2016 by Nathaniel R. Jones

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to: Permissions Department, The New Press,

120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Excerpt from I, Too from The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes, edited by Arnold Rampersad with David Roessel, associate editor, copyright 1994 by the Estate of Langston Hughes.

Used by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday

Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2016

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-071-3 (e-book)

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Names: Jones, Nathaniel R., 1926 author.

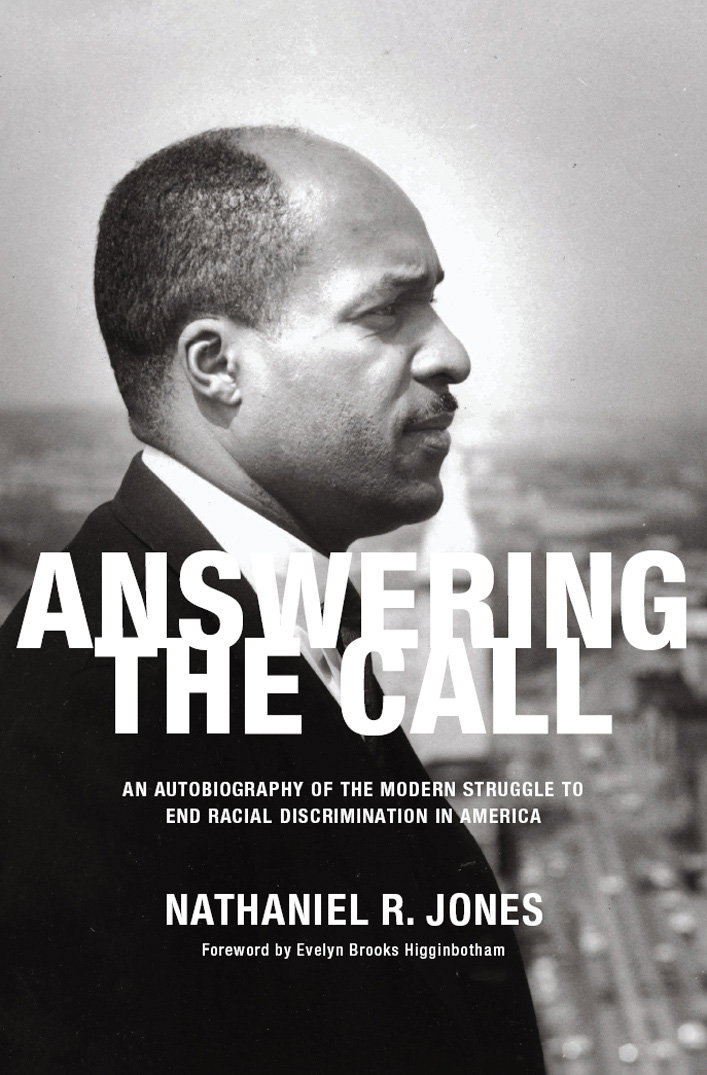

Title: Answering the call: an autobiography of the modern struggle to end racial discrimination in America / Judge Nathaniel R. Jones; foreword by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham.

Description: New York: The New Press, 2016. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015043150

Subjects: LCSH: Jones, Nathaniel R., 1926 | JudgesUnited StatesBiography. | Civil rightsUnited StatesHistory. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Lawyers & Judges. | LAW / Civil Rights. | HISTORY / United States / 20th Century. | HISTORY / United States / 21st Century.

Classification: LCC KF373.J64 J66 2016 | DDC 347.73/2434dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015043150

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Composition by Westchester Publishing Services

This book was set in Adobe Caslon

Printed in the United States of America

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

To thosemy parents; my beloved late wife, Lillian;

J. Maynard Dickerson and other mentors and colleagues

from my earliest years to the presentwho believed

in my capacity to answer the call

Table of Contents

Guide

Contents

by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham

I came of age during the classic phase of the civil rights movement, years when marching and nonviolent direct-action protest took on enormous visibility as powerful and effective weapons for social change. The previous eras legalistic approach, exemplified in the court cases that led to and included Brown v. Board, seemed to me and my generation a bit too slow and old-fashioned. The movement in the 1960s was dramatically brought into our own homes through television and other media coverage. We watched the footage of the many events with the same depth of personal emotion and concern that people today watch the videos recorded on phones that catch outrageous acts of brutal injustice. Who can forget the image of James Merediths entrance into Ole Miss, the firebombed bus of the Freedom Riders, the vicious police attacks on peaceful but unswerving protesters in Birmingham, the eloquent plea of Martin Luther King Jr. at the triumphal March on Washington for the passage of a civil rights act, and the courageous Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee workers along with the indomitable Fannie Lou Hamer in the Southern voting registration drive of Freedom Summer? Whether witnessed in person or via the media as they occurred, such images were branded on our minds. They will never be forgotten.

Yet we have forgotten, if we ever knew at all, the lawyers who played crucial roles in those events. In the 1960s my generation of activists certainly underemphasized, if not undervalued, Constance Baker Motley of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, who argued and won the court battle over Merediths right to enroll at the University of Mississippi and who walked beside Meredith along the dangerous, heckler-laden path to the schools registrar. Nor did we credit at the time the prowess of the NAACP lobbyist and lawyer Clarence Mitchell in the formulation and successful passage of the congressional legislation that became the Civil Rights Act of 1964. In like manner, my generation of activists boldly voiced our solidarity with the Third World, with the people of color in Asia and Africa who had attained independent nationhood after World War II or found themselves still in the throes of anticolonial struggles in the 1950s and 1960s, and yet we neither recognized nor understood the significant earlier interventions of Walter White and the NAACP in those anticolonial struggles in the late 1940s. This knowledge would come many years later.

Because of the burgeoning scholarship in the past three decades, I have been made keenly aware of my earlier ignorance and have learned as a professor of history to look for continuities over greater periods of time. The long civil rights movement, according to current studies, encompassed several generations of struggle from the 1930s through the 1970s. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the autobiography of Nathaniel R. Jones, since the vitality of his legal work proved relevant for each generation of activists. Several themes run through the book in this regard. The Northern side of the civil rights movement represents a theme vividly portrayed. Joness autobiography underscores the emphasis of contemporary historians who call attention to a decades-long protest tradition of blacks in cities outside the South for equal access to public accommodations, for integrated schools and the end to racial disparities in educational resources, and for jobs and housing. Another theme concerns the persistent relevance of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Contrary to images of an elite, top-down organization that grew increasingly out of touch with the pulse of social activism in the 1960s and 1970s, the NAACP continued during those decades to be at the heart of civil rights challenges. A membership-based organization, the NAACP through its general counsel Nathaniel Jones took up the legal fight of ordinary men and women who sought a better life for themselves and their children.

Jones was hardly out of step with later generations of activists. Of his years as general counsel for the NAACP between 1969 and 1979, he writes, I established my reputation on the steady wave of issues that emerged involving student protests, military justice, school desegregation, employment and housing discrimination, and police excesses. In the late 1960s, when students like myself joined with other black students both in predominantly white and in historically black colleges and universities to demand Black Studies in the curriculum, the supportive action of the NAACP saved the day for the protesting students at San Fernando State College in 1969, after general counsel Nathaniel Jones arrived to defend them in court. During the era of black power, Jones had overall responsibility for the historic constitutional cases of public school desegregation (often reduced to the description of mere school busing cases by racist school districts) in Detroit, Cleveland, and Boston. Particularly striking in bridging the 1930s and 1970s is the story of the last Scottsboro Boy, Clarence Norris, who while a fugitive from the law finally won his pardon in 1976 from Governor George Wallace of Alabama through the NAACPs carefully devised legal strategy.