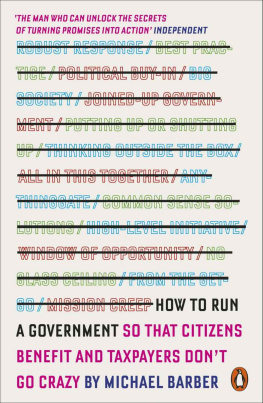

Michael Barber

HOW TO RUN A GOVERNMENT

So that Citizens Benefit and Taxpayers Dont Go Crazy

Contents

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Sir Michael Barber is the co-founder of Delivery Associates and Chief Education Advisor at Pearson. Over the last two decades he has worked on government and public service reform in more than fifty countries. From 2001 to 2005 he was the first Head of the Prime Ministers Delivery Unit in the UK. His previous books include Instruction to Deliver: Fighting to Transform Britains Public Services.

For Karen

Between the idea

And the reality

Between the motion

And the act

Falls the Shadow

T. S. Eliot,

The Hollow Men

Preface

Why do we need a book about how to run a government? Isnt the world already flooded with books about government? Arent there columnists in every serious newspaper and now a host of bloggers too churning out more political commentary, much of it excellent, every hour?

Well, yes there are, but surprisingly very few of the books and very little of the commentary focus on how to run a government so that it delivers the change it has promised. In fact, there is a gaping hole where this should be.

Governments errors, needless to say, attract plenty of attention (as they should); as does the practice of politics how to win and lose elections, how to gain and lose power which is endlessly fascinating; the fortunes of individual politicians as their ambitions are fulfilled or (more often) dashed are an endless soap opera; and, as thinking about government and politics advances, ideas are debated too, sometimes even at a rarefied level. But for some reason the practices of governments that succeed in making real improvements to the lives of their citizens attract very little attention.

Perhaps at first glance this is due to the way outcomes for citizens are ground out (and they usually are ground out), which looks a little dull compared to the gossip or the commentary or the controversy about a big idea. But in this book I aim to show that this is a totally false conception. The reality is that the process by which governments deliver results is not just fascinating, but also vitally important.

Why? Because, while what the president of the World Bank Jim Yong Kim calls the science of delivery the growing knowledge base about how governments can successfully deliver is new and a

Furthermore, history provides many examples of leaders of governments kings and emperors, as well as presidents and prime ministers who sought to improve the lives of their citizens and sometimes succeeded. As they did so, they werent aware that one day theyd provide the historical evidence for an emerging science of delivery; nor, generally speaking, were the historians and biographers who wrote about them. Yet by sifting through the stories of, for example, Theodore Roosevelt, Horatio Nelson, Mohandas K. Gandhi and Henry VII, king of England, all of whom appear in these pages, one finds there, among the debris of historical writing, just as an archaeologist does among ruins, artefacts which, once assembled, provide insight into how governments of the future can get things done, often against the odds.

Understanding how to run a government effectively is important because the success or otherwise of governments is fundamental to the prosperity and well-being of all of us, wherever we live. There is a tendency in the West, especially in the US, to see government as the problem, not least because a lot of the time government is hapless or worse. Government can be a problem, but you only have to look at what life is like when it breaks down to realize how important good government is.

Also, we fool ourselves if we set up a false dichotomy between markets and governments, since the functioning of one depends absolutely on the other. Whether government is big or small is a political choice that countries can make but, whatever your politics, the effectiveness (or lack of it) of government is immensely important. As Theodore

In short, the process of delivery is important to politics since democracy is threatened if politicians repeatedly make promises they dont then deliver; it is also important to citizens regardless of politics, because if government fails, their daily lives education, health, safety, travel and parks, for example, not to mention the effective regulation of markets are materially threatened. And it matters to the success of economies, at both national and global levels, because even where government is small, it takes up over 20 per cent of GDP. In many countries it is 40 or 50 per cent, and if it is unproductive it is a huge drag on economic growth. Moreover, as Matthew dAncona has argued, successful political leadership is becoming increasingly challenging as leaders face higher expectations of government, raised standards of accountability and media scrutiny more intense and unrelenting than at any time in history. The challenge is acute as these leaders attempt to reconcile citizens to the thunderous forces unleashed by globalisation.

The perspective of the book throughout is from the centre of government looking out. The aim is to convey to the reader what it feels like to be in there looking at the world beyond and trying desperately to get something done so that the citizen benefits. From the outside, people at the heart of government look all-powerful; on the inside, they often feel helpless, stretched to and beyond breaking point by the weight of expectations on the one hand and the sheer complexity and difficulty of meeting them on the other.

Political leaders of both talent and genuine goodwill, of which there are many more around the world than public commentary would have you believe, find themselves struggling to deliver their promises. Huge public bureaucracies, which is what government departments are, should in theory enable these political leaders to deliver outcomes for citizens; in practice they sometimes become barriers to implementation. It is in the interests of both transparency and understanding to describe, not just to experts but also to interested citizens, what these challenges are and how they might be overcome. This is the purpose of this book.

As we all know, habits are hard to change. In governments, with deeply ingrained cultures and in the full glare of constant media attention, changing culture is harder still. But if our governments and public services are to provide the services and regulation on which our prosperity as individuals and as a global community depends, their cultures and processes will have to change. The chapters in this book describe the challenge governments face and the vital processes which, if adopted by governments around the world, would make a huge difference to all of us. They are the foundations of a science of delivery.

Spread across the chapters are 57 Rules to follow. They are a summary of the main practical points in the book, and are gathered together, by chapter for ease of reference, in the Appendix.

Introduction: The Missing Science of Delivery

FOUR CHARACTERS: ONE PROBLEM

Viktor Chernomyrdin was the prime minister of Russia in those heady, rollercoaster years of the 1990s after Communism had collapsed and before Putin imposed his steadily tightening stranglehold. Throughout the ups and downs of his time in power, Chernomyrdin somehow kept his sense of humour, remarking on one occasion: We keep trying to invent new organizations, but they all turn out to be the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and on another: Its never been this way before and now its exactly the same again. In spite of the hardships they endured, therefore, the Russian people had an affection for him that none of his predecessors or successors has enjoyed (or deserved, one might add).