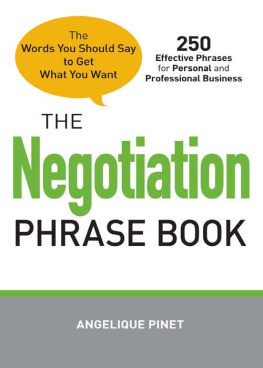

Negotiation

An A Z Guide

Gavin Kennedy

THE ECONOMIST IN ASSOCIATION WITH

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

Published by Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House, Pine Street, London EC1R 0JH

THE ECONOMIST IN ASSOCIATION WITH

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

Published by Profile Books Ltd

3A Exmouth House, Pine Street, London EC1R 0JH

Copyright The Economist Newspaper Ltd 2004, 2009

Text copyright Gavin Kennedy 2004, 2009

Developed from titles previously published as Pocket Negotiator and Essential Negotiation

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or

introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of both the copyright owner and

the publisher of this book.

The greatest care has been taken in compiling this book.

However, no responsibility can be accepted by the publishers or

compilers for the accuracy of the information presented.

Where opinion is expressed it is that of the author and does not necessarily

coincide with the editorial views of The Economist Newspaper.

Designed by Sue Lamble

Typeset in EcoType by MacGuru Ltd

info@macguru.org.uk

Printed and bound in Great Britain by

Bookmarque, Croydon, CR0 4TD

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library

ISBN 9781847651198

Preface

This book was conceived as a handy aide-mmoire for those engaged regularly in negotiation and who on occasion want to consult a practitioners guide to the many facets of negotiating practice that they confront across the table from time to time. It is neither a theoretical treatise nor an account of the war stories of how the worlds experts conducted themselves.

It is a practical and, I hope, informative guide to the real world of business negotiating. It is about negotiating as it happens, not how it might appeal to fiction scriptwriters or people who imagine the whole world is out to get you with bluff and fraud strategies, Machiavellian duplicity, and complex bluff and double-bluff intrigue. That view of business is best left to imaginative voyeurs. Bluffs as tactical tools tend to be counter-productive.

In the AZ section several bluff tactics and ploys are identified to arm you for what you might come across from time to time a ploy identified is a ploy neutralised, because for every ploy ever tried there is always a counter. For ease of use, cross references are identified in SMALL CAPITALS but common abbreviations, such as EU or ACAS , may not have separate entries.

Numerous people influenced my negotiating work over the past 36 years too many to acknowledge here. My singular and main debt remains to my late friend and partner, John Blair Benson, formerly chairman of our international consultancy, Negotiate, which is now managed by my daughter, Florence, who has opened new markets and new clients since she took over. I am sure she would have got on well with John, for he took to and respected hard-working, professional negotiators. He wasnt sympathetic to the other kind, who usually neglected to practise the use of the conditional (If you then I) and who failed to prepare for their negotiations. (Preparation, he often said, is the one task where negotiators may ethically gain an advantage over the other party.)

Negotiators who follow Johns advice perform better than those who dont.

Gavin Kennedy

Edinburgh

A brief history, and future, of negotiation

Negotiation as a social transaction between humans has a long history. It developed slowly from fairly primitive bargaining between pairs of people as human societies evolved from small hunter-gatherer bands of a few dozen people living in the vast expanse of the earths continents through to the revolution in agriculture and pastoral practices about 8,00011,000 years ago. Villages and little towns began to appear in the northern Eurasian land mass and spread south-east to India and east to China as farming was imitated and landlords congregated for protection. The history of agriculture for several millennia continued with a mixture of hunter-gathering and small-scale farming in western Europe and the great agricultural empires of Egypt, Babylon, India and China, based on proximity to large rivers and large-scale irrigation schemes.

European trade spread among villages and small towns and their rural hinterlands, creating traders, artisans and marketplaces, which slowly created the commercial economies of Europe. These were followed eventually by the so-called industrial revolution in Britain in the 19th century on the back of technologies (some of them known to, but not exploited by, China centuries earlier). The inhabitants of the cities were now counted in tens of thousands and national populations in a few million (tens of millions in China).

With industrialisation, markets matured on scales unknown even in the earliest commercial societies of the Greek and Roman Mediterranean and the long-distance trading routes between Arabia, India and China. Manufacturing and the division of labour on an increasingly global scale brought negotiation to its most refined and complex forms by the 20th century. Contact among neighbouring populations refined negotiating diplomacy at government levels, and in the formulation of state policies towards neighbours and within systems of justice. Wars were ended in outright victory or peace negotiations and future accommodations between victors and vanquished. Treaties of peace, marriage treaties between rulers and complicated succession and inheritance disputes brought negotiation practice into all aspects of civil government.

Traditional negotiation

The essential common structure of negotiation remained as it had always been: two parties meeting as principals or through representatives exchanged their different solutions to the common problem both parties faced, until a common solution acceptable to both sides was reached or the parties broke off in frustration or discord.

The essential common factor of all negotiations was the resolution of the conditional offer: Give me that which I want, and you shall have this which you want (Adam Smith, 1776). Each side modified its demands or increased its offers, and, perhaps, introduced new tradables, until a common acceptable solution was reached, or they both failed to agree and sought what they wanted from somebody else. This defines traditional negotiation as: the process by which we search for terms to obtain what we want from someone who wants something from us.

In the AZ section there are illustrative references to some experiments with alternative reforms or additions to traditional negotiation and comments about their practicality. But overall, I do not expect the existing negotiation process to change much in the foreseeable future. Indeed, this book is largely about the traditional form that negotiation takes in todays world and what it has evolved into over thousands of years, as people explored less bloody and destructive ways, which were common among our predecessors, as they set about redistributing the bounties of nature and the fruits of labour.