One of the most rewarding and sustaining odysseys of writing Americas First Freedom Rider has been the generosity of the librarians, researchers, historians, authors, lawyers, professors, and public servants I met over the last twelve years.

Invariably, after quizzical looks, sighs, and head scratches, all enthusiastically embraced the challenge of helping me uncover the lives of forgotten and marginalized historical figures. Without their dogged determination and expertise, this project would not have come to fruition. Im eternally grateful for all their efforts and hope acknowledging them here brings some recognition to the great work they do daily.

Laboring in vain is the lot of any literary agent. Emily Williamson developed a knack for whispering into hurricanes and getting her clients message across. Im always amazed and grateful for her fearlessness and friendship. To all the folks at Lyons Press, Rowman & Littlefield, you have my humble gratitude Kudos to my crackerjack editor, Stephanie Scott. With a surgeons touch and a lumberjacks whack she put the sizzle on the steak and killed all the darlings for me. Didnt hurt one bit. Honest.

Its always risky talking to attorneys. You never know when the billable hours start. Special thanks to William Manz of St. Johns Law School; Ralph Monaco and Mikhail Koulikov from the New York Law Institute; Judge Al Rosenblatt and Bill Nelson, professors and legal historians at NYU Law School; Richard Tuske, NYC Bar Library; Marc Bloustein from the Historical Society of the New York Courts; and Jacqueline Cantwell, law librarian for the Brooklyn Supreme Court. An extra shout-out to patent historian Zvi Rosen, who generously shared Elizabeth Jenningss probated papers.

Historians are a collegial group, and many were an enormous help: Emilyn L. Brown, NYU; John Hepp, Wilkes University; Sarah Gronningsater from the University of Pennsylvania; Katherine Perrotta, Mercer University; and Lisa Keller of SUNY Purchase. Thanks also to regional historians Jody Clark of Gardiner, Maine; Trisha Dolton, Greenwich, New York; Lynn Humphrey, the Timothy Thomas Fortune Foundation; Marcella Micucci, MCNY, curator of the Rebel Women exhibit; Kaitlyn Greenidge, the Weeksville Heritage Center; and Johnathan Olly, the Long Island Museum To Andrew Unsworth, Susan Ackoff-Ortega, African Burial Ground Project, and Ken Rockwell for sharing his family history, thanks as well.

Good reference librarians are worth their weight in gold, and I hit the mother lode with every trip I made to these institutions. The NYPLs Schomburg Center was outstanding, as were the folks running the Pincus and Firyal Map Room and the Milstein Microform Room. I spent many Saturdays in the New-York Historical Societys research library, where Eric Robinson gave me the white-glove treatment (you cant touch some items without them). Hats off to my hometown library for reeling in faraway books and to Godlind Johnson of the Stony Brook University Engineering Library Likewise, to Olga Arena of Cypress Hills Cemetery and Jamie Hammons of St Philips Church, cheers.

Id be remiss not to mention Peter Aigner of the Gotham Center, who has boundless enthusiasm for local history, and my Wine Box Crew critic compatriotsChristine Alderman, Samika Swift, and Yolanda Ridge. To TM and MS, thanks for believing. To old buddy Stew ONan, who read numerous iterations of this manuscript and quite casually thought of the books title, thanks, man.

My daughter Gabrielle reanimated my creativity and helped me see the world in new ways; shes always extraordinary. To my wife, Camille, who made it easy to go storm the castle, you had me at hello, and still do.

Are we fallen angels who didnt want to believe that nothing is nothing and so were born to lose our loved ones and dear friends one by one.

J ACK K EROUAC ,

T HE D HARMA B UMS

T HEY SAY THE THIRD TIMES THE CHARM, AND IN THIS CASE, IT WAS A GEM. Chester A. Arthur didnt live long enough to see his only grandchild, Chester Alan Arthur III. But if he did, its highly unlikely they would have been kindred spirits. Where Chester lived for anonymity, Gavin, as he liked to be called, wanted center stage.

Without one, we would likely have limited knowledge of the other. Born and bred in sooty Manhattan, Chester II (also known as Alan) suffered from asthma and relocated to a 250,000-acre ranch in Colorado Springs. The cattle, mining, and timber from his investment ensured he didnt have to work a desk job like his father. His son Chester Alan Arthur III was born there on March 21, 1901.

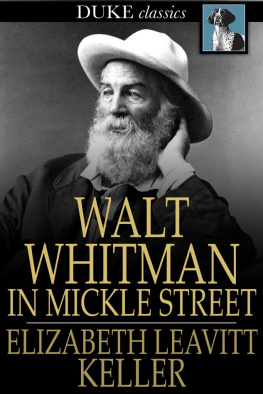

While Alans asthma improved, his marriage didnt. The third Chester was raised mostly by his heiress mother Myra, who was also an Eastern mystic and follower of the Omnipotent Oom, an early practitioner of yoga. Like his father, Chester III headed to Columbia University, but soon dropped out, got married, and was thrown in jail for his involvement with the Irish Republican Army. He also had an affair with the British poet Edward Carpenter (who had an affair with Walt Whitman); starred in a silent avant-grade movie, Borderline, with Paul Robeson; and began a utopian beach commune and a literary magazine on the dunes of San Luis Obispo, California. He changed his name to Gavin after his fraternal third great-grandfather.

During World War II, Gavin served in the US Navy.

But it wasnt until the 1950s and60s that his life really became interesting. Cut off from family funds, Gavin taught classes in San Quentin Prison, sold newspapers on the street, and prospected for gold. He began hanging out with the Beat Generation when he returned to New York City while attempting to write the Arthur family history. Pfaffs of Whitmans era was gone, but the dive bars Kettle of Fish and Caffe Reggio were there. Gavin was an early proponent of gay rights and was sought out by Alfred Kinsey for his study on gay sexuality.

Meanwhile, in 1962, Gavin published The Circle of Sex, which melded his concepts of astrology and human relationships into a kind of Wheel of Fortune that spelled out intimate meaning to its purveyors. Gavin Arthur was now a guru, mystic, and astrologist on the circuit doing talk shows, newspaper interviews, and book signings. There was always that family history he wanted to write in the back of his mind, but he never got around to doing it. It was fairly well known in some circles that President Arthurs papers were destroyed. Chester Arthur II led inquirers to believe that the former president didnt write much anyway. After his father died of a heart attack at age seventy-three in 1937, Gavin found about two thousand documents and eighty bound books of press clippings belonging to President Arthur in a bank vault in Colorado.

Gavin had a bit of his grandfather in him, because he did a pretty good job of organizing the papers and having handwritten letters retyped. In the late 1930s, some of those documents went to Columbia University and others to the New-York Historical Society. According to Reeves, the rest were moved to Gavins apartment in Manhattan and then back to the dunes of San Luis Obispo. Short of funds, he sold off portions of the papers over the next two decades to a mix of private collectors, various libraries, and the Library of Congress.

When Gavin Arthur died on April 28, 1972, he left all his family papers to the Library of Congress. They were stored in wooden fruit boxes in his apartment. Gavin broke the mold and was the last direct descendant of the Arthur Clan in America.

Precocious Nellie Arthur, whose antics delighted the presidential press, died young as her mother did. During surgery in 1915, she received a new procedure called a blood transfusion that didnt work. She was forty-three years old. Chester Arthurs town house on Lexington Avenue, where he fought for the Union and lived with his Confederate wife, operates as an eatery. On foggy mornings, his statue in nearby Madison Square Park appears to shed a tear for his long-lost Nell, while across the green Roscoe Conklings bronze likeness glares at his protg for eternity.