youth from Montreal were paired with youth from Johannesburg-Soweto. The experience was an eye-opener for the youth who participated in it, and for the adults, and it provided an international forum to discuss the issues of race, class, colonialism and imperialism. Perhaps, were it not for the events of 9/11, the impact of the conference would have had more traction and far-reaching significance in its aftermath.

After a week participating in the WCAR in Durban we then travelled to Port Elizabeth, Cape Town, and finally back to Johannesburg where we had initially landed. As someone whose consciousness had been shaped by the anti-apartheid struggle and anti-apartheid reggae songs such as Peter Toshs Apartheid, and who had participated in the tail end of the global anti-apartheid movement as a university student, the trip put a face to the country that had once been infamous for its policies of white supremacy. I also gained a better understanding of the impact that apartheid had, and continues to have, on the entire society.