Lee H. Hill Jr.,

my father, who taught me to love history,

and for the Delany sisters,

from whom I learned history firsthand

I screamed murder with all my voice.

Elizabeth Jennings, 1854

L ANGUAGE IS NEVER STAGNANT. The meaning and intent of words can change over time. That is the case with the word colored, which is not accepted today because it has evolved into a loaded word meant to be racist and hurtful.

Colored was once commonly used to refer to black or African American people. African Americans frequently used the word colored in Elizabeth Jenningss era. The Colored American, for example, was a black newspaper in New York founded in 1837. Other examples of the use of the word by the African American community include the First Colored Presbyterian Church and First Colored American Congregational Church, churches in New York City. Frederick Douglass used the term colored in his publications, several of which are quoted from in this book.

Readers may also note that the term civil rights, which is a common phrase describing the struggle for equality among races, has been replaced with equal rights for blacks to avoid confusion. Historically civil rights is a term used mainly to describe the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s, not the 1850s.

Some readers will no doubt be curious about the emphasis put on social class by the primary sources referred to or quoted from in this book, including Elizabeth Jennings, who refers to herself as respectable and genteel. This was typical of the way members of the middle class, both white and black, described themselves in the era.

Other words, archaic in meaning today, are explained in the text or in footnotes when needed.

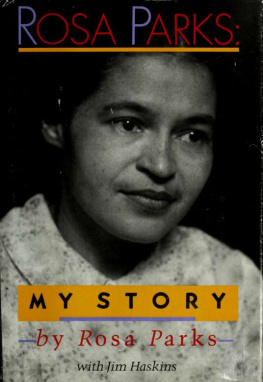

The only known photograph of Elizabeth Jennings.

M ISS ELIZABETH JENNINGS had a job to do.

She had to get to the First Colored American Congregational Church, where she was the organist. The choir would be waiting for her. They rehearsed each Sunday afternoon, and having the organist accompany them was essential.

But on this particular Sunday she never arrived.

This was surprising. A schoolteacher as well as an accomplished musician, Elizabeth Jennings lived a well-ordered life. In her twenties and unmarried, the youngest of several children, she lived at home with her father, Thomas L. Jennings, and mother, also named Elizabeth, at 167 Church Street in Manhattan. The Jennings family was part of New York Citys small black middle class and was active in civic and religious organizations that promoted the education, well-being, and rights of the citys black population.

There was no way of knowing, of course, that this would be a day like no other, that soon she would become embroiled in an incident involving several men she would later call those monsters in human form. The days events would change her lifeand, as it turned out, the path that history has taken.

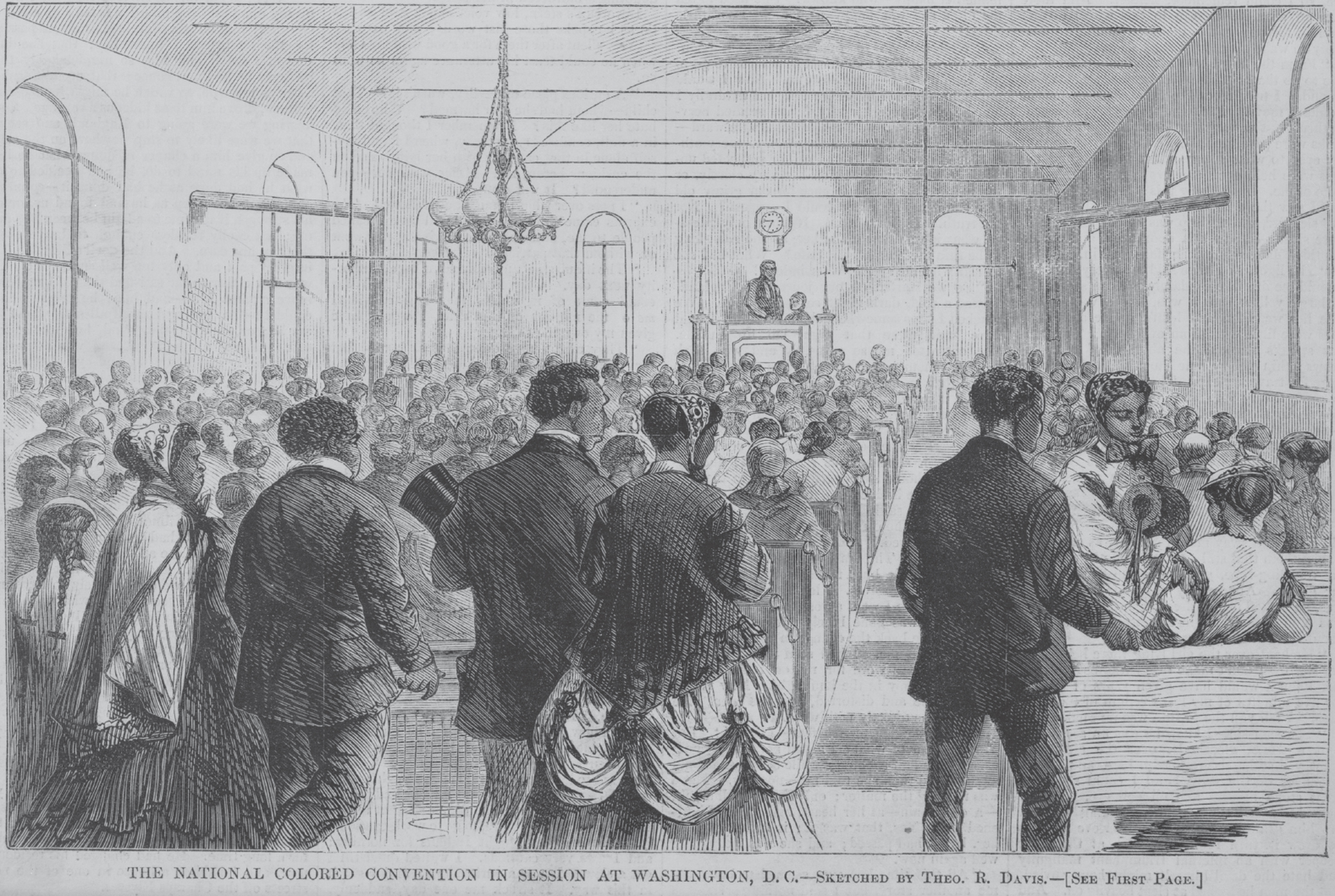

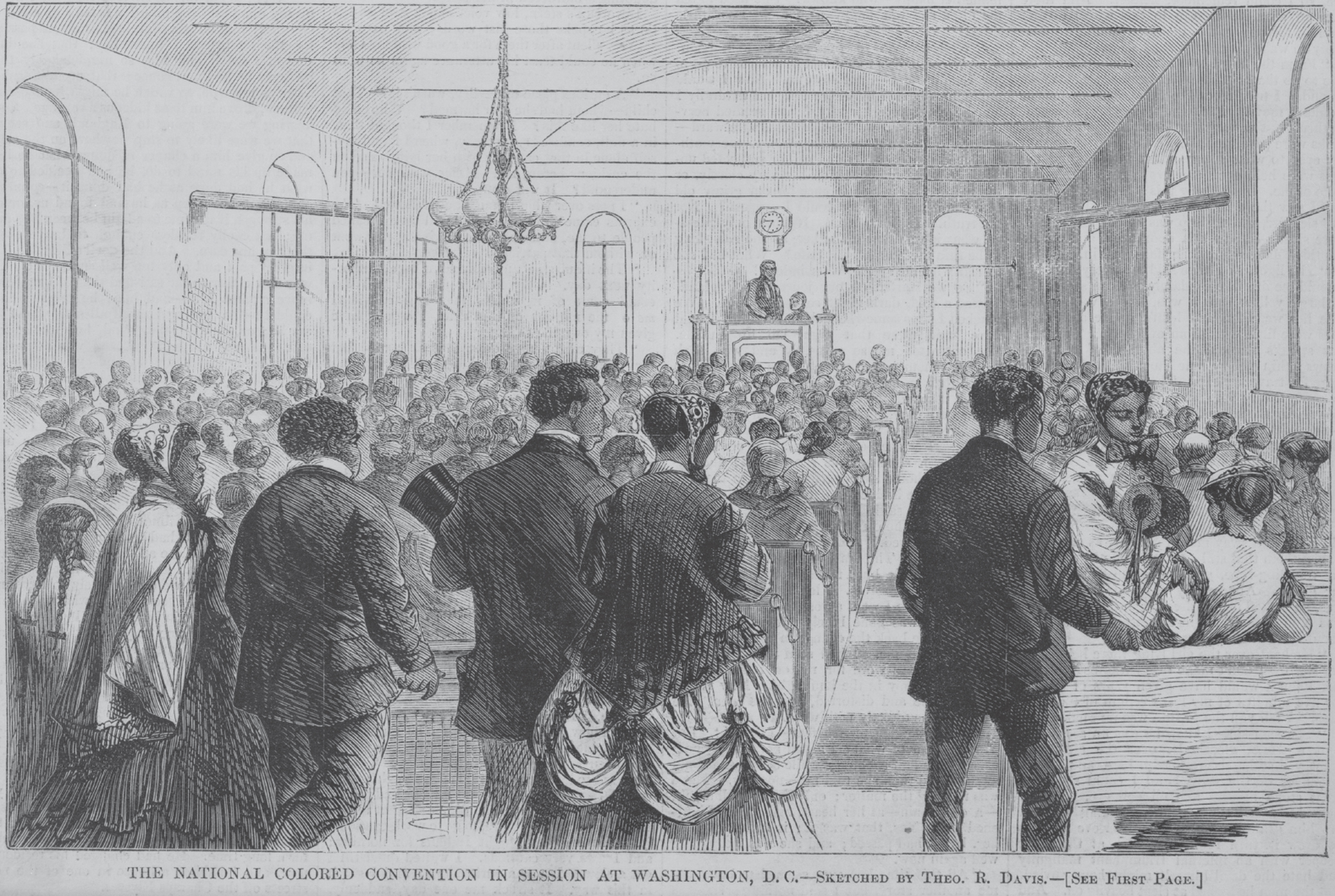

A gathering of black activists in the mid-1800s.

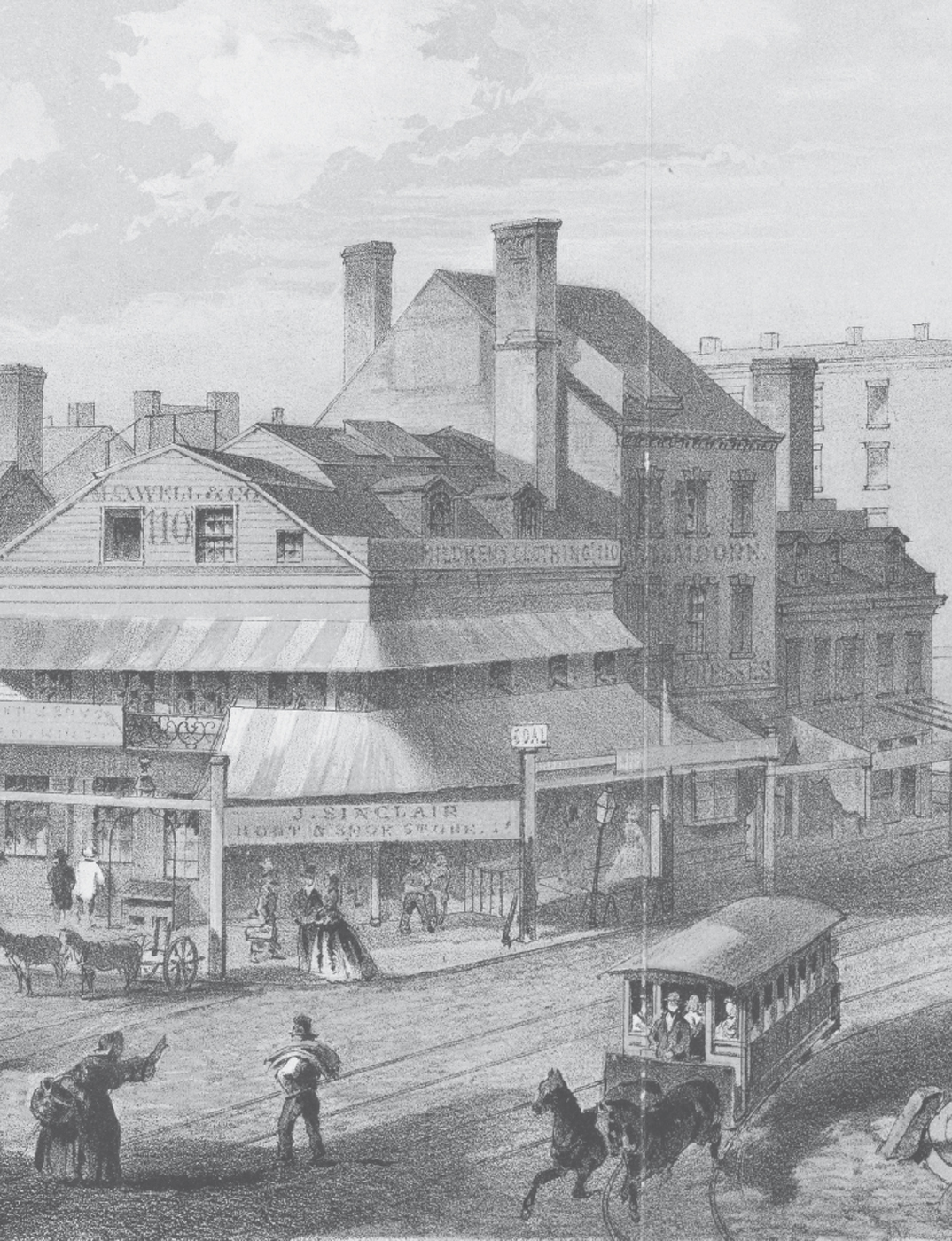

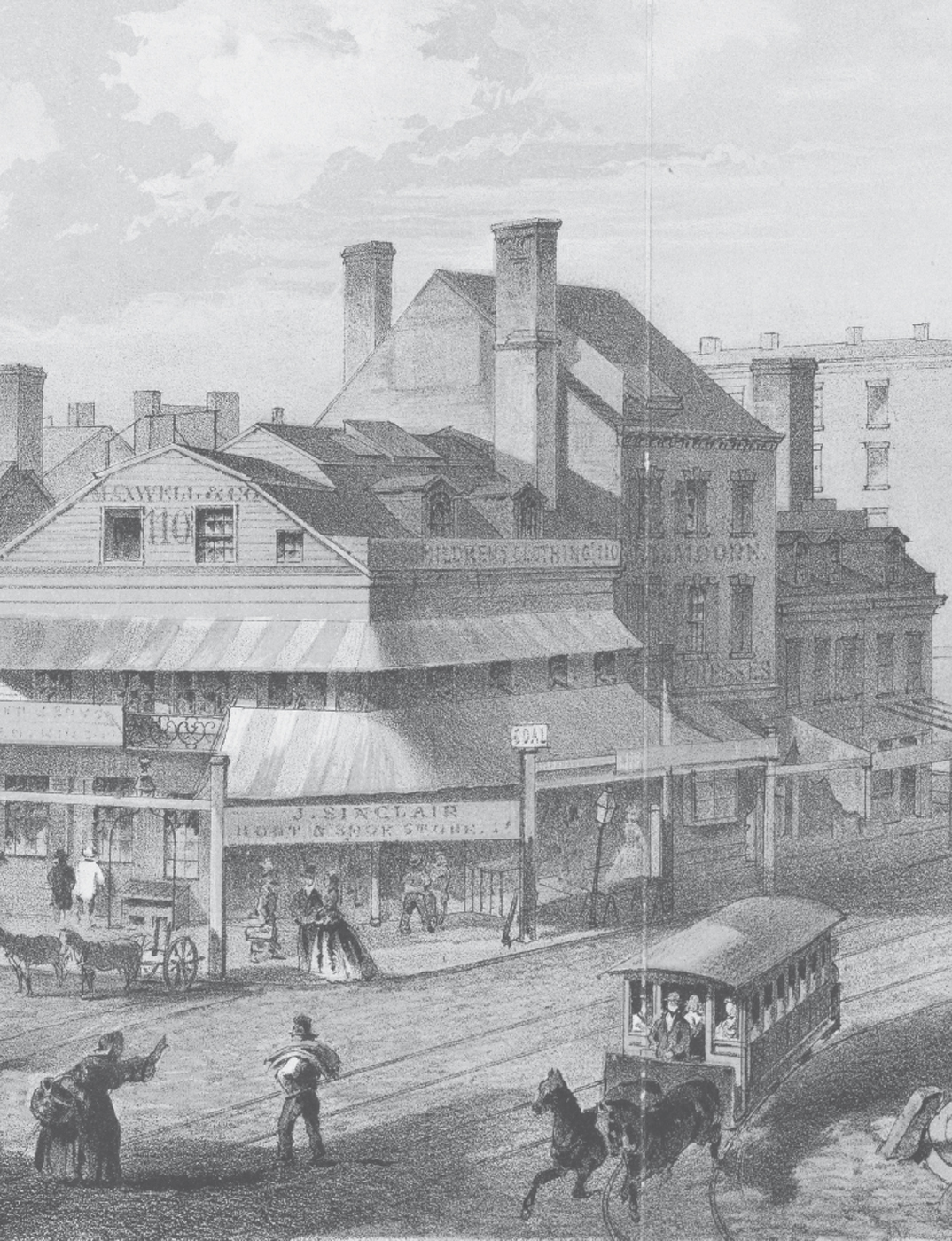

An 1852 drawing of New York (Manhattan). At the right of the drawing is Brooklyn, then a separate city.

Traveling to church meant a short walk followed by a ride on a streetcar. As she made her way to the streetcar stop, her only concern was being late.

The date was July 16, 1854.

And the place, New York City.

NEW YORK WAS NOT the city it is today, where tall buildings seem to reach into the clouds and subways whisk people from place to place.

There was no Brooklyn Bridge or Statue of Liberty in 1854. They hadnt been built yet. The same was true of the Empire State Building and Rockefeller Center. Times Square, then called Long Acre Square, was only partially developed.

New York City was made up of Manhattan only. The heavily forested area north that became the Bronx was then a part of Westchester County. Brooklyn was a separate city. Queens was still largely farmland, although factories were starting to be built. On Staten Island a manufacturing boom had not yet begun. Staten Island residents worked mainly on farms or at sea.

The city that Elizabeth Jennings lived in was much smaller, and much dirtier, than it is today. Many roads were unpaved. Some were made of cobblestone. Sidewalks existed in some places but not others.

As she made her way to the streetcar stop at what was then the corner of Pearl and Chatham streets (now the corner of Pearl Street and Park Row), she would have walked around piles of horse manure and maybe even the bloated remains of a dead animal or twofrequently a horsethat had been left to rot. It wasnt uncommon for two to three feet of garbage to be piled up in front of buildings.

To make matters worse, women of the time wore long dresses that came down to the ankle. Elizabeth had to navigate these streets while trying to keep the hem of her dress clean.

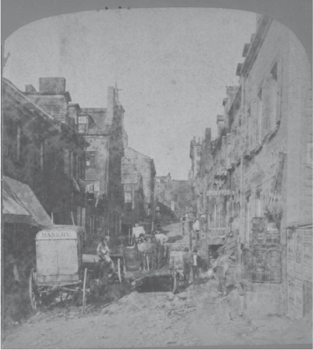

A photograph of a crowded and filthy street in Five Points.

This was not harmless dust. This was foul, disgusting dirt. Dangerous dirt that was full of germs. Thats because there was no indoor plumbing and no city-wide sewer system. Most people lived in four- or five-story apartment buildings and shared crude outhouses with as many as a hundred other residents. Elizabeths parents owned their home, which meant the Jennings family probably had a private outhouse (called a privy) in a very small backyard.

When it rained, the roadways turned into mud almost instantly. Carriages and wagons became stuck for hours. Raw sewage floated down the street.

On that particular afternoon, as Elizabeth walked to the streetcar stop, rain was not the concern. In fact, there was a drought. In the countryside crops were failing. In the city the air stank and was filled with grit and dust.

Even at the best of times life in the city was very hard for most people. Disease was a regular concern. Deadly cholera epidemics occurred almost every year, including an 1849 outbreak that killed five thousand New Yorkers. Typhus was epidemic in 1852. Tuberculosis was a constant threat. More than half the babies born in the city died before their first birthdays.

The rowdiest, unhealthiest, and most dangerous part of Manhattan was a neighborhood called Five Points, which had such a bad reputation that it had become well known around the world. During a visit to America the famous English author Charles Dickens compared Five Points with the worst slums of London, which he had written about in novels such as